Why Are Gas Prices Going Up?

This basic description of the economics of oil pricing that I wrote in 2012 (and which starts after this new introduction) remains largely correct. Many of the pricing, consumption, and production figures are different today, of course, but the key change in the petroleum world is that the United States, which was essentially tied with Saudi Arabia and Russia in petroleum production in 2012, has since far surpassed them. The fracking revolution, which was not front-page news 10 years ago, helped America increase its oil production from about 11.1 to 18.6 million barrels per day (or mb/d), while Saudi Arabia and Russia stayed about the same.

The result is that we’ve gone from importing roughly 8 mb/d of petroleum 10 years ago to actually being a net exporter in 2020. So we should be in Fat City, right? Unfortunately, as explained below, the oil market is global, and while our imports and exports are roughly in balance, we still import and export large quantities of oil and petroleum products in different parts of the country where logistics and pricing make sense to do so.

Moreover, oil consumption in the world as a whole increased from about 89 to 96.5 mb/d, as the global economy grew, helping hundreds of millions to escape poverty. For example, the number of vehicles in the world grew from 1.15 to 1.4 billion during that time. Meanwhile, oil production dropped significantly in some countries—over 4 mb/d in Libya, Mexico, and Venezuela alone. The increased production in America, along with nearly 4 mb/d more from Canada, Iraq, and Brazil, made up the difference.

Despite all of the gyrations in this business, oil prices had more or less stabilized in 2019 in the $50-to-$60-per-barrel range. Then COVID-19 hit, putting a major damper on economic activity and depressing oil prices, which briefly even dropped to zero in intraday trading in early 2020. Part of the problem is that petroleum production is a very capital-intensive business that’s not easy to throttle down or up. Shutting down a car factory is trivial in comparison. But oil eventually stabilized around $40 per barrel and started climbing in late 2020 all the way through 2021, as COVID slowly receded and economies started to return to normal faster than oil production ramped up.

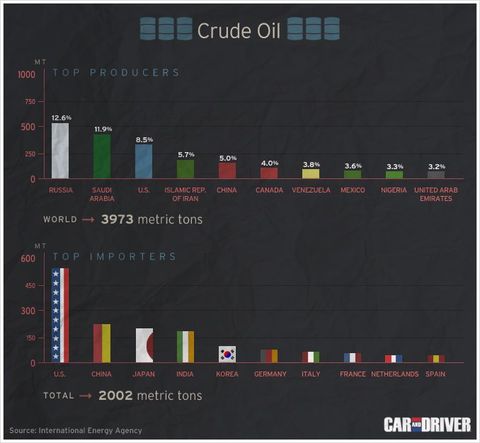

Now we have Russia invading Ukraine and being hit with extensive and well-deserved economic sanctions. Since revenues from oil production supply about half of the budget of the Russian government, shutting off that oil flow would be the most severe potential punishment. But since Russia is the world’s third-largest oil producer, supplying about 11 percent of the world’s consumption, anything done to disrupt Russian oil deliveries will drive up oil prices—as we’re seeing today. This is particularly true in Western Europe, where several countries foolishly tied themselves to Russian energy supplies.

Unfortunately, energy contracts tend to be long-term, so there are no easy substitutes for Russian oil. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have the most potential among the big suppliers to ramp up oil production, but the Biden Administration is not on good terms with either government. And some other potential sources, such as Iran and Venezuela, are under embargo and governed by regimes hardly more savory than Russia’s. Besides, after 30 years under an incompetent dictatorship, Venezuela’s oil production facilities have deteriorated, and it’s unclear how much production could be increased.

Of course, the environmentalists should be happy, as high gasoline prices are the best method of discouraging consumption and reducing CO2 production. But even the environmentally focused Biden Administration understands that the American public’s demand for affordable gas exceeds its desire to solve global warming. Still, for now, Americans seem willing to accept high gas prices as the price of punishing Russia without engaging in active hostilities.

Sadly, these painful sanctions are not hurting the Russians much. Oil is specifically exempt from the banking restrictions imposed on Russia, so the country can keep selling oil to its existing customers. Even if Russian oil sells at a discount, and in reduced quantities, with oil prices twice as high as they were a year ago, the revenues pouring into the Kremlin are not much changed. Taking the next step and extending the banking sanctions to oil sales would really hurt the Russians, but it would further increase the price of oil—and gas—worldwide, hurting us as well.

So the question is how much financial pain will we accept and for how long, versus how much can the Russians stand. Current gas prices are painful but likely tolerable for some time. The more effective sanctions, however, might produce major political pushback. Either way, I suspect the world’s oil markets will likely adjust and find a new equilibrium by the end of the year. We probably won’t get back to $2.50 gas, but we won’t be double that, either. —CC

This story was originally published in 2012.

The price of crude oil—and, more important, gasoline—has climbed to painful levels once again. As of early April, the quote for Brent crude, the international yardstick, was about $126 a barrel—only some $16 below the $142 peak seen in the summer of 2008. But domestic West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude is only getting $107 a barrel—a full $38 below the 2008 peak. Meanwhile, we are told that U.S. oil production is up, gasoline demand is down, and we are even exporting gasoline to foreign countries. So why is the price of gasoline, at an average of $3.84 per gallon for regular, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, within five percent of the 2008 peak when domestic crude is fully 26 percent lower?

It’s easy to imagine oil-company conspiracies when seeing these figures. But as usual, the truth is a bit more complicated—and less satisfying. As the chart below shows, the price of at the pump does move in concert with crude-oil prices, although the proportionality between the two varies with market conditions. According to John C. Felmy, the chief economist for the American Petroleum Institute, since 1968, the retail price of gasoline has averaged about $1.17 above the price of a gallon of crude oil (in 2012 dollars). That figure includes the average state and federal taxes of about 49 cents (varying from 26 cents in Alaska to 67 cents in California, Connecticut, and New York), the cost of refining the crude into gasoline, the transportation and distribution costs, and the refiner’s profit.

