A 75-year-old Harvard grad is propelling China's AI ambitions

At a time when the US and China are divided on everything from economics to human rights, artificial intelligence is still a point of particular friction. With the potential to revolutionize everything from food production and health care to financial markets and surveillance, it’s a technology that sparks both optimism and paranoia.

One of the field’s most influential figures is Andrew Chi-Chih Yao, whose education and professional life have straddled the world’s two biggest economies. China-born and Harvard-trained, Yao is his country’s only recipient of the Turing Award, computer science’s equivalent of a Nobel Prize. After almost 40 years in the US, he returned to China in 2004. Now he teaches a prestigious yet little-known university class that has shaped some of the country’s biggest AI startups, informed government policy and molded a generation of academics.

“We have a very good opportunity in the next 10 or 20 years, when artificial intelligence will change the world,” Yao said in May 2019. He urged China to “take a step ahead of others, to cultivate our talents and work on our research.” The scientist, who rarely speaks to foreign media, didn’t respond to Bloomberg’s requests for an interview.

The “Yao Class”—an undergraduate computer science course at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, alma mater to President Xi Jinping and many of China’s ruling elite—has exerted a profound impact on the country’s technology pioneers and growing scientific prowess. Its graduates form a powerful network across the country, advising on each others’ projects and pooling resources and capital where needed.

Yao’s acolytes have created startups worth more than $12 billion at their peak, including Alibaba-backed facial-recognition giant Megvii Technology Ltd. and Guangzhou-based Pony.ai Inc. Others teach at top-flight American universities including Stanford and Princeton.

“Just his willingness to come back to China means a lot,” said Hu Yuanming, a Yao class student from 2013 to 2017 and the chief executive officer of computer graphics startup Taichi Graphics Technology Inc. His company is backed by Sequoia China, Source Code Capital, GGV Capital and BAI Capital, having finished its series A round of financing of $50 million in February.

Hu is a beneficiary of the Yao Class talent pool. Pony.ai’s Lou Tiancheng and Megvii’s Tang Wenbin advised Hu on founding his company, and he says hiring is easier for Taichi than for many small businesses. Current Yao students have undertaken internships too.

Driving force

One thing the US and China agree on is the vast potential of AI—a sweeping field that will define much future technology and which is now a key battleground in Washington and Beijing’s struggle for tech ascendancy. Given its potential for making weapons smarter, AI may also have major national security implications.

The US National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, chaired by former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, warned last year of the risks inherent in China’s growing grasp of the sphere. “If the United States does not act, it will likely lose its leadership position in AI to China in the next decade and become more vulnerable to a spectrum of AI-enabled threats,” the NSCAI report said.

Meanwhile China has framed AI as a “core driving force” in its industrial transformation and a “new focus of international competition” as it pushes for technological self-reliance. In 2017, the country set a target for AI-related industries to reach 1 trillion yuan ($148.2 billion) by 2030.

