From the Archive: Paris by Pontiac Trans Am

From the January 1979 issue of Car and Driver.

It was [then–associate editor Mike] Knepper’s idea. “Why don’t you try to get a Trans Am to drive while you’re in Europe?” he asked. Immediately, that sounded like a terrific idea. Pick it up at Frankfurt-Main airport, drive it to Austria, then Stuttgart, then Paris, then give it back. “Terrific!” said GM Overseas Public Relations, so we called the travel agent and made our low-buck Apex reservations, Detroit–Frankfurt. When it was too late to change, GMO called back and said, “Hey, terrific, you can pick the car up in Antwerp!” So a deal was struck. We borrowed a Porsche 928 for the first leg of our trip, then flew from Stuttgart to Brussels to collect our Trans Am.

We spent a lovely afternoon with the irrepressible Tony Lapine, chief designer for Porsche and resident sage at their growing Weissach facility. Then, with considerable regret, left him to race off into a 40-minute traffic jam that interposed itself ‘twixt us and Flughafen Stuttgart, whence Sabena would transport us to beautiful Brussels and our waiting Firebird.

Belgium is not a fun place, especially when it’s cold and foggy. Belgium is not very big, either, and the high density of the small nation’s industrial plants means that you’re never far from a smokestack or some dispirited village that depends on a local coal mine for survival. As a result, the Belgian man on the street looks like one of H.G. Wells’s Morlocks.

Car and Driver

At Brussels, the customs guys waved us by without checking our luggage, but even so managed to convey the feeling that they recognized us as undesirable aliens, probably smugglers. Out on the sidewalk, I guarded the luggage while J.L.K. Davis went off in search of the Trans Am. I was watching Belgian cabdrivers jockey for position in front of the terminal, enjoying the near misses that occurred regularly, when a white Trans Am complete with screaming chicken decal and Chris Craft exhaust note came rumbling out of the maw of the parking lot, my wife at the helm.

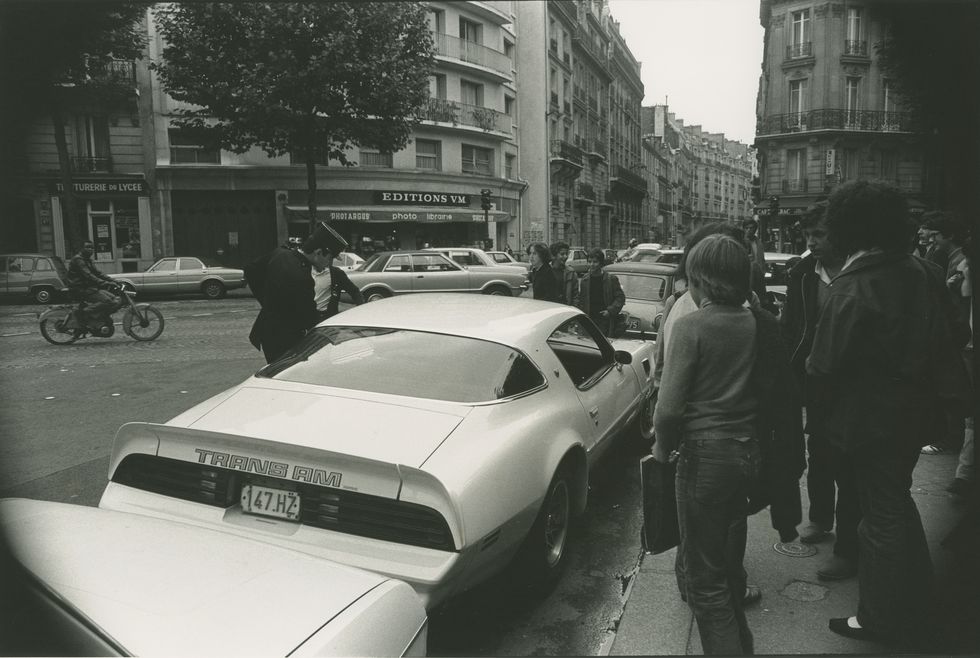

The Pontiac Trans Am is one of the last—but surely the best—of the Sixties’ silly cars. It is large for what it is supposed to do, claustrophobically small for whom and what it’s supposed to carry. It still manages to look sexy, and Pontiac’s enthusiast-engineers certainly seem to have found the secret of eternal youth and applied it to this clearly obsolete package, because a Trans Am is still a great kick, visually and dynamically, and that kick never came through as forcibly as when I saw our shiny white one shouldering its way through the Fiats, Renaults, and Citroëns in front of the Brussels airport.

