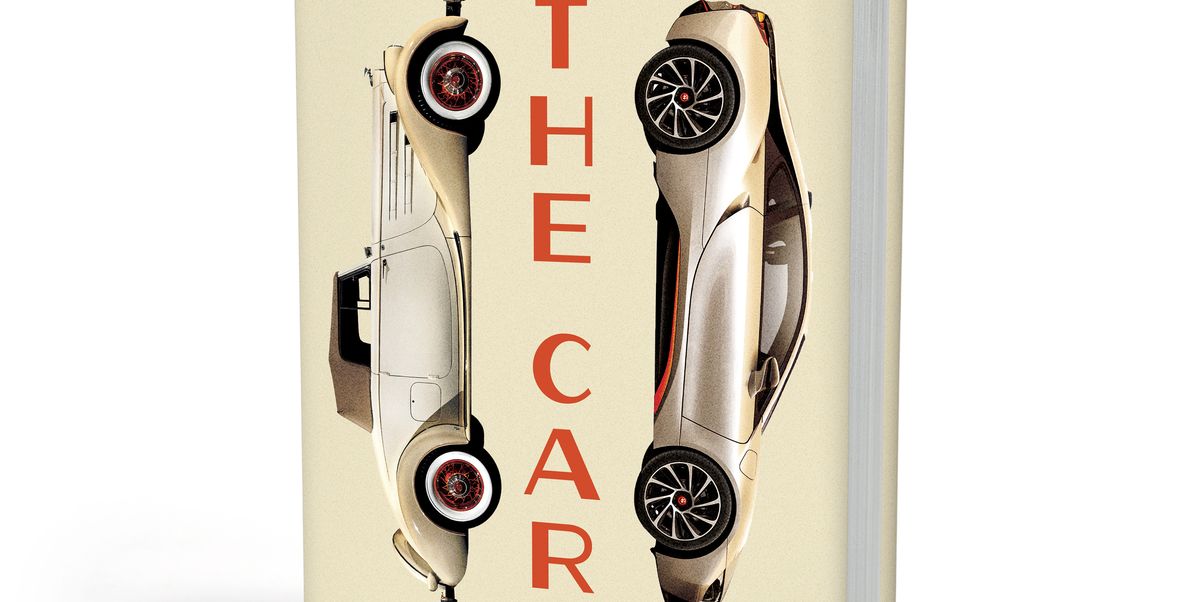

'The Car' Is a New Book That Takes a Joyride through Automotive History

Cambridge-educated journalist and author—and Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) recipient—Bryan Appleyard has mainly covered the arts and sciences in his books and articles, so in some ways, he seems unlikely as the writer of a fresh history of the automobile. Yet his new book, The Car: The Rise and Fall of the Machine That Made the Modern World is no ordinary history. Instead, it is a delightfully meandering romp through key milestones in the development of the automobile, and the repercussions that it has wrought—both amazing and horrific.

The Car: The Rise and Fall of the Machine that Made the Modern World

The Car: The Rise and Fall of the Machine that Made the Modern World

This simultaneous dichotomy is elemental to the book’s deftness and its allure. “I didn’t really realize what the thesis of the book was until several months after I’d written it,” Appleyard told C/D. “This is because there’s a sort of underlying thesis to the book, which was not just about cars. It’s about things in general. It’s the idea that people should be able to hold two ideas and thoughts in their mind. In this case, one is cars are good, and one is cars are bad. And it isn’t that one is going to cancel the other out.”

In other words, while the car has catalyzed profound and often problematic changes to our lives and our natural and built environment, that shouldn’t make us discard the sense of freedom, the spectacle of design and innovation, the cultural influence, and the capacity for speed and wonder automobiles have provided.

Yet it does raise a larger question of how to integrate this warring, bifurcated knowledge into planning for the future. “The more narrow thesis of the book is that cars, as we know them, are likely to change into something else,” Appleyard said.

And so it’s an end of an era which began in 1885, and I thought that was worth recording.”

Appleyard has a long history with cars, from his familiar childhood experience of “identifying every car that I saw passing” to a life littered with problematic or oddball vehicles. This list included a Triumph Spitfire, in which the passenger seat was a large cushion, a pair of Minis, and on to his current stable, which includes, as Appleyard said, “two relatively extravagant cars—a Bentley Continental GT, and a Porsche Boxster, which is on its last legs I think.”

Bertha Benz

Hi-Story/Alamy

Henry Ford and his Model T

Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

In his deep research into the broad history of the automobile, Appleyard was most startled by a couple of things. First, he was shocked by the languorousness with which the innovations that led up to the car accumulated. “I mean, I think the steam piston was invented in like the first century, or something,” he said. “And it took nearly 2000 years to get from there to the internal-combustion engine.”

Secondly, and relatedly, he was taken by the car’s immediate sociological precursor, which was not so much the wagon or the train, as much as it was another wheeled conveyance. “It was also surprising to me the degree to which the bicycle is a serious predecessor to the car, because the bicycle provided people with the idea of freedom of individual movement, over relatively long distances, at much higher speeds,” he said, noting that the contemporary chain-driven bike with two similar wheels wasn’t invented until the mid-19th century.

Appleyard’s choice of which stories or historical figures to focus in on—Bertha Benz, Billy Durant, Ferdinand Porsche, Sochiro Honda, and Ralph Nader, to name a few—was a challenge as well, mainly in terms of refining and editing their tales into something consumable. “I have this pathological desire to broaden details that I find fascinating, far beyond what anybody else could find fascinating,” he said. “So I had to struggle to get to the quite focused pieces.”

Autonomous Audi concept

Friedemann Vogel/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

Klod/Alamy

The book loses power a bit toward the end, in the discussions of electrification and autonomy, a fact that perhaps reflects Appleyard’s own uncertainty about the future. When asked if he might replace his beloved, if self-destructing, Boxster, with an EV, he equivocated. “Electric is interesting,” he said. “I couldn’t at the moment imagine buying an electric car as my primary car because the charging network is not as good as it should be. Obviously, there are bays of chargers, all of which are taken or some of which are broken.”

Yet, like many of us, he is coming around. “I couldn’t have it for long journeys. But for a car just in London, we would certainly consider an electric car,” he said. “So, we may get an electric car next, I suppose.”

This content is imported from OpenWeb. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.