The Racing Game That Changed Everything Was Built on Lockheed Martin Technology

Real life has a funny way of underwhelming sometimes.

It’s 1993. Sega’s AM2 division, the studio led by Yu Suzuki, the mind behind Hang-On, Space Harrier, Out Run and After Burner, is making great progress on one of its big arcade tentpoles for ’94, Daytona USA. The NASCAR-inspired racing title will be the first to utilize groundbreaking 3D graphics technology sourced from General Electric Aerospace Simulation & Control Systems, enabling texture mapping and filtering for visuals more lifelike than any seen in the medium before.

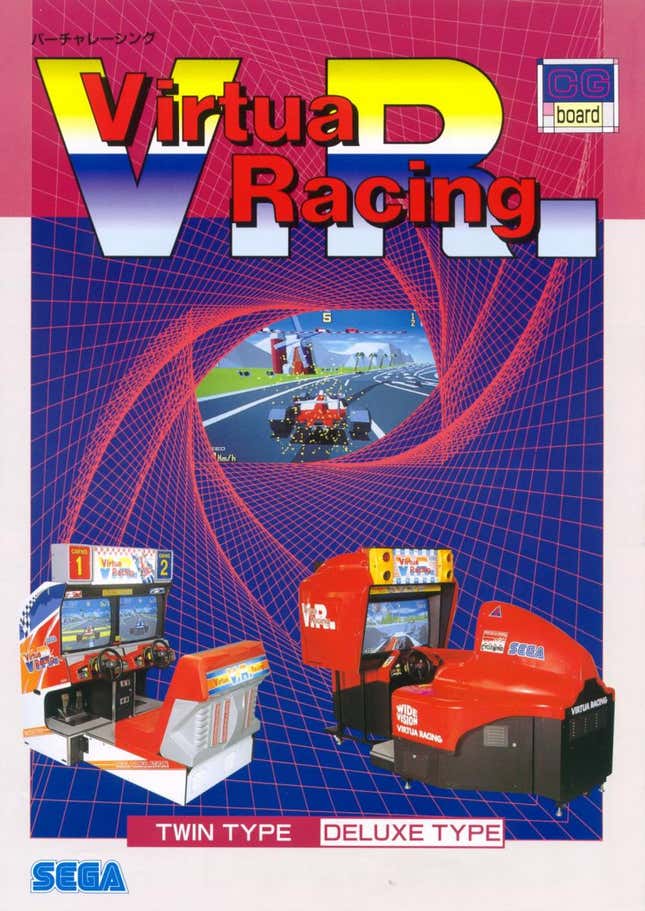

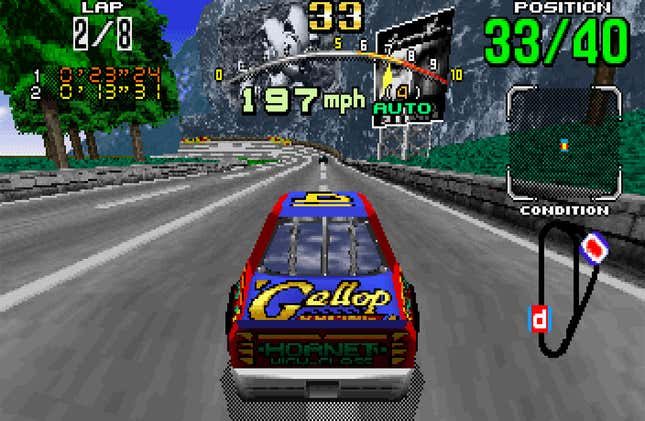

Suzuki’s last racing game, 1992’s Virtua Racing, was fast and striking but lacked the hardware to apply textures to 3D models. Mountains in Virtua Racing were piles of defined triangles painted shades of brown. The asphalt and grass alternated stripes of grays and greens, respectively, because one consistent color would’ve made depth perception impossible. But in Daytona USA, trees looked like trees, not verdant spikes jutting from Earth. Rock formations were distressed and layered; glass reflected the sky.

It couldn’t not blow anyone away, and yet Suzuki was underwhelmed. So he reached out to Sega designer and artist Jeffery Buchanan for help.