If the customs people eyed our luggage suspiciously, the Trans Am was positively hostile about it. Pop the decklid. “Twit! You thought you’d get some luggage in here!” The specifications for this car say that it offers 6.6 cubic feet of luggage accommodation. This is true, but only if you’re hauling loose sand. You could carry quite a lot of clothing back there, but only if you left the suitcases at home. We managed to get one duffel bag into the trunk, but the other four pieces had to be stacked on the back seat. Hah! “Seat,” they call it, with considerable irony. It may look like a seat, but it is no place to sit.

From the Archive: Trans Am

It was disappointing to clamber inside and find an automatic-transmission selector lever instead of a four-speed manual, but otherwise it was predictably Pontiac—a little bit of home for two Americans who’d been away from the Big PX for 10 days. And after 10 days in a variety of Fiats, Porsches, and Citroëns, I unconsciously reached for the seat adjustments and was sharply brought back to another fact of American life: the non-adjustable seat (unless you count fore-and-aft). Maybe Nash wrecked it for all future generations of American car buyers . . . The cars from Kenosha came with reclining seats, not for driving but for sleeping, and this seemed to give reclining seats a bad name forever in the strait-laced American heartland. So there you are in America’s premier road machine, bolt upright for want of a simple product feature that’s been on German cars for 30 years, and standard equipment on even the meanest Japanese import. The front seats aren’t necessarily bad, but it is a shame that the driver and passenger must adjust their bodies to the seats, and not the other way around.

After a night at the airport Holiday Inn (another taste of home), we hit the road for Paris. Inside the Trans Am looking out, it seems neither large nor incongruous. In fact, it is every bit as comfortable on European roads as any middle-sized European car. The nose is long, but visibility is good. One knows where the four corners are, and the cut-and-thrust of European traffic—much more aggressive and challenging than anything American drivers normally experience—is managed with no more difficulty than one would know in a Porsche 928. It attracts more attention than a Porsche 928, and this is always a potential hazard, since continental Europeans must surely be the greatest gawkers in all the world and there’s always the danger that one of them will simply drive his Citroën Dyane into your lap in an attempt to see better.

As is our wont, we ignored the advice of the lady at the Holiday Inn and simply followed the autoroute that seemed most logically to lead to Paris. After a heavy morning traffic jam and a couple of fast laps around the airport trying to find our way out of the Brussels metro area, we blundered abruptly into the end of our autoroute and the vaguely marked beginnings of a detour. This is the sort of thing that normally leads to frayed tempers and surly early-morning repartee, but before we could start hassling one another the Wellington Monument loomed up out of the fog and we realized that our déviation had brought us to the edges of the Waterloo battlefield. We slowed the Firebird to a sightseeing pace and peered out into the gloom as one heroic monument after another rose up on either side of the road and discreet little signs pointed away toward places I’ve read about since I was a child. Surely, stumbling upon the scene of Napoleon’s last great battle this way, by accident, had to be more stirring than any planned arrival by tour bus could ever have been. Even the fog served to heighten the effect.

