Oil Spill Prevention and Response – What companies need to know about their regulatory requirements

Authored by Gregg Shields, Risk Consulting Manager, Environmental, AXA XL

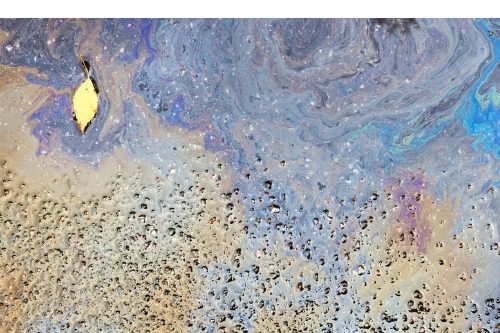

In 1989, one of the biggest environmental disasters in U.S. history occurred off the shores of Alaska when the oil tanker Exxon Valdez ran aground, leaking 11 million gallons of oil into Prince William Sound. Hundreds of thousands of animals were killed, and the ecosystem has yet to fully recover 25 years later. Exxon ultimately paid roughly $1.25 billion in settlements.

This incident, along with a handful of other catastrophic spills in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, spurred new regulatory scrutiny of organizations that use, store, manage or distribute large quantities of oil. Specifically, the USEPA introduced the requirement of a Facility Response Plan (FRP) in addition to existing Spill Prevention, Control and Countermeasure (SPCC) Plans. Together, these plans ensure that organizations are prepared to prevent and mitigate the most devastating consequences of oil spills.

Benefits of a robust plan

A strong oil spill prevention and response plan has multiple benefits. First and foremost is the mitigation of environmental damage and risks posed to nearby communities, including both bodily injury and property damage risks. Second is preventing the loss of the product itself, which can result in significant business interruption impacts. Third is the avoidance of costs associated with containment and remediation, which can easily reach into the millions or, as the Exxon Valdez incident proved, billions.

Who needs an SPCC Plan vs. an FRP?

Organizations that meet the following criteria are required to have an SPCC Plan:

Engage in non-transportation related operations (transportation companies are regulated by the U.S. Department of Transportation);Store more than 1,320 gallons of oil above ground, or more than 42,000 gallons underground; andCould reasonably discharge oil to navigable water – broadly defined as any waters or adjacent wetlands – in quantities harmful to the environment.

Only a subset of companies that tick these boxes will also need to prepare an FRP. This requirement applies to any facility that meets the above criteria, and from which a spill would cause “substantial harm.” The USEPA defines facilities with the potential to cause substantial harm as those that:

Store > 42,000 gallons of oil and transfers it over water, ORHave more than 1 million gallons of oil storage capacity that either does not have sufficient secondary storage for above ground tanks, is located near a sensitive environment where a spill would cause injury to wildlife or force a shutdown of drinking water access or has had a reportable spill of more than 100 gallons within the past 5 years.

Note companies that manage certain quantities of hazardous substances (other than oil) should also review the applicability of new USEPA FRP requirements in 40 CFR 118 finalized earlier this year.

Any oil-handling personnel should be trained not just on general regulatory requirements, but on the facility’s specific SPCC or FRP protocols. They should be knowledgeable about any equipment and related inspection/deployment procedures used in the detection or containment of a spill.

What is the difference between an SPCC Plan and an FRP?

As their names suggest, SPCC Plans focus on both preventative and mitigation efforts, while FRPs focus additional resources on response.

All SPCC Plans are required to include some core elements. Facilities must include a diagram and description of their site, information on their storage tanks and how often they are inspected and tested, descriptions of any equipment used to load, unload or transfer oil, how personnel are trained, and how often all of these factors are reviewed and improved when deficiencies are found.

Plans must also be certified by a professional engineer, or in some cases, self-certified by the facility owner/operator every 5 years.

FRPs include some additional pieces such as hazard analysis, descriptions of worst-case spill scenarios, spill detection procedures, and a detailed emergency action plan that includes information about response equipment and personnel to be notified. Both plans should detail inspection procedures and site security protocols and procedures.

Both SPCC Plans and FRPs require facilities to have spill response plans with clearly defined spill reporting criteria. For example, the SPCC rule states that any spill – even as little as 1 gallon – requires reporting to local or state regulatory agencies. If that spill reaches navigable water, it must also be reported to the National Response Center or a regional USEPA office. This contact information should all be easy to find within the plan. Additional contact information for any contracted spill response firms or local spill response consortium resources should also be readily available.

The importance of training

Training is a critical component of oil spill prevention, containment and mitigation, so much so that the USEPA’s Oil Pollution Prevention regulations include specific requirements around training.

Any oil-handling personnel should be trained not just on general regulatory requirements, but on the facility’s specific SPCC or FRP protocols. They should be knowledgeable about any equipment and related inspection/deployment procedures used in the detection or containment of a spill. Facility management should conduct briefings with all staff members at least annually to review the SPCC Plan, discuss any known discharges or lessons learned, and update team members on any new precautions being implemented.

A key element for effective implementation of any environmental protection program is relevant training on facility staff responsibilities. Drills and table-top exercises are best practices to ensure all parties get a hands-on run-through before an incident occurs.

The final piece – an insurance policy

All of the planning and training in the world can’t prevent every accident, and spills will inevitably still occur. Every organization that handles oil or other hazardous substances should have a pollution liability policy to recover from the expenses of cleanup, legal fees, regulatory penalties, and any third-party liabilities.

To learn more, download our most recent Environmental white paper on Spill Prevention, Control, and Countermeasure (SPCC) Plans & Facility Response Plans (FRPs) click HERE