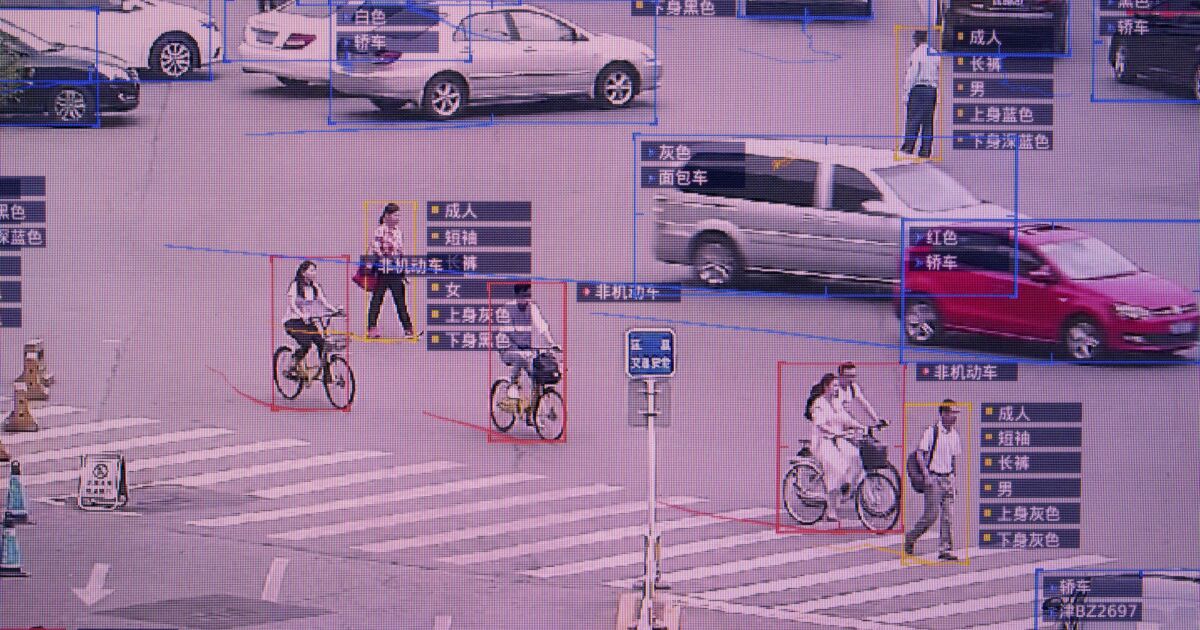

With the world’s largest pool of Internet users and an unprecedented amount of data, China has had marked—and controversial—success in AI, especially in fields like facial recognition. Companies like SenseTime Group Inc. and CloudWalk Technology Co. are among the sector’s most advanced globally. China’s share of global AI patent filing reached 52% in 2021, up from 12% in 2010, according to research from Stanford.

Some experts say China’s AI expertise is limited in scope and more focused on domestic surveillance than world domination. But regardless of whether China comes to dominate AI, or merely maintains its position as one of the top players, Yao is a key part of the nation’s toolkit.

Born in 1946, Yao emigrated to Taiwan as a child. He has described the upbringing he shared with his two siblings as happy and middle-class with an emphasis on traditional Chinese values, including education. He was an excellent student, and has said he considered scientists Galileo and Newton to be heroes and found physics more creative than Sherlock Holmes mysteries.

He moved to the US in 1967 to study Physics at Harvard University and credits his wife, Frances Yao, with introducing him to algorithms. A former PhD student at MIT, she is now also a professor of computer science at Tsinghua.

Yao taught for nearly three decades in the US, mostly at Stanford and Princeton, before returning to China in 2004. A number of other celebrated Chinese scholars returned from abroad around the same time, including Nobel prize-winning physicist Yang Chen-Ning and biophysicist Shi Yigong.

Yao told the state-run Xinhua News Agency that the opportunity to educate young Chinese students meant it was “not a difficult decision” to make.

New understanding

Former students say Yao’s accessible and participatory teaching style helps to unlock the complex, highly abstract ideas at the heart of his discipline. He’s been known to invoke the Wizard of Oz or Alice in Wonderland when discussing his journey through computer science. Students are encouraged to answer questions on the spot and to challenge their teacher, and may be treated to KFC or Pizza Hut if a class member solves a particularly tough problem.

And the tough ones really are tough. Yao’s Millionaires’ Problem asks how two individuals can decide which of them is richer, if neither is prepared to say how much money they have. Answering such questions through cryptography—the study of secure communications techniques—has real-world applications for e-commerce, data mining, and many of the corners of the internet that call for passwords.

Within his field, Yao is perhaps best known for his work on the Min-Max Principle, a decision rule that is critical to game theory and computing.

“Professor Yao’s work gave us new ways of understanding algorithms,” said Aleks Kissinger, associate professor of quantum computing at the University of Oxford, in his introduction to a speech Yao gave in May. “The way that he explains fundamental problems is very relevant to scientists but also to anyone interested in more fundamental questions about the limits of what we can accomplish and what kinds of problems we can solve.”

In addition to his computer science class at Tsinghua, Yao has established more specialized classes in AI and quantum information. He also serves as the chief editor of China’s high-school AI textbook—a publication that was introduced in 2020.

“China missed the microelectronics revolution 70 or 80 years ago, so today it is difficult to catch up with the advanced level of the international semiconductor industry,” Yao said in an interview with China Global Television Network last year. “But in emerging fields such as quantum technology and artificial intelligence, China is expected to become an important player.”

Zou Hao, a former Yao student whose startup Tsimage Medical Technology offers AI-driven diagnosis services, believes Tsinghua graduates will play an important role in the technology’s future. “As time goes by, there will be more and more talents from Yao Class that make a difference and get great achievements,” he said.

Other entrepreneurs from the Yao Class include Li Chengtao, founder and CEO of AI drug discovery firmGalixir; Qi Zichao, co-founder and chief architect of metaverse startup DeepMirror and Long Fan, founder-president of blockchain startup Conflux. In academia, Yao alumni have been found on staff at Duke, Princeton and Stanford Universities, as well as at Tsinghua and Renmin University of China.

“Whether it’s applying for studying abroad or getting a job at universities, the label of Yao Class graduate did benefit me,” said Huang Zhiyi, an associate professor of computer science at the University of Hong Kong who was a Yao Class compatriot of Pony.ai’s Lou.

“Almost every aspect of my life and work is impacted by my experience there.”

To contact the author of this story:

Jane Zhang in Hong Kong at hzhang901@bloomberg.net