Can we cut road deaths to zero by 2050? Current trends say no. What’s going wrong?

Last year, 1,266 Australians died from road accidents involving at least one car and a driver, passenger, pedestrian or cyclist. The economic cost of Australian road trauma exceeds A$27 billion each year. That’s 1.8% of Australia’s GDP.

Australia has committed to an ambitious target of zero road deaths by 2050, known as Vision Zero. Originating in Sweden in the late 1990s, Vision Zero is based on a simple principle: no loss of life or serious injury on roads is acceptable.

But while we were making good progress at reducing road trauma, this has stalled in recent years, with Australian road deaths rising to levels not seen in nearly a decade.

If the current trend continues, meeting the Vision Zero target by 2050 appears impossible. So what’s going wrong?

Progress and setbacks

The journey towards reducing road trauma has had both progress and setbacks. In the early 1990s, roads were claiming more than 2,000 lives in Australia each year.

Over the years, we managed to significantly reduce this number. By 2020, the annual road toll had dropped to around 1,097, almost halving the figure from three decades prior.

Read more:

Are Australia’s roads becoming more dangerous? Here’s what the data says

However, recently, we’ve witnessed a worrying reversal: three consecutive years of increasing road deaths.

In 2023, 1,266 people died in Australian road accidents.

Australian Road Deaths Database

With more progress, it gets harder to improve

Over the years, through various safety initiatives and public awareness campaigns, we managed to significantly reduce road trauma. This includes measures such as seatbelt, helmet and child-seat laws, as well as regulations around speeding, drink-driving and phone use.

Read more:

Going on a road trip this summer? 4 reasons why you might end up speeding, according to psychology

We also have safer cars and infrastructure now. Modern car features and technologies – such as auto-emergency braking, lane-keep assist, blind spot monitoring and airbags – are associated with a lower risk of road accidents and fatalities.

With the significant benefits we have gained from these measures, additional safety measures will naturally lead to smaller improvements. But the toll is actually worsening.

What role did the pandemic play?

For the first time in decades, we’ve seen a sustained increase in road deaths in Australia and other countries such as the United States.

During the pandemic, more people bought cars, perhaps to avoid public transport.

However, this alone doesn’t fully explain the rise in road deaths. With more people working from home, there has been a reduction in daily commutes. Plus, the increase in the number of vehicles has been modest relative to the rise in road deaths.

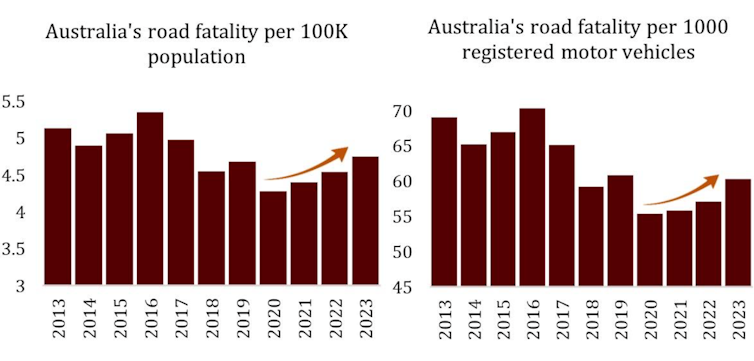

This shows the number of road deaths in Australia normalised by the population size (left) and the number of registered vehicles (right).

Australian Road Deaths Database

So the assumption that more people are dying because there are more cars is, at best, a partial explanation.

Risky driving behaviours

The post-pandemic data shows several indicators of declining road user behaviour and attitudes.

In New South Wales, for example, there has been a substantial increase in fines for minor speeding offences.