“I just sat down, I made out these big lists,” Buchanan told me. “I’m like ‘yeah, someplace on this side of the cliff, just put this giant dinosaur fossil in the cliff.’ Just find really interesting things to set in locations. Some of our [other artists] were modeling this ship for something — I don’t remember what [game] that was originally for — but they ended up putting that ship off in one area.”

That explains the 19th-century clipper outside the final corner of Daytona’s Expert course, as well as the space shuttle on a launch pad immediately before it. As a thanks for the designer’s contributions, Suzuki had one modeler dedicate a statue to “Jeffry” elsewhere on the same track. This is how we all remember video games from the ’90s: Dazzling and colorful, no idea too absurd in the pursuit of fun. But developers had to find the fun — on silicon architected by the world’s biggest defense contractor, used to train soldiers and astronauts.

It Started With a Phone Call

The agreement Sega entered into with GE in September of 1992 couldn’t have been more obvious for the Japanese video game giant. Sega needed the hardware to accelerate its development of 3D arcade titles. Getting there alone would take too long, and GE had the tech.

For GE, however, deals like this presented a possible lifeline. The late 1980s had not been kind to the military-industrial complex, which had to contend with both a lack of conflict and a sweeping overhaul of the Department of Defense’s procurement process, ostensibly designed to increase competition and stamp out fraud.

It was the job of people like Bob Hichborn to find new clients for GE’s graphics products, which began with the Visual Docking Simulator built for NASA’s Apollo space program. By the ’80s this morphed into a series of Compu-Scene image generators, used to train tank operators, pilots and the like. These were entire rooms filled with racks of beige boxes, capable of producing a “couple of thousand polygons at 30Hz,” in Hichborn’s words, with crude, linear textures that modulated solid colors across vast surfaces.

A screenshot from a C-130 flight simulator running on Compu-Scene II technology from the early 1980s. “You can see the use of linear texture [and] how it just modulated the color across the polygon,” Hichborn said.Image: Courtesy Bob Hichborn

By the end of the decade, Hichborn was responsible for leading product demonstrations as a part of GE’s Advanced Technology Group, headquartered just across the street from Daytona International Speedway. He cold-called all the big names in interactive entertainment when he and his team weren’t repurposing military property into video games.

“I had total creative freedom to do anything I could dream of within the context of selling simulation products by day,” Hichborn, who lost his voice in 2014 after decades of presenting demos, told me via email. “But the fun really didn’t start till after 5 p.m. when folks started heading out the doors to go home. In these ‘after hours’ I would take my team of interns and we would turn the various training systems into spaceships, race cars, raft rides down river rapids or whatever we could dream up.”

Hichborn pored through trade magazines, digging up contacts at the likes of Disney and Universal. Not exactly the sorts of leads his bosses had in mind, though he wasn’t too fussed about that.

“You can imagine the interest the creative folks at these places had, which led to them wanting to come visit us in Daytona,” Hichborn said. “Only one problem: GE was a military defense contractor and I was a lowly little engineer going to our marketing group telling them that Disney wanted to come in and see all this cool interactive entertainment content we were working on.”

A photo of a test berth where customer image generators were evaluated before site installation, circa mid-to-late 1980s. “You can see the size and length of these systems,” Hichborn told me, “and the amount of hardware in each rack was mind-boggling. 80- and 300-MB disc packs were the storage medium, with smaller system updates done with magnetic tapes.”Image: Courtesy Bob Hichborn

Hichborn says he “consistently got into a bit of trouble” for inviting theme-park builders to check out technology built to military budgets. “But who’s going to refuse a request from places like Disney? That was my ‘ace,’ so to speak.”

GE showed Disney a demo of a prehistoric raft ride on a motion rig with computer-generated dinosaurs; this would morph into DisneyQuest’s Virtual Jungle Cruise several years later. GE had already been sponsoring Epcot’s Horizons world-of-tomorrow attraction through most of the ’80s. Hichborn’s involvement only deepened those ties, spurring a GE installation at Disney’s Celebration, Florida community and the creation of the Edison Adventure film shown at Horizons, which melded classic cel animation with 3D graphics.

But Hichborn’s most pivotal cold-call came in 1990, when he gave Sega a ring. The executive secretary to the CEO answered, heard his pitch and didn’t say a word.

