Many more men are dying on Australian roads than women. It’s time we addressed it

Men are killing themselves on the roads in large numbers. Currently, policymakers fail to recognise the different ways men and women use roads, and the resulting ways they are killed or injured.

The road toll is largely a male problem. In Australia in the 12 months to the end of October 2024, 1,295 people were killed on our roads, of whom 989 were male. Between January and September 2024, males were 81% of the drivers killed on the roads, but only 50% of the car passengers. Men were 96% of the motorcyclists and 90% of the cyclists killed on the roads.

Of the women who died in cars, only 52% were the driver (compared with 81% for men). The statistics for serious injuries on the roads are similar.

Even considering that men tend to drive more often and longer distances (and most cyclists and motorcyclists are men), these figures are startling. Here’s what contributes to this situation and how the roads can be made safer for everyone.

Different driving behaviour

The road fatality statistics do not show who was at fault in each case, but we should interpret them in conjunction with other research that shows men are more likely to speed, to drive under the influence of alcohol or drugs, and to not wear seatbelts. All these factors significantly contribute to deaths and injuries on the roads.

Women have high rates of distraction, such as texting or eating while driving, and have just as many minor injuries as men.

Men are less likely than women to wear a seatbelt while driving.

Shutterstock

The difference in men’s and women’s behaviours that cause injury or death highlight the need for different driver education campaigns.

Advertising companies have long understood the link between traditional masculinity, powerful cars and dangerous driving.

On the one hand, many road safety advertisements have specifically targeted men. A memorable example is the Australian advertising campaign that cast doubt on the penis size of men who speed.

On the other hand, advertising primarily sells cars to men, depicting cars in terms of power, virility, toughness and ability to protect one’s family.

Governments fund advertising campaigns that discourage men from speeding and drink driving, yet their policies that prioritise keeping traffic moving only reinforce the dominance of cars and speed in our society.

For example, the South Australian and federal governments are putting billions of dollars into a North–South Corridor to ensure cars and trucks move freely through Adelaide’s suburbs. The New South Wales government is putting at least $20 billion into Westconnex projects in Sydney.

We shouldn’t forget the large number of Australian children killed and injured on our roads. Policymakers’ choices to prioritise car use and speed affects children’s lives, including limiting their freedom of movement.

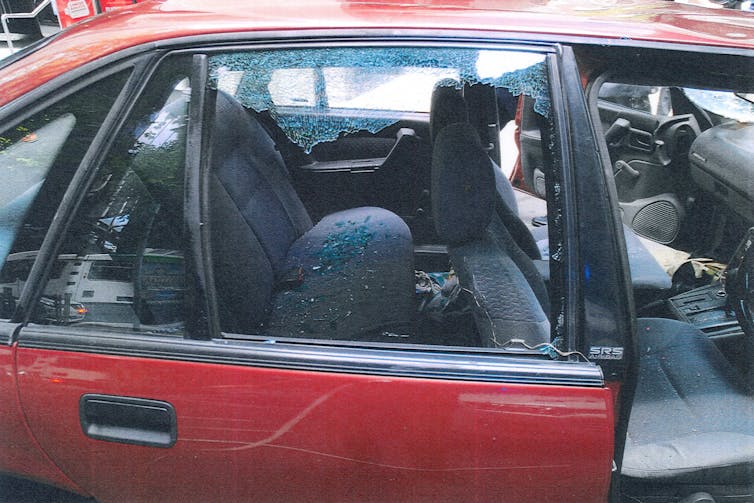

Cars as tools of violence

Men also use cars in deliberate acts of violence.

Men are involved in 78% of suicides (and suspected suicides) using vehicles on the roads in Australia.

But we also know cars are used in acts of domestic violence and coercive control.

For example, Hannah Clarke was burned to death with her children in her car by her estranged husband in 2020.

Other examples involve men deliberately running over their partners, although they are often charged with causing death by dangerous driving so the deliberate violence is under-reported.

Cars have also been used by men in notable cases of violence against peaceful protesters and of drug-affected men deliberately driving into pedestrians.

James Gargasoulas drove into pedestrians in Melbourne in 2017, killing six people.

DPP/AAP

Women’s fears about male violence more generally can also affect how they use transport. Many women do not catch public transport at night and some avoid walking because of safety concerns.

Yet women make up the majority of the poor.) and the elderly and are more reliant on public transport or walking.

The masculinity of motoring

All this is despite the fact that safety features such as seatbelts and airbags are designed for the average adult male body. Crash test dummies have traditionally been modelled on men. More research is needed with women’s bodies in mind to ensure women are equally protected when involved in an accident.

The love of large, fast cars is associated with our perceptions of masculinity. A lot of movies and car advertising encourage antisocial masculine behaviours, such as driving fast in powerful cars.

The traditional male dominance of the trucking industry and the masculine associations of large utes and four-wheel drives fuels this connection between masculinity, driving and speed (and sometimes drink driving).

State-supported car racing only entrenches these associations and encourages speeding.

In Australia, government policy fails to question this love of large, fast cars.

And it’s not just about keeping male drivers safe from themselves. Government policy also fails to prioritise the safety of children in car parks, the safety of women on public transport, or the right to mobility of older people or people with disability.

Australian governments could look to the example of some European cities such as Vienna, which has implemented a range of “gender-sensitive” city design ideas such as improving street lighting, prioritising pedestrians at traffic lights, adding seating, widening footpaths and removing barriers to using prams.

And they could look to Paris, which has lowered the city speed limit to 30km per hour to increase safety, benefit cyclists and respond to climate change.

It is time to acknowledge the associations between masculinity, power and speed are killing men and putting limits on the lives of women and children.

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of research assistant Kate Leeson in preparing this article.