Biden Administration Softens Final Health Regulations

What You Need to Know

The group that wrote the regulations includes the IRS and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as well as the Labor Department

In July, the drafting team suggested it could make big changes to fixed indemnity coverage rules.

Today, the team said it might still make big changes, someday. But not right now.

The U.S. Department of Labor is part of a three-department Biden administration team that today backed off from the tougher provisions included in draft health insurance regulations released in July.

The final version of the regulations, which is set to appear in the Federal Register April 3, would cap the maximum duration of a short-term health insurance policy from one corporate family to four months.

The final version would also add tougher notice requirements for short-term health insurance policies and “fixed indemnity” health insurance policies, or policies that pay a set amount of cash when people get sick, suffer injuries or go to the hospital.

The departments suggested that they could come back and add tougher regulations later.

But the final regulations would continue to allow the sale of both short-term health insurance and fixed indemnity coverage, would not impose any new marketing rules; and would not change the benefit design or underwriting rules. Healthy clients who want to try to cut premium costs by using short-term health insurance as their main medical coverage could simply line up short-term coverage from a different corporate family every four months.

What it means: Biden administration agencies may be open to ending or slowing some formidable regulation-writing efforts.

The team: In addition to the Labor Department’s Employee Benefits Security Administration, the team includes the U.S. Treasury Department’s Internal Revenue Service and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The products: Short-term health insurance — a product officially described in the regulations as “short-term, limited-duration insurance” — is a product that traditionally has provided temporary coverage for people who are between jobs or in a tryout period at a new job and have no access to employer-sponsored health coverage.

The fixed indemnity product category includes products that pay fixed amounts when people have health problems.

That category could also include critical illness insurance, cancer insurance and other products that pay benefits when people suffer specified illnesses or injuries, but the regulation-writing team decided to keep that out of the new final regulations.

About 236,000 people had short-term health insurance in 2022, and as many as 8.1 million people could have individual or group fixed indemnity coverage, depending on the definitions used, according to National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ data and America’s Health Insurance Plans survey data cited by the regulation writers.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and the Affordable Care Act package of 2010 have excluded, or “excepted,” short-term health insurance, fixed indemnity products and some other products from the federal rules that apply to major medical coverage, such as the federal ban on medical underwriting, Federal agencies have typically left regulation of those products to state insurance departments, and the rules for the products vary widely from state to state.

While President Barack Obama was in office, federal agencies tried to tighten excepted benefits product rules.

When Donald Trump became president, agencies loosened the rules.

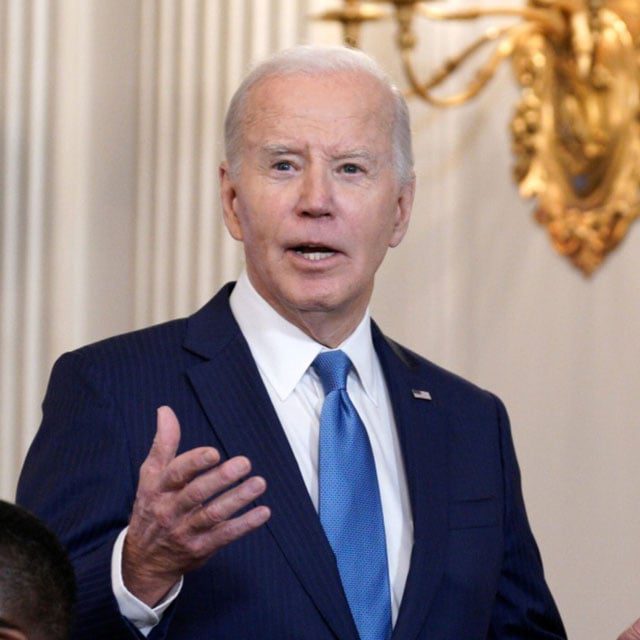

Under President Joe Biden, the pendulum has swung back toward tightening.

The departments’ thinking: Department officials argue that they need to act because short-term health insurance and fixed indemnity fail to provide the benefits and consumer protection rules that the ACA provides; sellers often confuse consumers into thinking they are getting major medical insurance; and the products lure younger, healthier people away from the individual major medical policies sold through the Affordable Care Act public exchange system.

Officials cited the story of a Montana resident who faced $43,000 in out-of-pocket costs because his insurers claimed that his cancer was a pre-existing condition and a Pennsylvania woman who ended with $20,000 in out-of-pocket costs related to an amputation.

Between 2018 and 2020, ACA exchange plan enrollment fell 27% in states that let short-term health insurance policies stay in force for 364 days and just 4% in all states, according to a study cited by the regulation writers.

The critics’ thinking: The drafting team received about 15,800 comments supporting and opposing their proposed regulations.

Critics of the departments’ proposed regulations argued that short-term health insurance competes well against ACA exchange plans, in spite of medical underwriting and the lack of ACA exchange plan premium tax credit subsidies, because the short-term health insurance policies are often cheaper and may offer coverage the better fits typical insureds’ needs.

An anonymous broker told the drafting team, in a comment posted on Regulations.gov, that the departments are making a mistake by adding restrictions on short-term health insurance.

“I’ve sold over 300 plans, and I’ve seen people get sick on them and never incur extra charges after their deductibles met,” the broker said. “First and foremost, so many ‘good’ doctors don’t take ACA plans, but they take short-term plans.”