Whole Life Insurance Scam — Why I Fell for It – White Coat Investor

[Editor’s Note: There are plenty of reasons why a physician would want to become a paid survey-taker. You can make extra money, start a solo 401(k), and use your medical knowledge to impact new products. Best of all, it’s easy to get started! WCI has five recommendations for survey companies who want to work with you. Sign up today and use a little bit of your downtime to make extra cash.]

By Dr. Rikki Racela, WCI Columnist

I have written previously of how being duped into purchasing whole life insurance torpedoed the financial lives of my wife and me, dual-income physicians who ended up in $31,000 dollars of credit card debt over seven years because of this financially deadly product. I am not alone as hundreds of doctors have documented their woes on one of the, if not the, longest WCI forum threads. It is hard to believe how phenomenally intelligent doctors could be financially illiterate, but it is even much more unfathomable to learn how many doctors like myself were fooled into buying the worst money-sucking financial investment product in the industry.

How does this happen? In short, our brains make us do it!

First off, a disclaimer.

Before I go on, I want to encourage those readers who were smart enough not to be duped, unlike me, to continue reading. The following will outline not only how doctors and high-income professionals make the mistake of a whole life purchase, but how they make bad financial decisions in general. It will also help you convince other doctors to get out of their whole life insurance policies. After becoming financially literate, I found out that one of my own colleagues in my group also purchased this terrible product. You probably know tons of colleagues who have been suckered, and this will help them get out of a whole life policy and repair their financial lives.

How the Financial Industry Uses Our Own Brains Against Us

In reality, our brains don’t make us buy whole life. Instead, the financial industry insidiously uses ingrained human behavior to its profit and our loss. Make no mistake, the insurance industry that tricks us into buying whole life knows more human psychology and neurology than any doctor, including myself as a neurologist. How is this possible? As doctors, we utilize our knowledge of the human brain and psychology to help our patients. The insurance industry wields that same knowledge for pure profit. It has perfected the art of using behavioral biases and heuristics to get you to sign on the dotted line. What are these biases and heuristics? From my experience of being screwed, these include familiarity bias, confirmation bias, myopic loss aversion, mental accounting, bundling, the halo effect, anchoring, sunk cost fallacy, status quo bias, and framing. Whew, no wonder I got taken! Let’s dive in.

Familiarity Bias

It turned out the deliverer of my financial doom was a close friend of mine touting himself as a financial “advisor.” Unfortunately, he was a salesman, but I had grown up with the guy playing Little League and high school football together in the same town. There was a familiarity bias where I felt safe and comfortable choosing him to manage my money and taking his direction. As Jason Zweig writes in his book Your Money and Your Brain, familiarity bias helped early humans survive:

“If our early ancestors had not learned to steer clear of the germs, predators, and other dangers lurking outside their own bodies and beyond their immediate home ground, they would not have survived. Too much curiosity could kill the cave dweller. Over the course of countless generations, a preference for the familiar and a wariness toward the unknown were ingrained into the human instinct for survival. Familiarity became synonymous with safety.”

My buddy was familiar to me so I trusted him. Financial “advisors” are, after all, people, too. Because of familiarity bias, they are seen by potential marks as friends, teammates, brothers, cousins, etc. And the insurance industry knows this familiarity bias exceedingly well. Companies teach their salesforce to hit up family and friends so they can sell whole life insurance. Because of familiarity bias, our defenses are down, and we put the BS meter away. This is exactly how Bernie Madoff scammed victims out of billions.

A 2010 Forbes article written by finance professors Li Huang and J. Keith Murnighan had this to say about Bernie:

“Our research suggests that Madoff may have deliberately or inadvertently taken advantage of the automatic trust process regardless of whether his family members and business associates were victims or confederates. Even if he didn’t seem trustworthy, the fact that his closest relatives and associates invested with him could have provided a subtle, non-conscious signal that he was actually trustworthy. After all, foxes never prey near their dens, and thieves only steal far from their homes.”

