Drive like it’s 1885: What it’s like to take the tiller of the first car, a Benz Patent-Motorwagen

IMMENDINGEN, Germany — Set your time machine to August 1888. It’s hot, humid, and you’re in a small German town enjoying a refreshing pint of hefeweizen when an unusual noise breaks the silence. It almost sounds like a train, but it can’t be — there are no tracks for a train to travel on. The source of the cacophony appears halfway through your next sip: It’s carriage-like, yet there’s no horse pulling it and it’s eerily moving under its own power.

Back to the present (you can bring the hefeweizen with you). It’s hot, humid, and you’re relaxing in a small German town. Suddenly you hear a car coming — who cares? Unless it’s something really special, like a Glas 1300 GT, odds are you wouldn’t pay attention to it. However, in 1888 you would have witnessed what’s widely recognized as the first car take its first road trip with its inventor’s wife at the … well, not really at the wheel, because the steering wheel hadn’t been invented yet, but at the little metal tiller used to turn the lone, bicycle-like front wheel.

Carl Benz built the Patent-Motorwagen in 1885 and received a patent for his invention, which he described as a “vehicle with gas engine operation,” on January 29 of the following year. He essentially invented the car. Sure, someone else might have designed a vehicle with gas engine operation in 1882, and it may have worked wonderfully, but there’s no trace of it. Benz applied for and received the patent for the car, and his wife, Bertha, embarked on the first road trip — a 112-mile trek from Mannheim to Pforzheim and back — with her kids two years after that.

Now it’s my turn to take the Patent-Motorwagen for a spin over 130 years later at the Mercedes-Benz test track in Immendingen, Germany.

Smart but simple

One point worth clarifying is that this isn’t the first car. It’s one of the replicas built by Mercedes-Benz in the 2000s, so it’s an exact copy of the original. It starts, accelerates, and brakes just like the real thing, and I’m told that the dimensions and the mechanical layout are identical. Carl Benz restored the original Patent-Motorwagen in 1906 and donated it to the Deutsche Museum in Munich. It’s still there today.

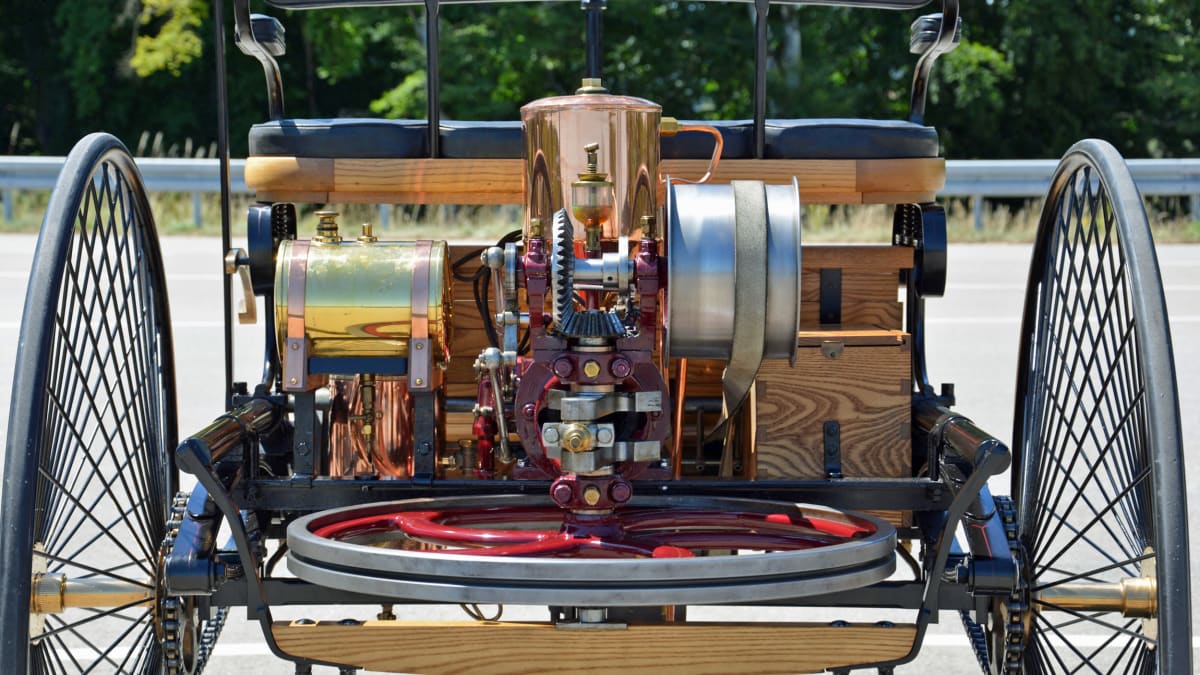

At first glance, there wasn’t much going on in the design department (in that there literally wasn’t one). From every angle the Patent-Motorwagen resembles an old car, one that perfectly embodies the “form follows function” philosophy. And yet, it’s a fascinating object to look at. It’s motorcycle-like in its simplicity and openness. There’s no body, it’s pretty much an engine and a bench-like seat dropped on a steel frame, so the mechanical components are clearly visible. That’s its beauty: It’s a mechanical type of seduction that began vanishing from the automotive industry many decades ago.

