Hundreds of cities have achieved zero road deaths in a year. Here’s how they did it

Matthew Mclaughlin

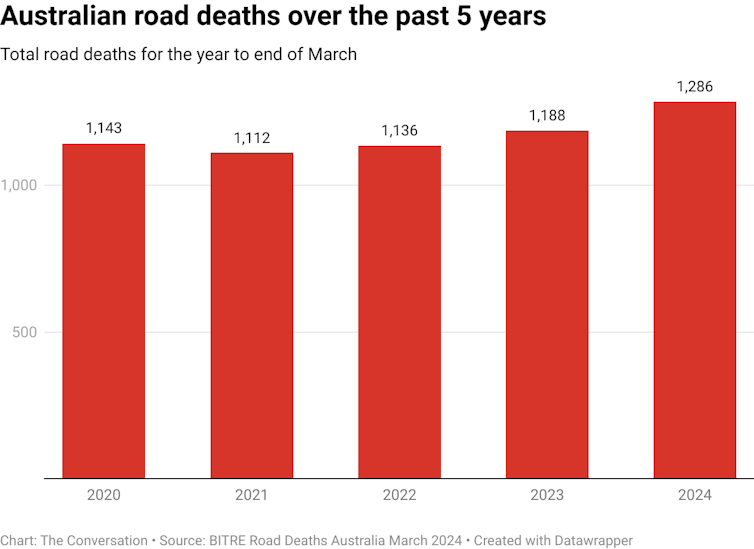

It’s National Road Safety Week and it comes on the back of a year in which 1,286 people died on Australian roads. The rising road toll – up 8.2% for the year to March – included 62 children. Tragically, road deaths remain the number one killer of children in Australia.

Road deaths are not inevitable. In 2022, at least 180 cities worldwide recorded zero road deaths. More than 500 cities with populations of more than 50,000 have achieved zero road deaths multiple times.

So cities can eliminate road deaths, or greatly reduce them. At the same time, these cities are creating healthier streetscapes that people want to be active and spend time on. They have done this by taking action on several fronts to make roads safe.

CC BY

Redirecting road funding

Walking and cycling infrastructure gets less than 2% of Australian transport funding. Reallocating funding from roads to walking and cycling, as for example France and Ireland have done, can increase road safety and reduce carbon emissions.

Australians want this shift in funding. Two-thirds of Australians support the idea that government should redirect road funding into walking and cycling infrastructure, according to a nationally representative survey by the Heart Foundation.

Reallocating street space

A disproportionate amount of road space is set aside for car travel and parking. For instance, across Melbourne’s busiest shopping strips footpaths are given 30% of the street space, on average, but account for almost 60% of all people using the street. Lanes for general traffic (cars, motorbikes and trucks) are also typically given around 30% of the space, but account for less than 20% of all people.

Similar results are found in cities elsewhere, from Budapest to Beijing.

Redesigning streets nudges people to drive at a safer speed. Before writing this article, we asked each other: “What would it look like if we designed our roads like footpaths, and our footpaths like roads?”

This question may seem unrealistic. But, as a design exercise, we wanted to explore what it could look like, to shine a light on footpath space.

We chose a random street, took a photo and set out to alter the image. We moved objects on the footpath – such as bins, signposts and mailboxes – to the edge of the roadway. Slightly more space was given for people walking, while still providing enough space for vehicles to operate safely within the roadway. Here’s this reimagination.

Across Paris, the Rues aux écoles initiative is reallocating street space on hundreds of “school streets” for children to play. The streets are designed to make it safe for children to play outside their school, for example, while waiting to be picked up.

Safer speed limits

The 100-plus-year experiment of cars on our streets is failing in Australia. But it’s not the cars per se, it’s the drivers speed that’s killing people. Speed and speeding are crucial factors in road safety. Australia’s 50km/h default speed limit in built-up areas is unsafe for many streets.

Globally, countries are adopting 30km/h speeds by default for side streets and urban centres, and it’s working. Reducing default speed limits to 30km/h reduces crashes, their severity and deaths.

Setting 30km/h as the default speed limit is a low-cost action that works to save lives. A majority of Australians support lower speed limits on neighbourhood streets. And, despite what drivers might fear, it has negligible impact on total journey times.

Lower speed limits make people feel safer, and that has a transformative impact. In Perth, for example, 2.8 million car trips a day are less than 5km – that’s two-thirds of all journeys. When people feel safe to walk, wheelchair or jump on their bikes for short journeys, such as popping out for milk or bread, they leave the car behind.

Swapping out these short car trips reduces congestion and carbon emissions. And it improves our health by boosting physical activity and mental well-being.

Where to start?

As researchers, we think it’s unacceptable to not act on the evidence of what works to boost road safety. We believe it’s time for urgent action. Here’s where to start:

zones around schools, especially reducing speed and more safe crossings

reallocating road funding and space to boost safety and efficiency

reducing speed limits in built-up areas by default.

Lower speed limits and redesigned streets should be backed up by public education campaigns and speed fines, to raise awareness of the deadly toll of speeding.

What can you do?

Be the change you want to see and become a champion of your local streets. When communities come together to call for change, it works.

Amsterdam, for example, wasn’t always a haven for walking and cycling. It took concerted community action against the high number of children dying on their roads.

Start a local group to champion safer and healthier streets in your neighbourhood. There are organisations to support you to take action, such as Better Streets.

![]()

Dr Matthew 'Tepi' Mclaughlin is a member of the Asia-Pacific Society for Physical Activity and the International Society for Physical Activity and Health. He is a Board Member of Better Streets and a member of the Active Transport Advisory Group of Westcycle. He has previously received research funding from the Australian government's Medical Research Future Fund and the government of Western Australia's Healthway. He also previously received salary support through the Australian Research Council's Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course.

Chris De Gruyter receives funding from the Australian Research Council. He is a Fellow of the Australian Institute of Traffic Planning and Management.