And it was this familiarity bias that resulted in my buddy preying on me with the sharp, dirty teeth of whole life insurance policies sinking into my financial skin.

Is Whole Life Insurance a Good Investment? Seeking Confirmation Bias.

Despite only having read Dr. Jim Dahle’s book in December 2018, I had years earlier encountered his work on a website called QuantiaMD, where doctors were paid to produce video lectures regarding various physician-related topics. As part of one of those lectures, Jim had explained that whole life insurance was not a very good investment. He said it was meant to be sold, not bought; that it would be a hindrance to building wealth; and that it only enriches the “advisor” selling the product.

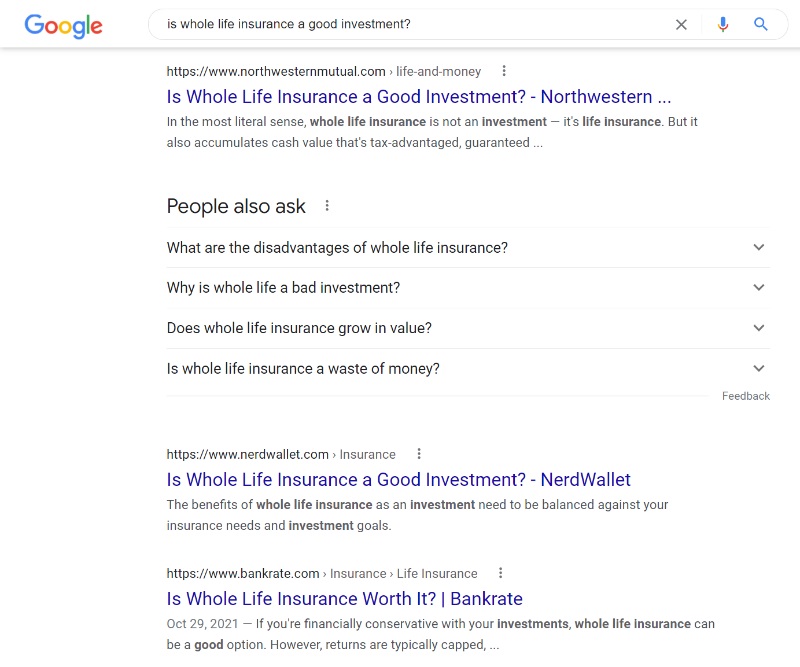

Whoa!!! Wait a minute!!! After seeing this lecture, my mind was blown, and immediately I googled the following: “Is whole life insurance a good investment?”

I don’t exactly remember what popped up, but when you google this now, you get this as your first hit:

I do remember that in 2016, when I googled this question, a similar statement popped up, “confirming” that whole life insurance was a good idea (as you can see in the words bolded in the above screenshot), and I disregarded Jim’s sage advice. Hence, I fell victim to confirmation bias, where you seek out information that confirms that you did not make a mistake while disregarding any information to the contrary.

Shockingly, the mere act of me initially approving whole life insurance as a good idea solidified my accepting future information supporting it, while disregarding dissenting information. Amazing how our brains are wired! Forget the movie Inception where Leonardo DiCaprio had to infiltrate a guy’s brain while asleep to plant a thought. I should have taught Leonardo DiCaprio about confirmation bias! Or better yet, the insurance companies should have taught Leo what they teach their whole life insurance sales force.

What I should have done to combat confirmation bias was google this question next: “Is whole life insurance a bad investment?”

What pops up nowadays is:

It turns out one of the best ways to fight confirmation bias is to ask the question in a different way. Should have done that years ago.

Myopic Loss Aversion

I happened to be duped into buying whole life in the summer of 2012, only a few years past the Great Recession. This recent nosedive of equity and real estate markets was used as ammunition to sell whole life. My buddy scared me with how bad the recession was—how it was the worst market crash since the Great Depression—and that the cash value within whole life insurance is shielded from such tragedies. Unbeknownst to me then but clear as day now, he was using the behavioral bias of myopic loss aversion. This behavioral bias is when people and potential financial whales like doctors focus on the short term, leading to an overreaction of negative events (the recession in my case) at the expense of doing things that would benefit in the long term (like paying down student debt or buying equities at discount prices). Pretty slick!

