Axial flux motors: Mercedes and Ferrari’s edge in electric car performance

When drivers of future Mercedes AMG models stomp the accelerator of their electric performance cars, they’ll get extra oomph out of the batteries from something that sounds straight out of “Back to the Future.”

No, not flux capacitors, but axial flux motors.

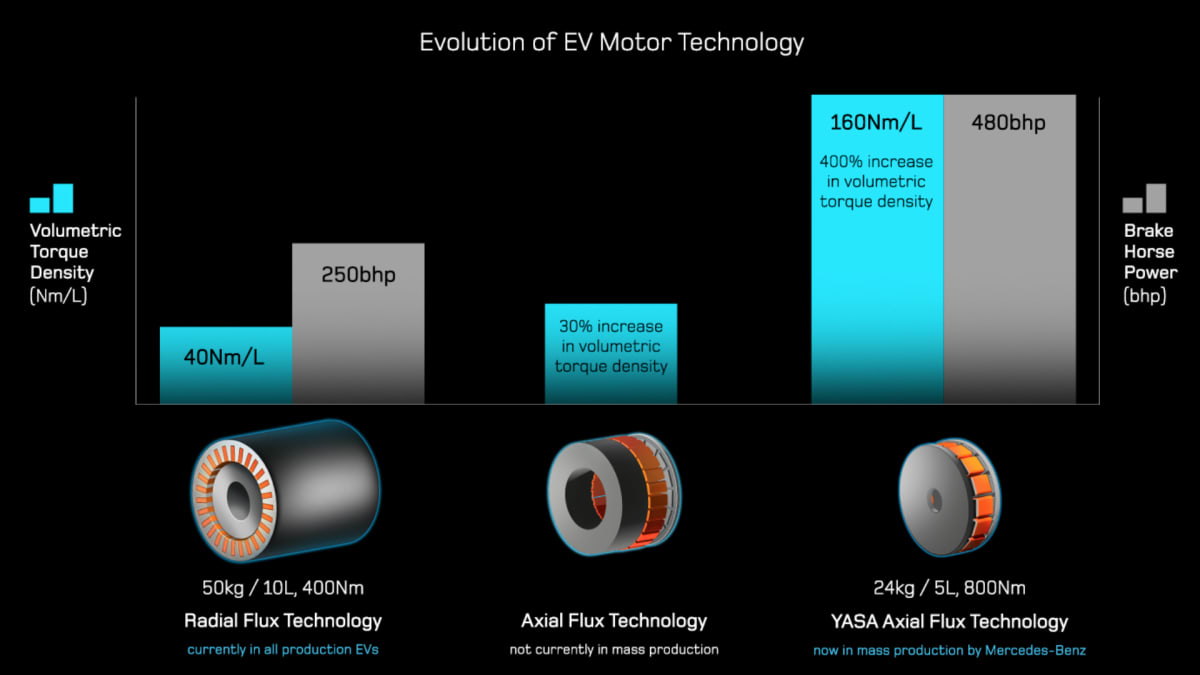

Mercedes-Benz AG and Ferrari NV are turning to this type of electric motor to generate headrest-hitting torque. Axial flux motors are much smaller than predominantly used radial motors, yet pack a more powerful punch.

High-end motors like these will be crucial to brands like AMG and Ferrari as they race to electrify the high-performance vehicles that earn prestige and bumper profits. All EVs offer the sensation of instant acceleration, from Nissan’s Leaf to Tesla’s Model S Plaid. Whereas in the combustion age, quicker times off the line and higher top speeds were achieved with more engine cylinders, manufacturers will differentiate performance EVs by getting the most out of batteries with lighter and more efficient motors.

“The power-to-weight ratio is really a record number, and much better than conventional motors,” Markus Schaefer, Mercedes’s chief technology officer, said of the automaker’s upcoming AMG electric vehicle platform. “It will make use of the small size of the motor.”

With each press of the accelerator, EV drivers push hundreds — and in some cases thousands — of amps of electric current to copper coils. When these coils are energized, they become electromagnets with attractive and repulsive forces. The magnetic force created by a stationary stator surrounding a rotating rotor produces the torque that turns the wheels of the vehicle.

In axial motors, rather than have a rotor spin inside a stator, disc-shaped rotors spin alongside a central stator. This leads the flow of current — the flux — to travel axially through the machine, rather than radially out from the center. Since the motor generates torque at a bigger diameter, less material is needed. Yasa, an Oxford, England-based manufacturer of motors used in Ferrari’s SF90 and 296 GTB plug-in hybrids, uses just a few kilograms of iron for its stators, reducing the mass of the machines by as much as 85%.

Yasa’s motors are the brainchild of Tim Woolmer, whose work on them were the focus of his electrical engineering PhD at the University of Oxford. Within a few years of earning his doctorate, Jaguar Land Rover made plans to use Yasa’s motors in the C-X75, a hybrid-electric two-seater with enough horsepower to rival the Porsche 918 Spyder, McLaren P1 and Ferrari LaFerrari. While JLR ended up canceling the project due to financial constraints, Yasa’s motors found their way into the Koenigsegg Regera hybrid hypercar, followed by the Ferrari SF90.

In July of last year, Mercedes announced it had acquired Yasa for an undisclosed sum and would put its motors in AMG models slated to launch starting in 2025.

“If you look at the history of automotive generally, the auto companies have wanted to have the engine, their core technology, in-house,” Woolmer said in an interview. “The batteries, the motors, this is their core technology now. They recognize the importance of having long-term differentiation in these spaces, so they have to bring it in-house.”

The most important aspect of axial motors is form-factor potential, according to Malte Jaensch, professor of sustainable mobile drivetrains at the TUM School of Engineering and Design in Munich. Their smaller size could allow carmakers to put one motor on each wheel, which isn’t feasible with radial motors.

Putting a motor on each wheel — or at least one on each axle — could translate into hair-raising EV driving performance. The innovation allows for torque vectoring that better controls how much power the motors send to each individual wheel for improved agility. High-speed cornering may help AMG and Ferrari drivers get over the lost roar of their eight-, 10- or 12-cylinder engines.

Yasa’s motors also could completely remove the need for a powertrain on the so-called skateboard underneath the middle of an EV, Woolmer said. That would open up more space for engineers to package batteries, make more room for bigger front and rear trunk spaces, or allow designers to experiment with new aerodynamic ideas.

The small size and light weight of axial motors won’t just benefit high-performance cars. They’re also finding a home in aerospace, leading Yasa to spin out its electric aviation division Evolito last year. The world’s fastest electric vehicle, Rolls-Royce Plc’s electric aircraft called the Spirit of Innovation, uses three axial flux motors to drive its propeller. The aircraft can travel around 380 miles (612 kilometers) per hour, making it faster than the Spitfire fighter aircraft that was powered by a Rolls-Royce V12 engine.

“The critical thing is their efficiency,” said Matheu Parr, the Spirit of Innovation project leader at Rolls-Royce. “This allows you to keep the weight of the aircraft low.”

Axial motors won’t necessarily be the death knell of radial motors, which deliver higher top speeds. This led Ferrari to use two radial motors on the front axle of the SF90, along with an axial motor on the rear axle. For the 296 GTB, handling was deemed more important, so only a lighter axial motor was used between the engine and transmission.

“It’s just a matter of what kind of driving experience you want to design for your customers with a specific engine,” said Davide Ferrara, Ferrari’s electric motors manager. “Different voices make sweet notes.”

Related video: