When Detroit Auto Workers Defended a Diego Rivera Mural Against Protests From the Rich

Image: Detroit Institute of Art

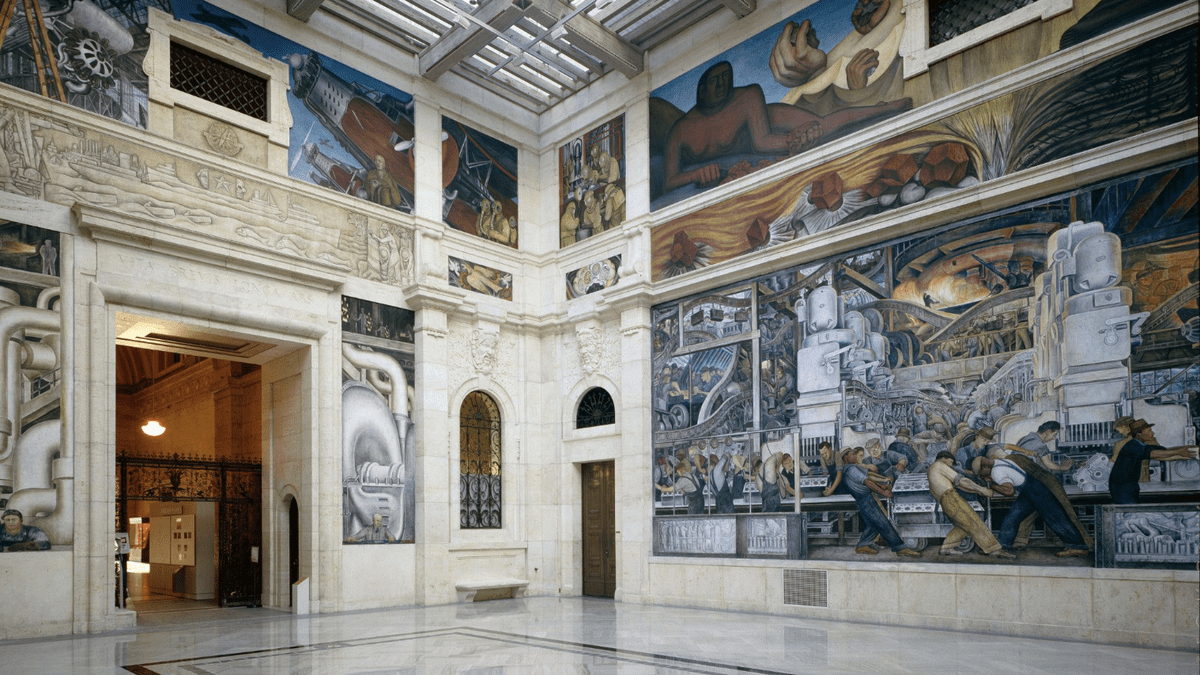

It’s one of the most iconic places in Detroit: The fantastic Diego Rivera Detroit Industry mural covering all four walls in the Garden Court at the Detroit Institute of Arts. When the 27 paintings were unveiled to the public, everyone from Catholics to business leaders to socialites demanded the walls be whitewashed. That’s how you know you’re doing art right.

Diego Rivera and his wife, the artist Frida Kahlo, spent over a year in Detroit, where both would create some of their most famous works of art. It was in the city that Kahlo miscarried the couple’s first child, leading to her heartbreaking work Henry Ford Hospital (The Flying Bed). Rivera was fascinated by the Rouge River plant, then the largest factory in the world. Rivera would later call the Detroit Industry murals the greatest works of his career. He was deeply moved by the power of the workers running these great machines, and called the mural “a great saga of the machine and of steel.”

You can spend hours picking apart the symbolism of the murals. Bright scenes of workers toiling on giant machines in fiery factories dominate the work, but there are also bits dedicated to medicine and the chemical and military industries that once called Detroit home.

It was one of these scenes that particularly irked the city’s sizable Catholic population. They protested the mural before it was even completed, over Rivera’s communist sympathies. When they actually saw the painting, they demanded its immediate destruction due to what they felt were unfavorable allusions to their religion. From a New York Times article in 1933:

The murals recently completed by Diego Rivera in the Detroit Institute of Arts will not be white-washed without provoking indignation among artists here, it appeared yesterday from comments by persons well known in the art field. Although varied points of view were expressed by individual artists and officers of organizations, the burden was in opposition to the group in Detroit that is agitating for the removal or whitewashing of the murals.

Dispatches from Detroit have reported that the frescoes recently completed by Rivera, widely known Mexican artist, have aroused the ire of Catholics, who called them irreligious and charged that one painting in particular, the “Vaccination” panel, was a caricature of the Holy Family. Rivera, who has come to New York to begin work on a mural painting for the Rockefeller Center, denied the charge in an interview here.

The “Vaccination” panel portrays a child, supported at the left by a nurse in uniform, wearing a nurse’s cap which, antagonists of the picture charge, resembles a nimbus. At the right of the panel appears a physician administering vaccine to the child. This figure has been represented by opponents of Rivera as intended to caricature Joseph, as they charge, the other figure represents the Virgin. Above these figures appear three scientists engaged in research, who have been likened to the three wise men. At the bottom of the canvas are animals, said by Rivera to suggest only the source of the vaccine, but by his opponents to represent animals usually portrayed in representation of the Holy Family in the stable.

Rivera was raised Catholic in a predominantly Catholic nation. Of course that symbolism is going to sneak in. Detroiters also objected to the nudity in some of the panels. And problems arose when the wealthy rulers of the city saw how the murals glorified workers. From the Detroit News:

“There were all kinds of objections,” said Linda Bank Downs, author of “Diego Rivera: the Detroit Industry Murals,” the authoritative work on the subject.

She ticks off the complaints:

“It was the height of the Depression, and a foreign artist was hired to paint the murals. Then there were nudes in it — and a laboratory with a child being vaccinated, painted in the style of a nativity scene. As for the upper classes,” Downs added, “they didn’t like the working classes invading their museum. They were offended by that.”

Denounced as communistic, sacrilegious and anti-American, a councilman just four days after their inauguration introduced a resolution before the City Council demanding they be scrubbed off the walls (which wouldn’t work with frescoes).

None of the city’s three daily newspapers liked them. To the Detroit Times, they were an “enormity” that would hit visiting public “like a bolt.” The Detroit News called them “foolishly vulgar” and, somewhat surprisingly, “a slander to Detroit workingmen,” and called for their removal. The Detroit Free Press called them “decadent art, adding, “they cannot be taken seriously.”

They weren’t wrong; the art certainly helped embolden Detroit’s workers, who had been throughly demoralized as they fought for their lives through the Great Depression. According to Frida: A Biography, by Hayden Herrera, after someone called in a bomb threat on the museum, auto workers offered to stand guard over the mural, an offer that left the Communist Kahlo absolutely ecstatic. The artistic community also rushed to Rivera’s defense.

On of the city’s most important leader at this time, Edsel Ford, paid for the whole thing and was unfazed by the controversy. He is also featured in the mural in full color, so that probably helped. Other industrialists and capitalists in the paintings aren’t treated as well — the glorifying focus clearly favors the workers. Harry Bennett, for exampled, is featured talking down to a group of disgruntled auto workers. Bennett was Henry Ford’s gray-faced goon, best known for shooting wildly into crowds of striking workers and beating the living daylights out of my guy Walter Reuther.

While his rich friends raged, Edsel simply released a statement on the mural, saying “I admire Rivera’s spirit. I really believe he was trying to express his idea of the spirit of Detroit.”