Henrik Fisker Was A Coachbuilder Before He Started His Own Car Company

By all other accounts, Henrik Fisker has been pretty successful. He had a hand in designing some of the most iconic cars ever made, like the original BMW X5 and Z8, Aston Martin DB9, and Vantage. However, after years in the auto design business, Fisker decided to leave to pursue making cars. Since then he’s had two unsuccessful attempts — and a third currently on the ropes — at trying automaking. His first try didn’t take much effort.

The 2024 Hyundai Santa Fe XRT Is Better Off-Road Than It Needs Be

After leaving BMW, Fisker became design director of Ford-owned Aston Martin in 2001. There, he was put in charge of the design of the DB9 and was the sole designer of the V8 Vantage. Right before he left Ford, Fisker had become head of the brand’s Southern California-based Global Advanced Design Studio.

But around 2005, he wanted more. Fisker partnered with a man named Bernhard Koehler (who has also served in various automotive roles at BMW and Ford) and founded Fisker Coachbuild. The goal? To shortcut the whole automotive design and build process of making custom sports cars. According to a Wired story from 2007, doing so would avoid “enduring the indignities of focus groups, marketing data, and concept-to-production compromises.” Simply put, they wanted to make cars, without having to make cars. That’s how Fisker described his coachbuilding to Motor Trend in 2005:

In the auto world today, You have two types of design. There’s concept design, where automakers build cars to show the industry and journalists how great they are. Then there’s the production design, where that cool milled-aluminum center console from the concept car becomes spray-painted plastic. I wanted to build a car where some of these concept things actually made it into production. We don’t have marketing data here. If we feel a car is right, we just do it.

Image: Fisker

Fisker Coachbuild ended up with two models based on existing sports cars made with premium materials and exclusive design work by Fisker himself. The first was the Tramonto, which was based on the R230 Mercedes-Benz SL. The process of turning an SL into a Tramonto was pretty straightforward. Customers could choose whether they wanted their Tramonto to be based on an SL55 AMG or the monster SL65 AMG. Once that and any other Mercedes options were chosen, customers could let Fisker know through their Mercedes dealer or Fisker’s site that they had chosen their SL, and Fisker would arrange for the car to be taken from the dealer to its Southern California facility. Then the conversion from SL to Tramonto would take place over two months.

Image: Fisker

None of this was cheap, of course. Including the price of the donor SL, the Tramonto cost a bit over a quarter million bucks. But apparently, they were well built, with a carbon fiber body or aluminum body panels, and trunks lined with Alcantara. Initially, 150 were planned, but Fisker abruptly stopped production after just 15 were made.

Image: Fisker

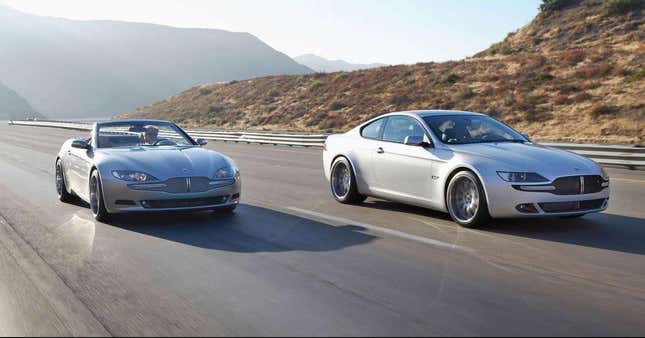

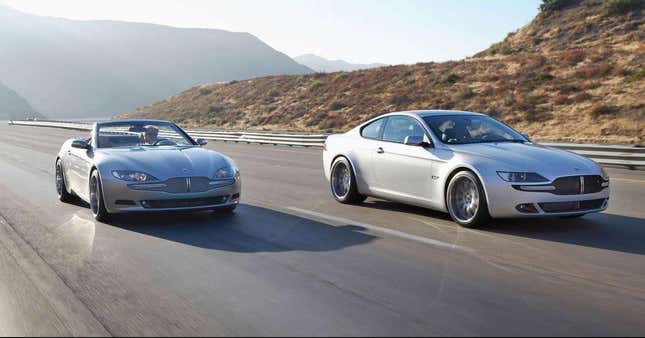

Fisker Coachbuild’s second model was based on the E63 BMW 6 Series. Fisker named this model Latigo CS after a well-known canyon road in Malibu, California. The process was the same as with the Tramonto. Buyers could choose to base their Latigo on either the base 645Ci or the V10-powered M6. In its design, Fisker said he wanted the Latigo to be beautiful. It’s not quite there, but it is an interesting design. The front fascia of both the Latigo and Tramonto were inspired by the F/A-22 Raptor fighter jet.

Image: Fisker

The Latigo wasn’t cheap either. Including the price of the 6 Series, the Latigo cost $197,900. The Latigo is even rarer. Like the Tramonto, 150 Latigos were planned, but just two were ever made: the prototype shown to the press and a customer order car. That car sold for just over $105,000 back in 2018.

Fisker went on to start Fisker Automotive the same year he stopped with his coachbuilding business, but that company ultimately went under and was later sold. While his current automotive venture looks like it might have the same fate, you can’t fault the guy for initially wanting to get into the automotive manufacturing game by doing something most automakers gave up on decades ago.