“I asked her if everything was okay, and she said ‘yes, we need to talk to you.’”

The Key to the Next Generation

“In the defense industry it usually takes a year or more and hundreds of thousands of dollars just to get through the contract design, design reviews, tons of meetings and paperwork on any particular government contract,” Hichborn said. “But within just a few weeks after my cold-call, two vans full of execs and design reps from Sega of Japan showed up in Daytona at our facility.”

One of them was Yu Suzuki. At the time, Sega was still developing its Model 1 architecture, the system that later powered Virtua Racing and Virtua Fighter. “Model 1 was pretty crude by today’s standards, but at the time it was pretty good,” GE Aerospace’s John Lenyo told Tom’s Hardware Guide in a 1998 interview. “By comparison, it looked a lot like the Compu-Scene systems from the Apollo Space Program days, except that it went into a $15,000 arcade game instead of a multi-million dollar simulator.”

A scan of GE marketing materials for its Compu-Scene SE series of image generators, likely from the late 1980s or early 1990s, according to Hichborn. Note the screenshot in the lower right. By now, the technology had advanced to using color textures derived from photos.Image: Courtesy Bob Hichborn

When it was time for GE to make the trip to Sega in November of 1990, they brought a tape with them. It showcased a racing simulation running in real-time at double the framerate Virtua Racing would by the time it launched, fully texture-mapped with trilinear filtering, to give faraway surfaces viewed at oblique angles a more natural appearance. The hardware used to run it cost $1.5 million, according to Lenyo. And what better venue to capture and recreate for the demo than the one across the street from GE Aerospace’s home base: Daytona International Speedway.

It was exactly what Suzuki had been looking for, after years of designing games that cleverly layered, scaled and rotated 2D sprites to convey the sensation of navigating through a 3D space. According to Hichborn, the deal was signed just weeks later. GE estimated its involvement helped Sega bring its vision to market 14 months earlier than it otherwise could have.

But the deal wouldn’t be publicized until September 1992, within days of Virtua Racing’s worldwide launch and, more alarmingly, two months before GE sold the entire Aerospace unit to Martin Marietta for $3 billion. Take note; acquisitions are a core theme of this story.

This photo was taken in 2001 at an arcade at the Ontario Mills Mall in California. Daytona USA may be almost 30 years old, but you can still find cabinets in arcades across North America today. These wide-screen “Deluxe” installations have become rare, though.Photo: San Francisco Chronicle via AP

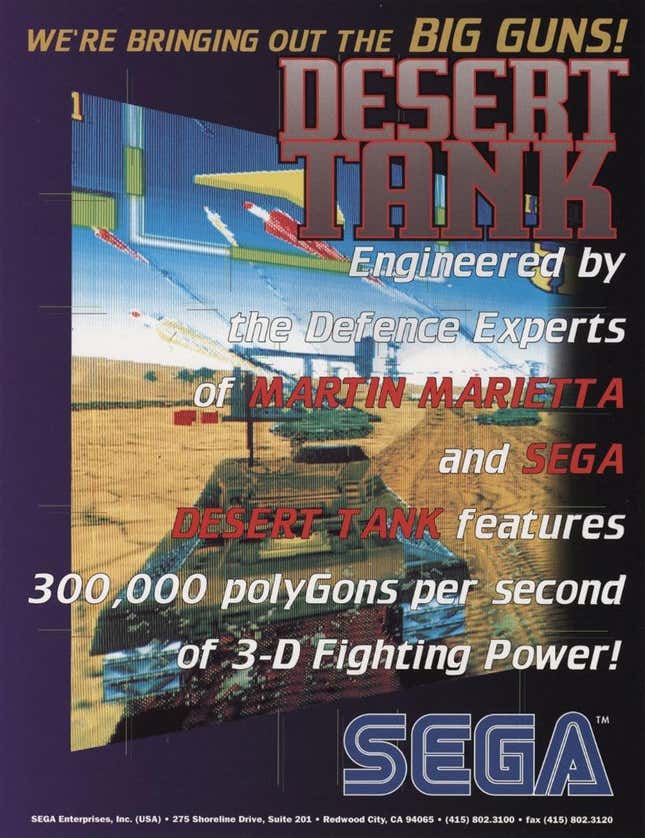

The Tank Game By Tank People

Daytona USA, the first game running on the Model 2 board Sega co-developed with the GE team now under the Martin Marietta umbrella, entered location testing in Japan late in the summer of 1993. And despite its breakthroughs, it wasn’t the only 3D, texture-mapped arcade racing game designed using hardware from a military contractor. Namco’s Ridge Racer, built on Evans & Sutherland tech, released around the world in the fall of that very same year.

