Formula One Should Throw Out Every Rule And Replace It With This One

Formula One is called the pinnacle of international racing for open-wheel single-seater racing cars, and it has been since the first season of the championship in 1950. In this context, the word “formula” applies to the set of rules to which all of the cars must be built. The series could otherwise be known as “Rules One” so why shouldn’t it just have one rule? It’s a rule that allows for open interpretation of speed, and brings engineers and drivers back to the fore instead of fake DRS passing and artificially deteriorating tires:

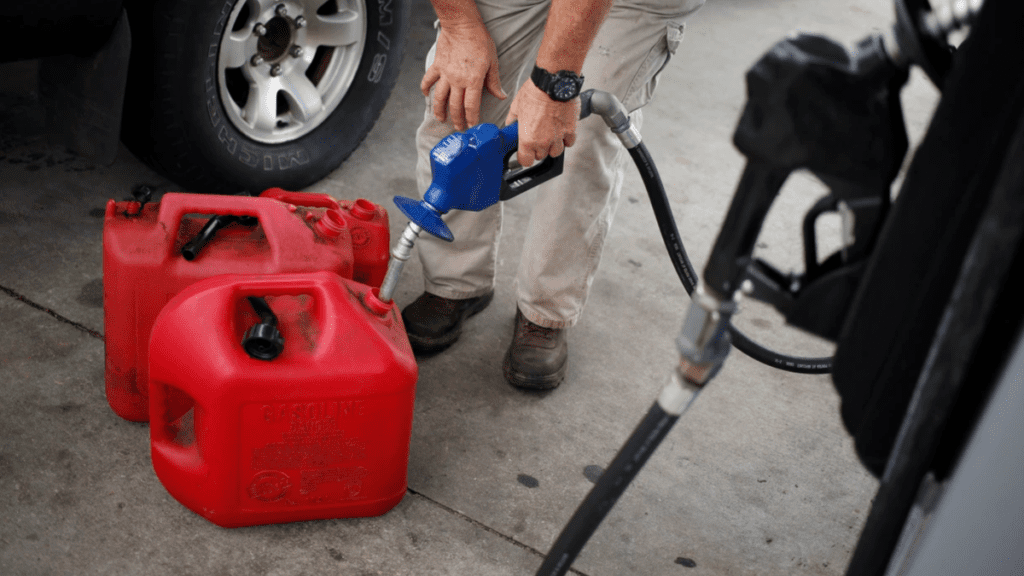

In the course of one two-hour Grand Prix, each car on the grid will be allowed two identical red plastic 5-gallon cans of whatever the cheapest gasoline is at a randomly selected gas station within ten miles of the circuit, as procured by the race marshals on the morning of the race. No additives, no spare tanks, no tomfoolery.

Shell Eco-marathon | Fully Charged

Ten gallons. That’s all you get. The longest Grand Prix by distance in recent years has been the Russian GP at Sochi Autodrom, which measured 192.466 miles. The shortest race every year is naturally the Monaco GP, which is just 161.734 miles by comparison, but that is an outlier, as every of the other Grands Prix are at least 189 miles long.

Broadway Star Wendell Pierce Is a True Formula 1 Fan

Okay, so we know the teams would need to achieve at least 19.2 miles per gallon in order to finish a race. Maybe a little more so we can still have a measurable sample at the finish to ensure the teams aren’t cheating. Current F1 cars, with all their hybrid gubbins and tire-saving strategy, achieve around six miles per gallon. The current cars are trash and the racing is about as bad as racing gets in any series around the world. It’s boring and processional in the worst kind of way. So throw those cars out and start with a fresh sheet of paper.

Image: Aston Martin

There are many ways that F1 teams could engineer in some better fuel economy. If there were no other rules applied to the building of the car, they could focus on aerodynamic efficiency, building a super slippery car that doesn’t have much downforce, but can really motor on the straights. Or the engineers could make a car that weighs very little, and has lots of downforce, so it can turn a fast lap time without needing a ton of power. Or they can rely more heavily on hybrid technology to keep the speed up without burning gas.

What’s faster, a Formula E car with a gas generator to keep the electric power at its peak, or a Japanese Super Formula open wheeler with a Prius powertrain? This is the kind of series where you could find out.

The Shell Eco Marathon-winning PAC-car IIImage: Shell

OK, sure, the cars need to pass the safety standards of the series, and the cars have to fit within a certain dimensional footprint. For the sake of tradition, these cars should still be open-cockpit and open-wheel. Beyond those simple regulations, the car can be whatever you want it to be, but you only get to burn 10 gallons of low-test 87-octane regular gasoline, maybe E15 if you’re lucky.

While I think the racing would probably get slightly slower at first, the extremely intelligent engineers behind each team could probably build the speed back up over the next decade, and they’d be working on experimental technology that actually develops efficient driving tech to the street. F1 hasn’t been street relevant in at least twenty years, so this would be an effort to fix that.

With wildly different methods of making the fuel numbers, it’s entirely possible that this theoretical Formula One would have a different winner each weekend, as some cars would perform better at some tracks than others. This could allow for so much more passing as cars make speed in different ways. Drivers would have to flex their skills to place the car perfectly in order to keep speed through the corner and not burn extra fuel. An incredible aero designer like Adrian Newey, or an incredibly efficient driver like Scott Dixon, could make all the difference in a season.

Goodness, I wish!