Mental Accounting

Another sort of crafty behavioral bias my supposed “advisor” used to fool me was utilizing mental accounting when describing the cash value portion of the whole life policy. This part of the policy would be earmarked for retirement, a worthy goal where he reinforced to me time and time again that most Americans do not save for retirement. Here comes whole life insurance to save the day!

However, at the time I purchased the policy, I still had medical school debt which I could have paid off. But because of mental accounting, the money I was throwing away at the whole life policy was supposedly building my retirement nest egg. I had placed a different value of the whole life premiums vs. making student loan payments under the deceptive guidance of my salesman. Man, I thought, I can’t touch the part of my budget going to whole life insurance since it’s earmarked for retirement. I didn’t realize I was being played.

The mental accounting bias can be fought by remembering that money is fungible, and in my circumstance, paying whole life premiums and building cash value was taking away from making me debt-free. I should have looked at the money I was throwing away on life insurance premiums as part of an overall financial plan. I should have evaluated those dollars and should have placed them where they built the most wealth. Mental accounting prevented me from realizing that paying $28,000 of whole life premiums was not making the greatest return on my money. Turns out, after seven years, I had paid $170,000 of whole life premiums for my wife and me. I could have paid off our student debt that was around 3% interest and locked a guaranteed rate of return of 3%. My return on my whole life insurance policies? Well, I lost $50,000, as my cash value for the whole life policies were $53,000 and $67,000, respectively. You can do that math, but it’s not that hard to calculate that whole life set me way back.

Currently, I have a little less than $100,000 of student debt left. Yes, my wife and I could have been debt-free by now.

‘Benefits’ of Bundling Insurance

Oh man, this is a whole life insurance salesman’s signature selling point: that it is the all-in-one bundled solution for all your financial needs. From buying a home (my buddy told me you could borrow against the cash value) to paying for college (borrow again from cash value when the kiddos are college age) to funding retirement (can again borrow against cash value) to leaving a legacy (I was sold a $1 million death benefit), whole life insurance is sold as being the only financial play that meets all your financial goals.

But as Jim Dahle points out, whole life insurance does not help one accomplish any financial goal particularly well, and there are many other vehicles that are cheaper and more beneficial to accomplish these goals. It’s just like buying the Verizon Triple Play because it’s cheaper bundled together even though I never use the landline. I bought whole life because my buddy said it could enable me to accomplish multiple financial goals in a single solution. The bundling bias made me reflexively think I was getting great value.

The Halo Effect

Did I mention that my salesman was a Certified Financial Planner? Yes, despite being an insurance salesman, he had the CFP designation, one that according to the CFP website states:

“CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ certification is the standard of excellence in financial planning. CFP® professionals meet rigorous education, training and ethical standards, and are committed to serving their clients’ best interests today to prepare them for a more secure tomorrow.”

In 2012, when I made the damaging financial decision to buy whole life, I did have the foresight to verify the significance of my salesman’s credentials, including the CFP designation, and I was told that he had my best interest at heart. However, the CFP credential unfortunately can act as beautiful sheep’s clothing for greedy wolves. I mistook the CFP board as similar to our medical boards—as doctors, if we violate the MD/DO standards of care, we lose our license. This led me to blindly and faithfully sign on the dotted line to purchase whole life, thinking that if my best interests were violated, my buddy would lose his CFP designation. The CFP gave my buddy the “halo effect.” Just like when the picture of a beautiful person makes us automatically assume they are a good person, just having a CFP made me feel my buddy would be a fiduciary and automatically have my best interest in mind.