By that standard, a refiner who starts with Brent crude at $126 for a 42-gallon barrel of oil, or $3.00 per gallon, would be charging about $4.17 a gallon for gasoline. Refiners using WTI crude would charge $3.72. In America, most refiners are stuck paying the Brent price, because the WTI crude tends to pile up in Cushing, Oklahoma, and is only conveniently available for refineries in the Midwest. But if you blend these prices in a ratio of three parts Brent to one part WTI, you get an average projected retail price of $4.06 per gallon. Since gas is selling for about 20 cents less than that, the current price does not suggest price gouging.

As an aside, during the huge run-up in the summer of 2008, the gap between the price of crude and the $4.05-per-gallon retail price was 60 to 70 cents, suggesting that despite the record gas prices, there was no profit being made in the refining business. However, companies in the crude-oil drilling and delivery end of the business made a killing.

The current low margins in the gasoline business reflect soft demand for the product in the U.S. As of early 2012, we are burning about 8.4 million barrels of gasoline a day (assuming 42 gallons a barrel, that’s about 14.7 million gallons an hour, or 4083 gallons a second). As staggering as that quantity is, it’s about 13 percent less than the 9.7 million barrels a day we consumed at the peak in July 2007. A part of the reason for this lowered demand is a reduction in driving. As a nation, we drove a peak of 3030 billion miles in 2007 and only about 2963 billion last year.

That’s about 2.2 percent fewer miles, and we’re driving those miles in more efficient cars and trucks. According to a study at the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute, the cars and trucks sold this year will average about 28.5 mpg by the federal Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards. That’s up from less than 25 mpg in 2007 and reflects a shift from trucks to cars and the introduction of efficient technologies, as well as a greater preference for smaller vehicles.

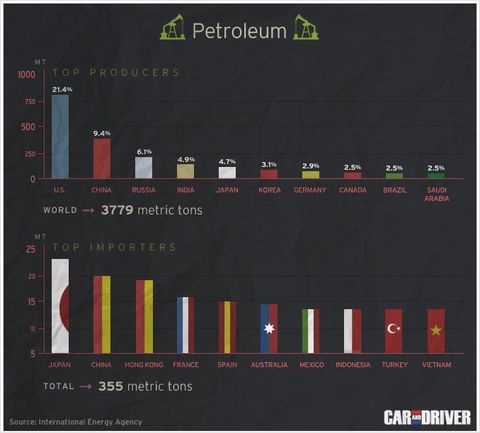

Low U.S. demand would suggest a lower price, according to classic economic theory. But crude oil and gasoline sell on world markets, and global demand is on the rise (see the chart below). From a low of 85 million barrels a day during the recession in 2009, current global usage is about 89 million barrels. That exceeds the previous global peak of 86 million barrels in 2007.

This hearty appetite for oil includes all its products, which is one reason why the U.S. is exporting a small fraction of its refined gasoline. American refiners can make a better profit selling gasoline overseas than they can in the States because “there isn’t a lot of excess capacity around the world,” according to the API’s Felmy. And as do wheat farmers or airplane manufacturers, oil refiners sell their products to whoever is willing to pay the highest price.

This demand for oil among the world’s growing economies—China’s, India’s, Brazil’s—has been running up against limited supplies, which is one reason crude oil prices are rising. Another price driver is the fear that the growing tension with Iran over nuclear weapons development might disrupt that country’s oil exports—the fourth largest in the world—or motivate the mullahs in charge to mine the Strait of Hormuz and disrupt the shipment of about 20 percent of the world’s oil supply.

Even as oil gets more expensive, the Chinese can afford to buy it because their economy is robust and their currency is getting stronger. In 2008, when Brent crude was $142, it took 993 Chinese yuan to buy a barrel. Today, if crude hits the same level in dollars, the Chinese will only need to spend 894 of their stronger yuan for a barrel.

For the Europeans, it has gone the other way, owing to their financial crisis. European motorists pay very high gas taxes, but as the euro has declined, European gas prices have escalated even faster than in America. When oil cost $142 at the peak, that translated to €99. They’re paying almost that many euros to buy a barrel of today’s $125 crude, which is why gasoline is back up to $9 a gallon in some European countries.

There aren’t many signs of relief going forward. In the short term, gas prices usually increase with the transition from winter to summer fuel and the start of the summer driving season. Moreover, in July, Sunoco plans to close a crucial refinery near Philadelphia that currently provides about one-fourth of refined products on the east coast. This development is unlikely to do anything to reduce gasoline prices.

In the longer term, although the Chinese economy is slowing, that country’s economic growth—and its demand for energy—will continue to increase to the tune of about 7.5 percent annually through at least 2030. To a greater or lesser degree, the same goes for India, Brazil, and several other fast-growing economies. As a result, even though America, Europe, and Japan are taking measures to use fuel more efficiently, global petroleum demand is expected to reach at least 105 million barrels a day by 2030—18 percent higher than today’s rate.

The world is hardly going to run out of oil in the near future, but much of the easy oil—the kind that simply gushes from the ground—has been harvested, and future supplies will be harder to access and require greater investment. Think deep water and deep wells. Even so, oil’s high energy density and liquid convenience will continue to make it the fuel of choice for anything that moves.

This all means upward pressure on oil and gasoline prices in the future. Prices will undoubtedly fluctuate, but the trend line is not likely to turn downward. For now, only biofuels provide any meaningful competition, and they will become more economically viable as gasoline prices increase. Meanwhile, if you’re in the market for a new vehicle, keep fuel efficiency in mind—or at least avoid a long lease.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io