Meanwhile, the Martin Marietta crew moved onto another new project, one both familiar and, strangely, totally unlike anything it had ever built before: A video game.

“Sega saw an opportunity to have us build a game with a marketing angle,” Hichborn told me. The pitch was: tank combat, designed by the same people who make tanks. Rather predictably, it was called Desert Tank.

It’s hard to convey how surreal it is to see the Martin Marietta logo right beside Sega’s on the title screen of an arcade game, but then this was fully a joint effort between the two companies. AM2’s Hiroshi Kataoka split producer credits with Paul Palma of Martin, while Suzuki oversaw development.

Credits also included designer Dan O’Leary and programmers Sean Purcell and Erick S. Dyke. Those three would start Orlando-based studio n-Space shortly after Desert Tank’s completion. The company closed its doors in 2016, having shipped more than 40 titles in 22 years. Dyke passed away in 2008 and Palma in 2018.

“If you look at the time between 1984 and 1994 … we went from absurdly simplistic wireframe renderers on the Atari 800 literally to Jurassic Park, in those 10 years. And the PlayStation launched the same year. So, you go from ‘no 3D rendering’ to ‘all 3D rendering.’”

“I got a degree in mechanical engineering with a focus on thermodynamics,” O’Leary said over the phone. “I wanted to work for a race team or a car company. But I graduated in the Clinton era, and there was a recession in play, so there weren’t a whole lot of jobs. Between that and me not having great grades, I didn’t do that. But most of the reason for my grades was, I was always busy playing with stuff on the computer, trying to figure out this whole real-time rendering thing that was happening.”

O’Leary first became interested in 3D graphics in 1984, when he discovered a wireframe renderer written for Atari’s 8-bit home computers by Tom Hudson of the magazine Analog Computing. The program allowed users to create and view objects in 3D by linking points in three-dimensional space.

“If you look at the time between when that came out, 1984, and 1994 when we founded n-Space, we went from absurdly simplistic wireframe renderers on the Atari 800 literally to Jurassic Park, in those 10 years. And the PlayStation launched the same year. So, you go from ‘no 3D rendering’ to ‘all 3D rendering.’”

Fresh out of college in 1992, O’Leary took a role at United Engineers as a contractor for GE Aerospace. He scripted training exercises for tank simulations for about a year, implementing scenarios given to him “by the military, or by somebody else.” And then he caught wind that GE was learning how to make video games.

“I found out about this project that was happening literally in a locked room with this kind of group of outcasts that wore shorts,” O’Leary said. “You know — the kind of classic ‘internal innovation team’ kind of idea.” O’Leary pitched demos he’d made to his boss and was eventually selected to join Dyke and Purcell, who had already started work on Desert Tank.

“There were only like seven people on the team. It was this small room, with a Model 2 cabinet, a Daytona cabinet, with the hardware boards out so that we could program the ROM [chip that held the game files] and test the game.”

The tools available to the development team on their Sun workstations were so bad, O’Leary told me, that most of the models he created for Desert Tank were drawn on graph paper before their vertices and faces were placed into the renderer using a text editor. While support for texture mapping was one of Model 2’s calling cards, color textures were initially beyond its capabilities. Surfaces had a face color, modulated by another grayscale layer over top to lend the model its distinct texture. Certainly crude by today’s standards, but cutting-edge compared to flat planes.

How to Make a Video Game

Video games don’t get much simpler than Desert Tank. The player controls an unrealistically fast-moving tank with an objective to either destroy the enemy’s base or stop a nuclear missile launch in the allotted time, without being destroyed themselves. Sega hoped the project would help its new partners understand basic game design concepts that would inform Model 3 and beyond, helping Martin Marietta architect future hardware that would better meet Sega’s needs.