Alas, the CFP is more a knowledge-type degree, just like getting a college degree in religion does not obligate you to be religious at all. Allan Roth, author of How a Second Grader Beats Wallstreet and a previous WCI podcast guest, wrote an article about how the CFP board has given up in trying to protect the public from abuse of the CFP designation. Insurance companies recognize this halo effect all too well and hire CFPs all the time to fool people like myself into a false sense of security. A CFP is incredibly not required to be a fiduciary ALL the time but instead can be fiduciary one minute and sell you a whole life policy in the next, meeting a different standard called the suitability standard. It is ridiculous how the insurance industry can get away with this, but that is how the law stands now, making the halo effect a continued and effective weapon when harpooning whales like me with whole life policies.

Anchoring

I remember when I was first shown material for purchasing whole life insurance, I was first presented with the illustration. A whole life illustration demonstrates how much cash value one can accrue each year until one reaches old age. And man, those numbers were high! Looking back at the illustration, by age 65 I would have paid $371,930 in total premiums, and if I let the cash value ride, it would have grown to $1,487,045 by age 77. Of course, when I was being sold the policy, my buddy emphasized this number before pitching me anything else. What he was doing was anchoring me to the huge number. I believe he did mention the asterisk right next to this number later on in his pitch, glossing over quickly that this amount is not absolutely guaranteed and would need paid-up additions and continued reinvestment of dividends and for the insurance company to continue to be profitable, and on and on and on.

It didn’t matter what else he said; I was already anchored to the humongous amount he mentioned first. He anchored me to the highest number on the illustration page, and that was what stood out in my brain for the rest of his sales pitch. Due to anchoring bias, as I signed on the dotted line, all I kept thinking about was the $1.5 million.

Sunk Cost Fallacy

Even as I was getting to be financially literate, I was tempted to keep paying into whole life premiums and just let this financial mistake ride because of this next bias. The sunk cost fallacy is when you keep throwing more money in after bad. One example would be government projects where, after throwing billions of dollars in a project that turns out to be getting too expensive, the government decides to keep throwing in more money. As the thinking goes, “Well, we paid so much into it, we can’t quit now.” Another famous example would be if you bought very expensive tickets to a concert, but on the night of the concert, there was a huge blizzard. Now you will have to risk dying in an ice storm just to make the pricey concert. What do most humans tend to do? Risk the immense cost of losing your life, go out into the ice storm, and attend the concert.

This is the sunk cost fallacy. In terms of whole life, I could have said, “Well, I spent so much money on whole life, and eventually it will come out positive sometime in the future. Might as well keep paying.” I was tempted to go down this route as the sunk cost fallacy is part and parcel to loss aversion. If the government doesn’t see that expensive project through, then it just wasted whatever it spent so far. If you don’t go through that deadly blizzard to attend the concert, then you are out the cost of those tickets. And if I didn’t keep paying into whole life, then I am acknowledging that I was stupid and lost $50,000.

Status Quo Bias

This was another bias that tempted me to stay in my policy. My salesman had mentioned there were so many other options for investing—from stocks, bonds, commodities, annuities, mortgage-backed securities, real estate, lions and tigers and bears oh my! And so on and so forth. His explanation of the financial world made me vertiginous, and this was on purpose. He, as well as the entire financial industry, is trained to present finance as intimidating and infinitely confusing, even for a doctor. They are playing to the human brain’s status quo bias, that when presented with many complex and confusing options, the bias is to stay in whatever investment you are in. It is related to the paradox of choice, where if presented with too many choices, we end up having analysis paralysis and not making any choice at all. My buddy was making the financial world intimidating and scary, tempting me to stay in my whole life policies.

Framing

Oh man, this one really got me. As my “advisor” was pitching whole life insurance, not once did he ever say I was “purchasing” anything. He explained that the death benefit would be the greatest financial “gift” to my future children and that the premiums I would pay would be an “investment.” What better gift to give your children—your seed and future, those cute kids—in the event of a terrible tragedy of your passing than to bequeath them $1 million? Or that even if I didn’t kick the bucket, the cash value was an “investment” for whatever my financial goals could be in the future. That is exactly how my buddy framed it. I wasn’t buying a whole life policy—I was giving the best gift you could give to your children! I was showing how much I loved them through buying this policy. And even if I didn’t die, I was “investing” through the accumulation of cash value, taking a major leap forward in accomplishing my financial goals. Of course I signed.

