The Value of Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance: A Summary – AAF – American Action Forum

Executive Summary

Contrary to common criticisms, employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) provides significant value to beneficiaries and taxpayers far beyond the cost of the tax subsidy.

Employees value ESI at 75–84 percent more than employers and employees together pay for it, generating an annual private value of at least $800 billion.

Further, after accounting for the tax subsidy, ESI provides an annual net economic benefit to society of at least $600 billion by reducing fiscal pressures on subsidized insurance programs and encouraging work and business formation.

In total, ESI generates around $1.5 trillion annually in social value beyond what workers, employers, and taxpayers pay for it, or nearly $10,000 per insured individual.

Introduction

Employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) is the most common source of health insurance in the United States, covering around 156 million Americans in 2021.[i] Withstanding various attempts at health care reform, the employer system has remained the backbone of how the United States pays for health care and ESI enrollees highly value this coverage: According to a March 2021 survey from America’s Health Insurance Plans, more than two-thirds of ESI enrollees are satisfied with their current coverage.

Despite the endurance of ESI and high satisfaction among enrollees, many economists characterize the employer system as an anachronistic policy that is not worth the cost of its tax exemption that excludes premiums from taxable income—which, based on tax-revenue studies from the Congressional Budget Office and the White House Council of Economic Advisers, totals around $200 billion per year.[ii] This thinking neglects the substantial value generated by ESI and the cost savings unique to its group purchasing structure. Based on The Value of Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance, released by the National Bureau of Economic Research, this paper further explores the social value of ESI—the sum of private and external components—and quantifies how such value well exceeds the cost of the tax exemption.

Private Value

Private value generated by ESI accounts for the benefit that an individual or family receives from its access to health care, such as the value of being healthy, the cost-savings obtained from group purchasing agreements, and the delegation of benefit management and insurance decisions. This analysis explores the private value of ESI in two ways—first, by analyzing various components of private value and then through revealed preference estimates.

Components of Private Value

ESI is connected with individual health and the health of the workforce, which are inherently valuable. As the majority of Americans receive health care through employer-sponsored plans and employees spend many hours per week in the workplace, the value of ESI is intertwined with the value of health. Employers’ interests are aligned with improving the health outcomes of their employees given that companies with a healthier workforce are likely to see greater productivity, higher business returns, and reduced health care costs. ESI acts as a mechanism through which employers are able to act on such incentives to maintain healthy employees. This incentive is further accentuated by the tight labor market in which employers compete to attract and retain talent, leading many businesses to offer innovative benefits such as wellness programs or risk assessments designed to identify health issues and manage chronic conditions.[iii] The ability of employer health plans to successfully manage chronic disease and incentivize healthier lifestyles is a valuable element in meeting the health care needs of the American workforce. As evidenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, the connection between employment and health allows employers to play a unique role in reducing the spread of infectious diseases at the workplace, such as implementing testing procedures, improving air filtration systems, and engaging in contact-tracing strategies. Preliminary research suggests that through cooperation and scale economies, employers were able to prevent and reduce the spread of COVID-19 better than households.

Another key piece of ESI’s value comes from its ability to put downward pressure on health care costs. Providers hold market power in many health care markets, and due to constraints on competition, providers are able to sustain price increases. In this environment, however, ESI functions as a procompetitive force, leveraging the power of group purchasing agreements to obtain substantial discounts and rebates for beneficiaries. When faced with high provider prices, employer plans act like buyers’ clubs that limit the market power of providers in order to drive down prices. In a buyer’s club, such as Costco, for example, members may not have a price-elastic demand for a certain brand of a given product. When dealing with customers individually, suppliers could take advantage of this by increasing prices. Costco, however, is able to limit the number of suppliers who can sell to their members to only those offering the lowest prices. Additionally, the diversity of brand preference among Costco members is what allows group purchasing to deliver such high value; if all Costco members preferred a specific brand of a given product, rather than simply preferring the lowest-cost option, manufacturers of that brand would have little incentive to offer discounts to Costco.

Similarly, ESI plans are able to exclude higher-cost health care providers to ensure their members have access to a greater volume of high-quality, affordable health care options. The value obtained through the group purchasing structure is significant: Private insurers obtained hospital discounts of at least 40 percent and prescription drug rebates of 12 percent, based on studies from 2011 and 2016, respectively. Together, the total amount of cost savings obtained from group purchasing agreements in employer plans likely exceeds $100 billion annually. Additionally, while employer plans group beneficiaries with diverse health insurance preferences to reduce adverse selection, it is difficult to reproduce these types of cost savings in individual-market plans that often require additional expenditures on administrative costs in order to manage the distribution of risks among plan members.

Reducing consumer effort through the delegation of insurance decisions and administrative assistance is another valuable aspect of ESI that is especially advantageous for those who would have difficulty navigating the health care system on their own. Employer plans often offer administrators or insurance specialists opportunities to manage employee benefits and provide insight about new plan options or providers in ways that advance the interests of the beneficiary. Such specialization in health care decision-making has proven benefits: Research has shown that individuals make better choices about plans when relevant information has been acquired and presented to them, as is often coordinated through employer plans. Without such specialization, choice errors can add 27 percent to insurance costs, according to one study. In the context of health insurance for working-age people, that would be savings of almost $2,000 per covered life year.