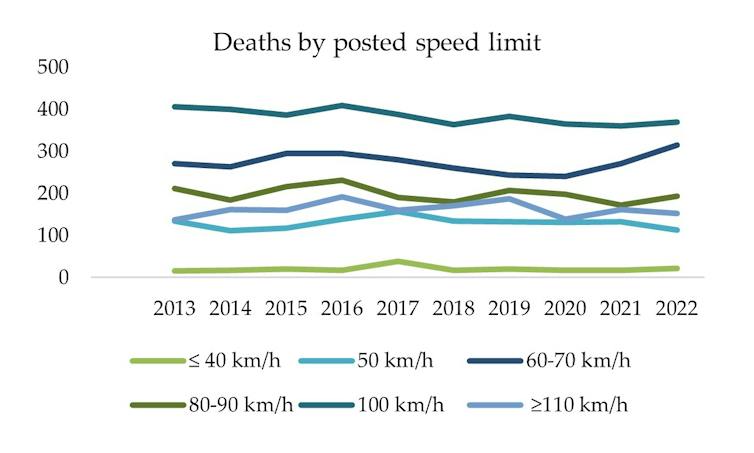

Across Australia, the number of fatal crashes in 60–70 km/h zones has been rising, from 241 associated deaths in 2020 to 315 in 2022. Speeding is likely to play a role, but it’s unclear to what extent.

This shows the number of road deaths in different speed limit areas.

Australian Road Deaths Database

Read more:

How to never get a speeding fine again — and maybe save a child’s life

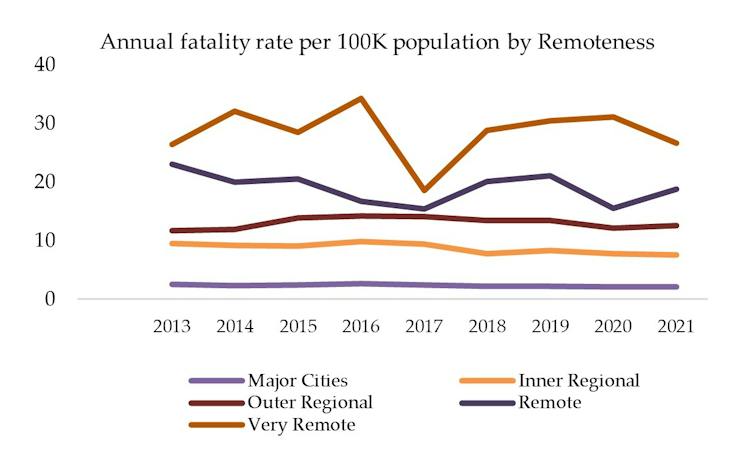

Remote and regional roads still pose a significantly higher risk of death, relative to their population. The road death risk is about six times higher in outer regional areas and nine times higher in remote areas compared to major cities.

This could be due to a number of factors: speeding, risk-taking behaviours and others such as poorer infrastructure, lower levels of enforcement, collisions with wildlife, long-trips and driver fatigue.

This shows the relative risk of death, based on the remoteness of the road.

Australian Road Deaths Database

Deadly crashes involving drivers without valid licences have also risen. In 2019, 96 deaths were reported in crashes involving operators without a valid licence. This rose to 116 in 2020 and 128 in 2021.

The number of road deaths involving a cyclist or motorcyclist not wearing a helmet was 19 in 2019, but it jumped to 28 in 2020 and 2021, a 47% increase.

The proportion of road deaths with drugs detected in the operator’s system has been rising, from 14% for drivers and 11% for motorcyclists in 2015. In 2021, these numbers rose to 17% for drivers and 28% for motorcyclists.

Another worrying trend is the increased risk of road death for the 17–25 age group. This age group is now at the highest risk of fatality on our roads, surpassing the over-75 age group.

Too many young people are dying in road accidents.

Rusty Toadro/Shutterstock

Improving road safety

For the foreseeable future, human drivers will continue to be the primary operators of vehicles, and human factors remain the biggest contributor to road trauma.

When it comes to saving lives on the roads, we need to monitor attitudes to road safety. One way is through regular surveys at state and national levels, tracking scores of behavioural indicators over time. Much like political parties using ongoing polls to track the political climate, regular tracking of the community road safety climate allows us to proactively address challenges emerging from user behaviour, rather than waiting for alarming statistics.

Australia has some of the most progressive road safety policies globally. But our ambitious targets demands focusing more on user behaviour. Road safety campaigns, delivered via TV and other media, can influence road safety behaviours, with tailored campaigns targeting the specific demographics and behaviours of concern. Intensifying investment in these campaigns could be a key strategy in achieving our road safety goals.