“It was a rushed project,” O’Leary said. “Working with Kataoka, a new producer who didn’t really speak a lot of English, from across the world, with a company that honestly didn’t know how to make games. Just a bunch of guys trying to figure it out as we went along. It was a challenge.”

Another Model 2 project running late complicated matters further, creating a hole in Sega’s release schedule that meant O’Leary and company had to cram six months’ worth of work remaining on Desert Tank into a third of the time. The Martin side of the dev team was moved to Sega’s headquarters in Japan for those final two months of production, working side-by-side with Kataoka and Suzuki to get the game over the line.

Hichborn recalls asking Suzuki — “as close to a video game Yoda as you could get back then” in Hichborn’s words — to try the game for himself as it neared completion. “He looked at me and said he doesn’t play games, he watches others play. He said that’s how he learns if a game is good or not, by the players’ reactions to the controls, gameplay, visual scenes, et cetera.”

Suzuki told Hichborn that he wouldn’t be able to critique the experience if he was too busy playing himself. The Sega legend also steered Desert Tank’s gameplay toward a more scripted direction and away from the variable, programmed artificial intelligence Hichborn’s team had imagined, that would’ve ensured no two play sessions unfolded identically. Suzuki’s philosophy was that players would memorize a little more with every run, and keep spending quarters until they knew enough to make it to the end.

“Even the shooting patterns of our enemy tanks were like ‘miss, miss, hit’ or ‘miss, hit, miss,’” Hichborn said. “[The player would] recognize a certain type of enemy and their shooting pattern, and would know they would have to destroy it before a ‘hit’ was en route.”

Desert Tank’s music and audio was composed by David Leytze, an American musician who started his career at Sega doing the sound effects and voice acting for Daytona USA. It’s David who tells you to “please select a race course” at the start of Daytona, and admonishes you over the radio for “burnin’ up the tires!” Leytze lifted many of his lines from Robert Duvall’s crew-chief character in Days of Thunder. “I’ll bet I watched that movie about a hundred times, just trying to figure out” what to say, he told me.

“Not immensely proud of the soundtrack [for Desert Tank],” Leytze reflected. “I don’t know that it really went over well. I got a lot of backlash after the fact from the American team, but nobody ever told me while we were working on it. But I kind of chose to do an orchestral-type thing instead of like a heavy-metal, hard-driving rock-type thing, and I think their vision of it [was different.]”

This Is Real3D

Desert Tank never landed in the annals of Sega’s arcade hits alongside Virtua Fighter and Daytona USA. The Killer List of Videogames’ Arcade Preservation Society estimates just six of its more than 12,000 members have ever claimed to own Desert Tank cabinets. Of those, only three were supposedly original dedicated machines, not hacked-together reconstructions using the original board. Comparably, the site classifies Daytona USA as “very common,” with 154 examples owned by its community over the years. Ironically, what few Desert Tank cabinets made it out there were very clearly painted-over Daytona rigs. The miniature stock-car shell that the player sat in was merely refinished camo beige and brown for Desert Tank.

So the tank-game-made-by-tank-people idea didn’t set the world on fire as Sega hoped. Still, Hichborn’s hunch to apply simulation-derived 3D graphics tech to video games proved an astute one. It at least warranted continued collaboration between Sega and Martin Marietta that produced a successor to the Model 2 platform. Model 3 launched with Virtua Fighter 3 in 1996, one year after the defense giant merged with Lockheed to form Lockheed Martin.

But not everyone at the company believed in the new business.

“There were definitely people at Martin that felt like this was kind of a distraction — that it was kind of beneath them, I think,” O’Leary told me. “It wasn’t a strategically-aligned kind of business move. But it was such a small thing. This was a company that had rooms full of giant image generators for sea, land and air. And I think it was smart to try and commercialize. But in the end that didn’t really work out too well I think.”

Shortly after the merger was finalized, Lockheed Martin spun off its newly-acquired graphics arm into a company called Real3D. Beyond the department’s work with Sega, Real3D looked to sell its own hardware direct to consumers in the form of PC graphics cards, which were just beginning to take off in the late ’90s. O’Leary, Purcell and Dyke left Martin Marietta in 1994 to start n-Space before the merger and Real3D’s subsequent formation.