There’s not much of an interior, either. Before you sit in (on?) the Patent-Motorwagen, let alone take it for a spin, it’s interesting to notice how little it shares with the commonly accepted definition of a modern car. If it rains, you’re wet. If you’ve got a suitcase to take with you, tough luck. If you want to know how fast you’re going, take a guess. Relax: It’s not like there were speed limits to respect in those days. The only comfort-related equipment is a bench seat with padded armrests, a short padded backrest, and springs to keep your spine in one piece.

Even if speed limits were strictly enforced, speeding is the least of your worries in the Patent-Motorwagen. Power comes from a single-cylinder, 1.0-liter engine that develops about 0.75 horsepower at around 400 rpm and unlocks a top speed of roughly 10 mph. You’d have gone faster on a horse, though a slower trip was a fair tradeoff for not traveling accompanied by the smell of manure. Mounted horizontally over the rear axle, the engine spins the rear wheels via a differential, a leather belt, and a series of metal chains. It runs on petroleum-based ligroin instead of gasoline, and it features an open cooling system without a water pump, an open crankcase and a massive flywheel.

Where to start?

It’s nearly impossible to start the Patent-Motorwagen if you haven’t seen it done before; you wouldn’t know where to start (excuse the low-hanging pun). Remember, the 1.0-liter has an open crankcase, which means the crankshaft is casually hanging out the bottom end and it must be manually lubricated. In contrast, your car’s engine features a closed crankcase so the oil circuit keeps the crankshaft (and many other parts) lubricated. If you crawl under your car and come face-to-face with the crankshaft, you have a very big problem to deal with.

With this in mind, the first step is to ensure that several points (including the crankshaft and connecting rod bearings) are properly lubricated. Next, manually bring fuel into the carburetor; a small glass cylinder on top of the carburetor allows you to check the fuel level, though it’s not easy to see and you may need to shake the car a few times to get an accurate reading. Next on your to-do list is to verify the water level and top it off if needed. Finally you turn on the ignition switch, set the air-fuel mixture, give the flywheel a couple of swings to prime the engine, and use every muscle in the arm of your choice to spin it. The engine comes to life with a chuff-chuff-chuff that gradually gets faster. You’re not done yet: The final step is to adjust the air-fuel mixture so that the massive piston settles into a nice, even idle. Hop on, and you’re off.

Sitting on what feels like a fancy piece of patio furniture, with the Patent-Motorwagen shaking like an unbalanced washing machine under you, is rather intimidating until you realize a child could drive this rudimentary three-wheeler. Beyond the tiller, which is surprisingly light once the car gets moving, the only control is a lever that pokes out from the left side. It’s linked to a spring-loaded rod that shifts a leather belt between the idler drum and the drive drum. Pull it back to brake, leave it somewhere in the middle (at about 90 degrees with the ground) to engage neutral, and push it forward to move forward. That’s really all there is to it; there are no gears to shift and no pedals to stomp on.

Driving the Patent-Motorwagen in a straight line, on flat ground, and with no obstacles is like the first level in a Mario game: Do it once to get the basics down and you can do it blindfolded. With a top speed on par with a high-end riding lawn mower’s, the odds of getting into trouble are mercifully low. Braking is approximate at best, it takes a few tries to learn the lever’s response, but turning is a different story. The three-wheel layout is unstable by nature, the tires are thinner than a mountain bike’s, and the Patent-Motorwagen is top-heavy; it has more ground clearance than a Ford Bronco. Braking before a turn initially requires a stunning amount of concentration and just as much dexterity, but you get used to the handling eccentricities after a few minutes behind the tiller. It’s more enjoyable to drive than you might assume.

The past’s future

As primitive as it looks, sounds, and feels, Carl Benz’s Patent-Motorwagen was the future of mobility in the 1880s, and its significance can’t be overstated. If you’re reading this, there’s a strong chance you like cars. Whether you’re hoarding BMW E30s, restoring a 1970 Ford Mustang to showroom condition, saving up for a Jeep Wrangler to explore Utah in, or trying to squeeze 1,000 horsepower out of a Toyota Supra’s twin-turbocharged 2JZ-GTE, you’ve got this old thing to thank for your obsession. Even if you don’t like cars, you’ve got the Patent-Motorwagen to thank for not having to ride a horse to work when it’s 28 degrees outside. It’s humble and simple, but it changed the world.

Did the folks caught off-guard by the sight of Bertha Benz road-tripping in the Patent-Motorwagen realize the historical significance of what they were witnessing? I doubt it. It’s something to keep in mind as we get deeper into the 2020s. The phrase “the future of mobility” gets thrown around like confetti at Mardi Gras, but it’s nebulous — its definition ultimately depends on who you ask, where they live, and what they’ve got in the game. Benz’s Patent-Motorwagen reminds us that all it takes is one clever, well-timed invention to shape the future.