Fighting Fire with Fire: Reframing

Despite all the above human biases at financial companies’ disposal, how did my wife and I manage to fight these embedded psychological tendencies used against us? We used our own personal and painful experience with whole life insurance against the insurance companies. We used the framing heuristic to bestow on us the strength to fight whole life and to go down the path of financial literacy. We fought fire with fire.

Seven years after my purchase of our whole life policies from the buddy who, by the way, I no longer talk to, I was attending my 3-year-old son’s Little Gym Olympics. The Little Gym is a chain of gyms teaching gymnastics to infants and toddlers. My son had completed the season, and there was a mini-celebration. No big deal, unless it is YOUR child in their first Little Gym Olympics. Luckily I was there, but guess who couldn’t come because she had to take extra call to keep up with paying $28,000 of yearly whole life insurance premiums? Mommy, my wife, a dedicated anesthesiologist, was in the hospital putting in epidurals on the Valley Hospital OB floor at the same time as our son’s event. I sent her pictures. She told me she cried when she saw them—luckily pregnant women’s backs are turned while they’re receiving epidurals so they didn’t see her tears.

How is that for a frame? My wife will never get that time back. Whole life took that away from her. At the same time, while our time from our children was stolen from us, we were enriching insurance company CEOs to lavishly have time to hang out with their own children. One article cited MassMutual’s CEO making as much as $18 million! (FYI, it was not MassMutual who sold me the policy, but an even more infamous doctor financial killer insurance company.)

If any readers are pitched whole life, remember this story. Or if you know somebody who got hoodwinked, relay this story so they get out of their detrimental whole life policy. Frame whole life insurance this way. Tell them how whole life caused a hard-working doctor to miss her son’s Little Gym Olympics, while at the same time funding a financial CEO’s opulent eight-figure lifestyle. My wife will never get that moment back. Thanks, whole life insurance!

We moan as doctors how it is our busy careers that prevent us from spending time with our families. But for my wife and me, it was whole life insurance. You know what my wife does now? Instead of paying $28,000 in annual whole life premiums, we make the financially intelligent and family-oriented decision of paying $1,500 to a colleague in her group to take call. That’s almost 20 moments a year where, instead of throwing money down the whole life sewer, she gets to attend a Little Gym Olympics, a Little League game, or a dance recital. Whole life insurance was taking her kids away. Getting the heck out of our painful whole life policies and becoming financially literate brought her children back.

Jim Dahle has already cogently written how whole life insurance is not an investment but a product to be sold, using a rational and thoughtful framework of the facts. I hope that the above has combated the emotional and irrational heuristics that might have duped you or other high-income professionals into buying whole life. If you have already been sold poison, maybe it will emancipate you from continually paying damaging premiums at the expense of building wealth. Just like my friend convinced me into buying whole life, utilizing my own brain with its biases and framing the vivid imagery of my kids’ future, you can use my story (well, technically my wife’s) of how she missed our son’s Little Gym Olympics.

Maybe it doesn’t seem rational to use some random stranger’s story of missing some random kid’s event, but neither does buying whole life. Many of our other poor financial decisions don’t seem rational either. And I just threw a little familiarity bias in there because my wife, just like you, is a doctor and has bled the same blood and has been in the trenches of residency training just like all of us. Just like financial companies use our emotional, reflexive brains against us, I hope you will join us as we spread our painful lesson of buying whole life, and use it as a frame to protect against Wall Street predators to never buy whole life insurance or other hurtful financial products ever again.

Do you have questions about life insurance and what kind of (non-whole life) policies would be the best for you? Hire a WCI-vetted professional to help you sort it out.

What do you think? Have you been pitched whole life or some other unhelpful financial product using the above behavioral biases against you? Do you think you can use behavioral biases to your advantage to protect yourself and others from these financial products and become more financially literate? Comment below.