“The hardware world for visual simulation disappeared, because all of the money [was] in entertainment.”

“The idea of Real3D was that it was going to be a small, lightweight commercial group, right?” O’Leary said. “And then they ended up moving, I don’t know, 40, 60 percent of the people over there so it became this giant, enormous [group]. It was a defense organization overhead trying to compete in a consumer product space.”

Gene Lynch, whose EPL Productions company created the Edison Adventure film for GE’s Epcot installation, directed the final Model 2 release in 1998 — a rail-shooter called Behind Enemy Lines. This was the GE/Martin/Real3D crew’s second stab at game development after Desert Tank. And while it manifested as a more visually stimulating game, benefiting from three years’ worth of refinements and understanding of the silicon, it also once again highlighted the difference between making combat simulators and making entertainment.

“When the original design of [the game] came out, [the enemies] were all wearing camouflage,” Lynch told me. “And Yu Suzuki was always saying ‘I can’t see anything, it’s all too dark.’ It’s because, well, the camouflage is working!” Lynch laughed. “I had to convince all of the military individuals that, look, we have to kind of go towards like a ‘James Bond-bad-guy’ thing here. These guys gotta be running around in yellow jumpsuits … we’re telling a story.”

Although Behind Enemy Lines was a modest success in Europe, Lynch told me, the game didn’t enjoy the same reach in the U.S., due to the declining relationship between Sega and Lockheed Martin around the time of the game’s completion. “The [cabinets] were built and waiting in Japan, but [Sega] was like ‘if we’re not going to work this out, we’re not going to release the game.’”

Never mind the impact Lockheed and Sega’s collaboration had on the course of 3D graphics. The business wasn’t sustainable. And to the old guard of defense, it was downright offensive.

“One time when you were working in any kind of simulation — especially a military simulation company, like a Lockheed or a [Silicon Graphics] — you were never allowed to use the words ‘emulator’ or ‘game engine,’” Lynch said. “That was total taboo, because you’re just demeaning the value of everything that they were. They got product out there that they’re selling for $400,000, $500,000, $600,000 a unit, and you’re going to take this little plastic box the size of a book and tell me it can generate the same graphics quality? And I can go down to a toy store and buy it?”

The first home version of Daytona USA released a little more than a year after the arcade original, in tandem with the Sega Saturn’s U.S. launch in May 1995. It ran at about a third of the framerate of its arcade counterpart, with a significantly reduced rendering distance and heavy display borders (which you’d see on a TV, but I’ve cropped out here) to save on resources.Image: Sega

Murmurs of upcoming projects followed Real3D and Sega. At one point, media reported the military spinoff was working on a derivative of its R3D/100 chip that would’ve amplified the rudimentary polygonal capabilities of Sega’s slumping home console, the Saturn. It never came out. Neither did “Model 4,” despite an anonymous Real3D employee repeatedly name-dropping it in a 1998 interview with Hardcore Gaming. Model 3 marked the end of the partnership.

The arcade experiment never offered much relief for the military-simulation business, which had all but dried up by 1996, as then-Lockheed product manager Joe Cox recalled to me.

“I was the one who kept the books,” Cox said. “I knew it cost $15 million to put a bunch of engineers and design a simulator and get the first customer satisfied. And I knew that we weren’t making that much money. We were never covering our costs. We might sell 50 simulators, but we needed 80 to cover our costs. And I knew that was going to fall apart.

“The hardware world for visual simulation disappeared, because all of the money [was] in entertainment. And I can [speak to that] working for Lockheed Martin until 1999, barely surviving every month with a paycheck.”

Going Home

Between 1996 and 1999 Sega released 23 titles, plus revisions, on the Model 3 hardware. Among them was Sega Super GT, known outside the States as Scud Race. Created by the same team as Daytona USA, Super GT traded its predecessor’s stock-car roots for European sports-car racing, featuring four cars that competed in the 1996 BPR Global GT series.