Revealed Preference Estimates

Another way to estimate the private value of ESI is through a revealed preference approach, in which historical changes in the price of employer-based health insurance and the number of beneficiaries are examined to determine the decisions of market participants. Many consumers purchase health insurance even when the price of coverage increases. Further, revealed-preference estimates help quantify the monetary value of ESI by providing an idea of the private value up to which ESI “passes the market test.”

Most people value ESI coverage significantly more than they pay for it. Based on price change observations and behavior analysis, workers value their ESI coverage 75–84 percent more than they and their employer together pay for it.[iv] Based on National Health Expenditure data from 2018, this amounts to between $800–$900 billion annually in private value, which alone exceeds the cost of the ESI tax subsidy.

External Value

The employer system also generates external value, including the positive effects of ESI on work, tax revenue, and business formation, as well as the benefits that an individual or family obtains from the access other Americans have to ESI, such as a greater number of people insured and fewer people on subsidized government insurance.

The Value of Work

One of the most important work incentives is the opportunity to enjoy high-value, high-quality health coverage. Given that an individual must be working—or have a family member who works— in order to receive coverage through an employer, eliminating ESI would take away an important incentive to work. Additionally, eliminating ESI would reduce the value of future employment as each dollar spent on ESI is worth more than the value that the dollar would purchase elsewhere. In turn, this work directly generates around 80 percent of tax revenue and indirectly encourages business formation as few employers can earn a profit or pay taxes without finding the right personnel to join their workforce.

Although critics refer to the role of ESI in encouraging work as “job lock,” such arguments ignore that workers who choose to give up other things in order to retain ESI confer positive externalities to society through taxes and reduced reliance on other forms of subsidized insurance. Each year, ESI generates around $600 billion in total employer profits and tax revenue, though the exclusion of ESI premiums from payroll and income taxes reduces tax revenue by about $200 billion annually. In sum, the value of work is around $400 billion annually, net of the tax exclusion.

Several scholars have documented the harm to communities and families that results from a lack of work, such as reductions in civic engagement, higher rates of substance abuse and mental illness, and declining rates of employment and marriage. Although these factors were not accounted for in this analysis, the positive effects of work on social capital, family formation, and mental health would further increase the total value of work, which ESI supports.

Health Care Coverage

ESI is the main source of coverage for Americans, which significantly reduces the number of people who receive insurance through Affordable Care Act plans or Medicaid. Eliminating ESI would require nearly 160 million people to transition to an individual-market or a government plan or become uninsured. Assuming that 27 percent would become uninsured if ESI were eliminated, and assuming uncompensated care costs $989 annually per uninsured individual, this would cost $40 billion annually. Additionally, assuming that 73 percent of those currently covered by ESI plans would join individual-market or government plans, such subsidies would total around $200 billion annually. Notably, this estimate conservatively assumes that the average annual subsidy for such individuals taking up individual-market or government plans as the result of the elimination of ESI would be only half of that amount of the average annual subsidy in the individual market in 2019, which was $3,800 per person.[v]

In sum, the external value of ESI, including the value of work and the value of health care coverage, and accounting for the cost of the tax subsidy, is between $600–$700 billion annually.

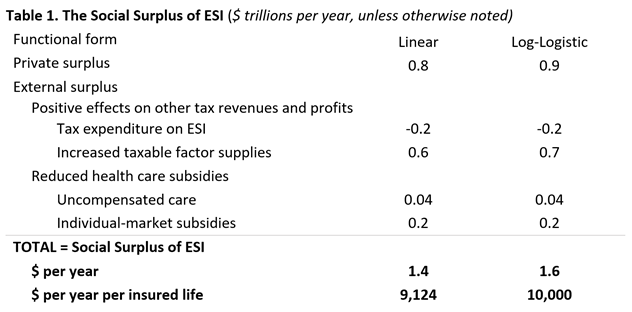

Total Social Surplus

Combining $800–$900 billion in private value and $600–$700 billion in external value net of the tax subsidy, the total social value of ESI is between $1.4–$1.6 trillion annually beyond what workers, taxpayers, and employers pay for it, as shown in the table below. This amounts to between $9,000–$10,000 in social value per covered life each year.

Conclusion

Far from being a drain on tax revenues, ESI provides some of the most significant value in the entire health care system. ESI is a procompetitive force in consolidated health care markets and alternatives to ESI often involve more public subsidies than ESI does. Ultimately, from private components, such as initiatives to improve individual and workplace health and discounts from group purchasing agreements, and external components like encouraging work, generating tax revenue and business formation, and reducing reliance on government insurance plans, ESI generates around $1.5 trillion in social value annually.

[i] https://www.ehealthinsurance.com/resources/small-business/how-many-americans-get-health-insurance-from-their-employer

[ii] https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28590/w28590.pdf

[iii] https://www.kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2021-section-12-health-screening-and-health-promotion-and-wellness-programs/

[iv] https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28590/w28590.pdf

[v] https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Deregulating-Health-Insurance-Markets-FINAL.pdf