Why are Canadian schools so vulnerable to cyberattacks?

Meanwhile, the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ federation confirmed this month that a ransomware attack struck them in late May. The incident involved an “unauthorized third party” that gained access to and encrypted its systems, though the union said there was “no evidence” their data had been misused.

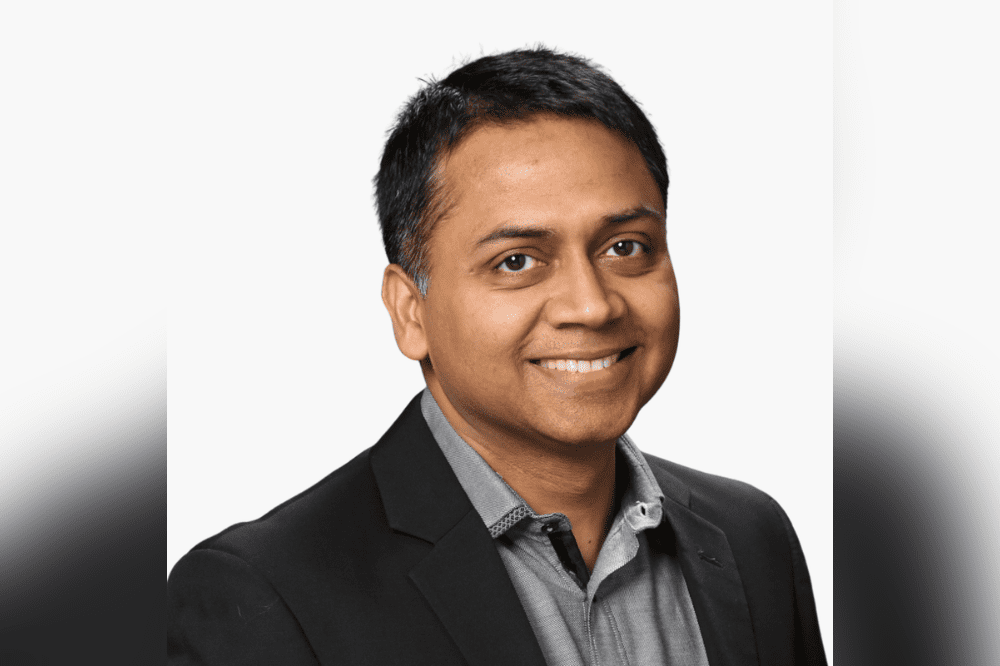

“The problem with the education sector is there’s a much bigger attack surface,” explained Rajeev Gupta (pictured), co-founder and chief product officer at Cowbell, a leading cyber insurance provider for small and medium-sized enterprises. The Pleasanton, California-based firm has offices across the US and in Toronto and London.

“[Public schools] tend to have older versions of the software running and don’t upgrade systems regularly. They don’t have the hygiene to stop using end-of life-software, for example,” Gupta continued.

Why are schools so vulnerable to cyberattacks?

The lack of robust cybersecurity measures stems from underfunding within schools and educational groups. Often, they don’t have enough resources or budget to invest in cybersecurity or train staff and students to practice good cyber habits.

According to Gupta, these organizations are notorious for not having appropriate network segmentation (which breaks larger networks into smaller pieces or sub-networks to limit access privileges and protect the network from widespread cyberattacks).

“There’s a lot of different departments in schools, with every department doing their own thing with their respective software systems, and these networks tend to be connected. If the bad guy gets in, it’s very easy to gain lateral movement within the school system,” Gupta said.

Schools often run clubs and labs where students get more privileged access to the network. But without network segmentation, cyber threat actors can quickly gain a foothold in the network to carry out their attacks.

“If you add those things together, you’ll see why there is a higher tendency for schools to get attacked,” Gupta observed. “At the same time, schools sit on a wealth of PII [personally identifiable information] data. There’s a lot of stored information on students, teachers, and parents that bad guys are after.”

In the past, malicious actors targeted specific companies or enterprises with cyberattacks. But the threat landscape has changed, with groups now less discerning about who or what they hack, making small and medium-sized enterprises especially vulnerable.

“Nowadays, it’s more about going for the lowest hanging fruit,” Gupta told Insurance Business. “Bad actors scan the internet, look for resources, open ports, and whatnot, and they get in. Only then do they see it’s a school. They’re not specifically going after [the school]. It’s just that the school has much poorer cyber hygiene.”

What can the education sector do to protect itself from cyberattacks?

Ransomware and business email compromises are the most common cyber schemes that the education sector suffers from, according to Gupta. But the good news is that both types of attacks can be prevented with training, and schools are the best environments to provide cyber education.

“Making sure that the teachers and students are educated on cyber risks is one of the best practices,” the cyber insurance leader said.

“Schools should introduce cybersecurity awareness training to students early because that knowledge can help them throughout their life. You must ensure they understand the importance of password strength, multi-factor authentication, not clicking on phishing links, etc.”

Schools and teachers’ groups can also take simple steps like applying regular software patches, enabling automated software updates where possible, and installing antivirus software on all systems.

“I also think internal systems should not be accessible without individuals going through a VPN [encrypted network connection] protected by multi-factor authentication,” Gupta advised.

“Make sure nobody from the internet can access all the internal administrative systems with just a username and password log-in. That is just havoc waiting to happen.”

Creating an incident response plan and enacting tabletop exercises also help prepare schools for the uncertain future. Just as schools do drills for fire and flood, a cyberattack drill can help staff and students understand how to reach out and whom to reach out to when a breach occurs.

Finally, cyber insurance policies are a good risk transfer option for schools, allowing them to access the resources they need to shore up their cybersecurity measures.

For Gupta, even small, incremental investments in cybersecurity and better cyber hygiene can protect educational organizations and schools.

“It’s like the 80-20 rule,” he said. “You put in 20% effort [into cybersecurity], and you get 80% of the benefit.”

How else can the education sector manage its cyber risks? Leave your thoughts in the comments below.