Car and Driver

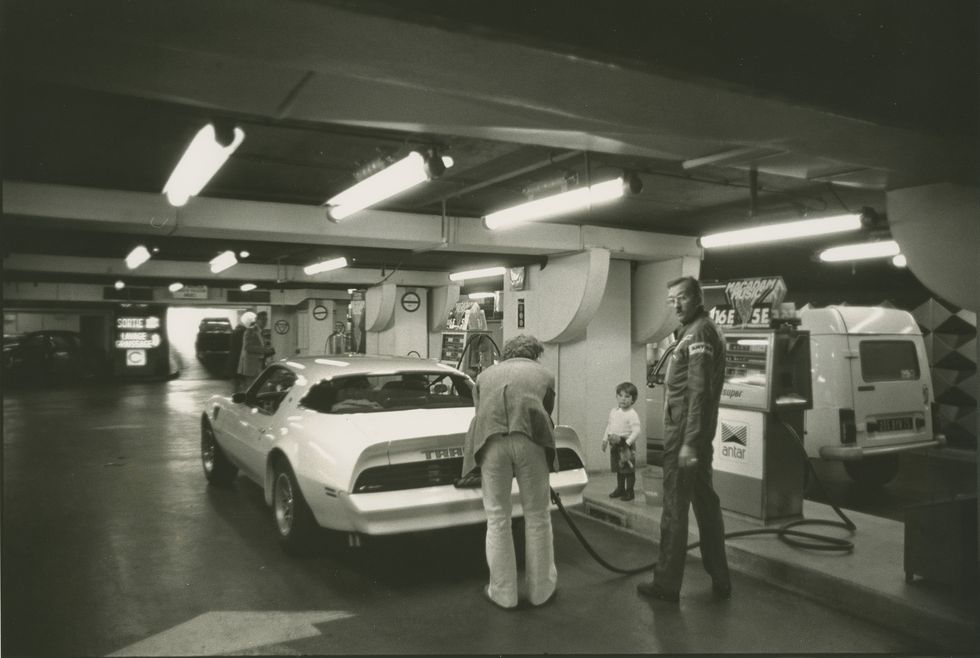

Back on the autoroute, we watched the gas gauge march steadily toward empty. We’d left Brussels with a quarter tank, and the big 400 was drinking that up at a hell of a rate. We wheeled off into the next service area and, oops, remembered the “Unleaded Fuel Only” decals scattered around on various flat surfaces where they couldn’t be missed. What to do? We called GM in Antwerp and asked their advice. Nobody knew. One thing was for sure, Belgian and French gas stations were not equipped with no-lead pumps. Finally, someone in the factory service department said to put premium in it. This is exactly what the station attendant had been telling us for twenty minutes while we took up space at his pumps. I had my doubts, but the official voice of General Motors on the telephone said, “Fill it with super,” so we filled it with super, 1060 Belgian francs worth, 62.4 liters of the stuff. That’s almost $40 in what we used to call “real money.”

Now fully aware of what it was costing Car and Driver to have me roaring along the autoroute in the Energy Crisis, thinking of the Belgian homes that might have been heated this winter with the petroleum I was using up, I eased back onto the highway and let it slowly rise to 90 mph—typical Renault/Simca cruising speed in these parts. (This newfound prudence was also based, in part, on my fear that all that expensive premium gas was going to melt the catalyst and send us down in flames like a Fokker Triplane.) When we crossed the border into France, the sun came out and the countryside opened up, becoming more hospitable somehow. The French national speed limit is approximately 80 mph, so we weren’t fudging by much, and it felt wonderful to let the Trans Am run at design speed without keeping one ear glued to the CB and the other to the radar detector. In Europe, one can turn up the stereo and go fast to the strains of Bach, or Waylon Jennings. Very civilized.

In this mode, another American cultural byproduct intruded on our reveries—rattles and squeaks. American cars, even expensive ones, rattle and squeak. The new computer-developed jobs from GM and Ford are better in this respect, but still not up to the level of the imports. It was annoying to be blissfully cruising along, enjoying fine French weather in a good car on a smooth road, and yet be vaguely troubled by a variety of persistent thumps and resonances.

Car and Driver

Our arrival in Paris was uneventful. Guys in corrugated Citroën vans—potential suicides for the most part—screamed by on both sides and tried to out-drag the Trans Am at every intersection. School kids couldn’t take their eyes off of it, even American-baiters like the one who stuck his face in the window and told us, “This car is obscene!” We got the proper obeisance from the doorman at the Crillon and found ourselves parked in the midst of two BMW coupes, a Ferrari 400 automatic, a Cadillac, and a number of other serious high-roller units. Somehow, the Pontiac looked right at home in that company, partly, I suppose, because it’s such a rare bird over there. Here, the endless parade of screaming chickens and all that post-GTO self-caricature get to be a little banal, but over there it’s exotic stuff, and the locals tend to be a little mesmerized by it all.

That, I suppose, was what it was really all about in the final analysis. It was great fun to be seen in a Pontiac Firebird in Festung Europa, but the actual driving pleasure was only about average, and visits to the gas station at 35 or 40 simoleons per tank very quickly took most of the remaining fun right out of the adventure. It made one thing absolutely clear to us, though. The most effective way to accelerate this nation’s shift to smaller cars would be t0 let gasoline rise to its supply-and-demand free-market price. An American can still rationalize the purchase of something getting twelve miles per gallon when he’s paying less than 70 cents for each of those gallons. Driving a Trans Am and paying the European price for gasoline would make small-car believers out of a host of American skeptics.