It was a stunning showpiece for Model 3’s massive lift in performance over the Model 2. A single car in Super GT employed 3,000 polygons, more than triple that of Daytona USA’s Hornet. “Suffice it to say that if we made, say, the Ferrari from Super GT on the Model 1 board [the one used for Virtua Racing in 1992] we would use about half the entire capacity of the board,” director Toshihiro Nagoshi was quoted in Next Generation magazine’s April 1997 issue. “If we displayed two Super GT cars, we’d have no more polygons left.”

In simplest terms, Model 1 is said to have pushed 180,000 polygons per second, without textures. Model 3 could handle two million. More than 11 times the rendering capability — in a matter of four years. Game consoles wouldn’t surpass it until the arrival of the PlayStation 2, Xbox and GameCube in 2000 and 2001. (There’s long been debate as to how Sega’s own Dreamcast, released internationally in 1999, compared.)

Model 3 owed its power to a pair of Real3D’s Pro-1000 chips. The Pro-1000 architecture was extremely high-end, never intended for sale to the public. But Real3D recognized an opportunity to distill its know-how into silicon that consumers could buy, to seize the burgeoning market for PC graphics accelerators.

Arcades generated half of all gaming revenue in 1990, according to historical data from Pelham Smithers by way of Bloomberg. By 1993, it accounted for a third. And by 1998, spending on PC and console gaming individually eclipsed spending at arcades. Model 2 and 3 were the past; the home was where Real3D needed to be.

And that’s when the bottom fell out. In 1996, Real3D won a contract with Intel, which had recently purchased California’s Chips and Technologies, to co-design a graphics card codenamed “Auburn” and eventually released as the i740. Real3D sold its version of the card at retail under the name Starfighter, paying homage to Lockheed’s Cold War-era F-104 Starfighter aircraft.

On paper, the i740 seemed like a winner. This was the ’90s, after all; anything attached to Intel seemingly couldn’t fail, and PC OEMs were impressed enough to sell their own brand derivatives of the chip. “In less than a year, almost a hundred partners had signed up to produce an i740-class [add-in graphics board] and began buying inventory,” longtime graphics analyst Dr. Jon Peddie wrote for an Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers retrospective. Intel confirmed its belief in the product by buying a 20-percent minority stake in Real3D in January 1998, a month before i740’s launch.

But the i740’s real-world performance didn’t meet the hype. Practically all graphics cards interface with PCs through PCI slots, a standard for connecting add-on components to a system’s motherboard. The i740 was different: It bet on a new type of connection called the Accelerated Graphics Port that opened a dedicated, direct channel to the CPU and allowed the attached processor to tap into system memory much faster than a conventional, PCI-based alternative could.

Thanks to those throughput gains, Intel believed it could get away with the i740 carrying very little video memory of its own, unlike conventional graphics cards. This would enable Intel to save money on every unit and pass those savings along to the consumer, ideally making the i740 a compelling value option against the dominant and much pricier high-performance cards of its day, like 3dfx’s Voodoo 2 and Nvidia’s RIVA 128. Unfortunately, commandeering system memory to store textures had a funny way of bottlenecking everything, as Ben Hardwidge wrote for Custom PC Magazine:

The first problem, of course, was that using system memory and its interface wasn’t anywhere near as fast as using on-board graphics memory. The other problem was that the need for the graphics card to constantly access system memory ended up starving the CPU of memory bandwidth.

That was a big problem at a time when the CPU was still doing a fair bit of the work in the 3D pipeline. The growing use of larger textures in 3D games to improve detail made the situation even worse. What’s more … the AGP implementations on most Super Socket 7 motherboards just weren’t designed with a card such as the i740 in mind.

The i740 was plenty ambitious, as Cox will tell you. But it also had the deck stacked against it.

“I don’t believe that Intel thought that we would be successful on that job. We actually made a part that worked and we tried to sell, but Intel wasn’t going to let it be successful. I don’t believe that anyone thought it would actually work. It was a proof of concept.”

When asked why he felt Intel “wouldn’t let it be successful,” Cox said it came down to dollars and cents.

“We [had to] go out and build something that could be competitive on the market, and so we said ‘we could do it this way’ and we [could] have this co-design with Intel … but all we need on a package is three more pins, or five pins. And they look at you and they say ‘we’re not going to that, each pin costs two cents.’ What’s 10 cents? Well, everything when you’re selling hundreds of millions of parts. And so that’s a $10-million decision for us.”

The i740 launched in February 1998 and was discontinued by the summer of ’99. Real3D and Intel were working on successors all the while, but they’d never see shelves. In October, Lockheed Martin washed its hands of Real3D, selling most of its assets to Intel while ATI swooped in to hire remaining staff, including Cox.

“I had no idea what we were going to do … I had 10 employees, and every one of them had been interviewing with ATI and left me out, I didn’t know anything about it,” Cox told me. “And the biggest day of my career was the night I went home and there was a message on my analog phone system that said ‘Joe, your whole group has been interviewing with ATI and we’ve all told him we’ll take the job if you’ll be our manager.’”

Cox remained at AMD, which purchased ATI in 2006, until December 2020, when he retired after 24 years at the company.

Seven-time Formula 1 champion Michael Schumacher plays Ferrari F355 Challenge, a simulation racing game designed by Yu Suzuki, in Tokyo in 2003. F355 Challenge utilized Sega’s NAOMI arcade hardware, which replaced Model 3 and employed the same architecture as the company’s final home console, the Dreamcast. Photo: Clive Mason/Getty Images

One Thing Always Led to Another

I took on this story wanting to know how a company that made war machines architected the technology that enabled my favorite game of all time, the game that changed my life. I got that answer, and yet, if anything, now I’m even more confused. How do you change the course of an industry and peter out? How can you produce hit after hit and still not make the numbers work?

“I think people had the sense that this could be big, but we didn’t make a ton of money,” Cox summed up to me. “I mean, GE had thousands of employees in Orlando. It certainly didn’t pay for those thousands of employees. And the reality is it was a very small group of people who did that. It wasn’t complicated.”

It really wasn’t. It was just a thing to do, a way to make a quick buck from research and development that was being underutilized in peacetime.

There was no precedent for it. Innovation was too rapid. Engineers needed to learn how to be artists. A company that never questioned who its clients were suddenly had to develop retail strategies overnight. The domain shifted from shopping malls and amusement parks to homes. When all of that is taken together, it’s really no wonder Real3D folded in four years.

But if you’re fortunate enough to remember how Daytona or Virtua Fighter or Super GT stood out to you as a child standing in an arcade, amid a barrage of strobe lights, mechanical clunks, synthesized engine noises and 12 songs playing at once, it stops making sense.

Thirty years since Lockheed Martin flirted with making entertainment, the defense contractor recognizes Unreal Engine, not anything it produces itself, as “the future of training.” A legacy that extends back to the very birth of 3D graphics now depends on the framework that powers Fortnite and a growing number of in-car infotainment systems, running on the same GPUs preferred by gamers and crypto miners alike.

It was inevitable. Training simulators don’t need to look flashy. They need only be accurate. Once the defense sector had a handle on that, everything else was frivolous.

“I remember we used to go to a military conference, where they [demonstrated] simulators,” Cox told me. “It was 2005, and I’d go there and I’d say ‘why are you guys still doing this? Have you not seen the Xbox 360?’” Cox had just led a team of ATI engineers to create the 360’s innovative graphics processor. “The reality is they don’t like change, and [their concern was] ‘how can we ensure the accuracy?’”

As Cox explained, there are not nearly enough pixels on any screen to accurately convey what your eyes see in the world around you. Fudging model proportions is a non-starter; if a sim isn’t precise, it’s not serving its purpose, and nothing can come at the expense of precision.

That wasn’t the future Hichborn and others imagined when they turned training systems into theme park rides. Decades later, the longtime Lockheed employee finds himself wondering about an alternate history.

“I don’t mean this in a bragging vein, because I’m sure at some point this technology would have worked its way to the gaming industry,” he said. “But what if I listened to the GE marketing folks and stopped this personal folly of seeing beyond military training to something different, something bigger?”

Each individual failure led to an acquisition. Trade names may have fallen out of fashion; Daytona USA might’ve given way to Need for Speed to Gran Turismo to Forza Horizon. Yet every piece of knowledge, every breakthrough, wasn’t lost with them. There’s no reason to doubt Hichborn; the ability to create worlds behind screens was always destined to flourish into something beyond the purpose of destruction. But in this world, one cold call just so happened to hurry things along.