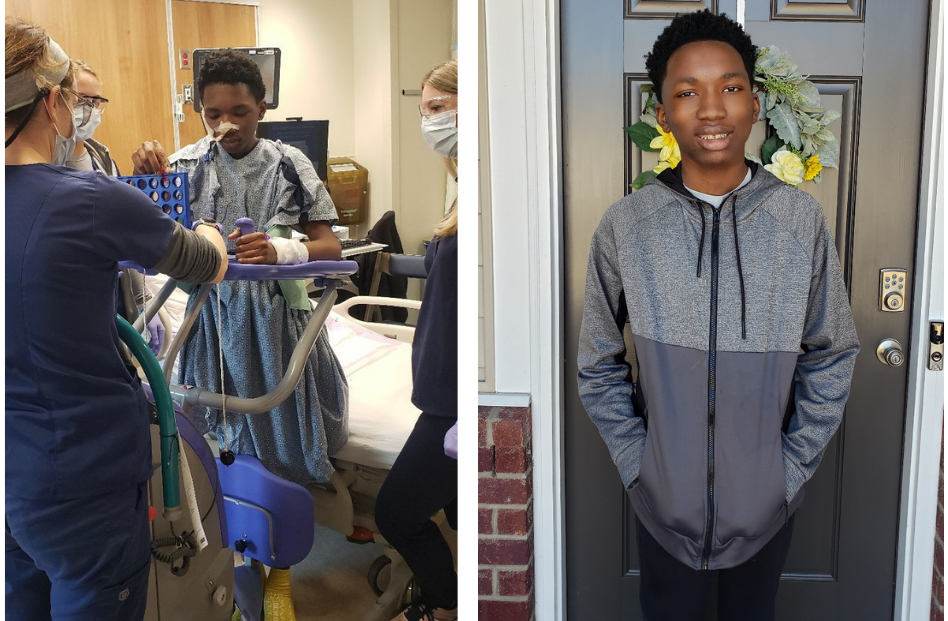

Teen makes miraculous recovery after losing the ability to walk, talk and eat

Fourteen-year-old Micah Hullum appeared to have made a full recovery 48 hours after testing positive for COVID-19. Three days later, he was lying in a hospital bed, unresponsive.

His mother, Keosha Street, suspected something was wrong when she found Micah standing in the living room, dazed and staring. He couldn’t remember why he was there. His “typical” COVID symptoms—cough, low-grade fever, dizziness—had all resolved on their own. But something still wasn’t right.

Keosha thought maybe he wasn’t getting enough sleep, or maybe his nutrition was off. But soon Micah was so fatigued and weak, he was struggling to even walk on his own. Keosha was supporting him to the bathroom and into bed. He didn’t want to eat. The brain fog had gotten worse, and he started hearing voices in the garage.

“One minute I had a perfectly health kid, and then it felt like all of a sudden, this chaos was happening,” she said. “Once these symptoms started happening, it went downhill quick.” She took him to the emergency room, where doctors said it was probably the beginning stages of schizophrenia.

Keosha, who worked as a mental health case manager before becoming a business process associate at Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina, knew that wasn’t it. Black Americans like Micah are more likely to be misdiagnosed with schizophrenia than White Americans. And it didn’t explain the other severe symptoms he was experiencing.

She decided to take him to Duke University Hospital for a second opinion. By the time they got there, Micah was nearly catatonic. He was admitted to the pediatric ward, attended to by a team of neurologists, psychiatrists and rheumatologists. When Micah first became unresponsive, it seemed like the whole hospital ran to his bedside.

“It was like a scene from one of those medical shows. There were twenty doctors in the room, and they said, ‘He’s unresponsive. We need to get a brain MRI,’” she said. “Everybody at Duke knows who my kid is. That’s the kind of case it was.”

The team of doctors diagnosed Micah with post-COVID encephalitis, or swelling on the brain. Encephalitis is a very rare complication in COVID-19 patients, and it’s especially rare in young people. Not much is known about the condition, which Keosha said made it more difficult to diagnose.

Viral encephalitis is a term that describes swelling of the brain because of a viral infection. It can happen after COVID-19 infection, but other viruses like measles and the Epstein-Barr virus can cause it, too. Encephalitis can cause neurological symptoms like weakness, lack of muscle coordination, personality changes, memory problems, and changes in hearing or speech. But case reports in the condition after SARS-CoV-2 infection are limited.

“When I went to Google, there was nobody like my kid. There was no point of reference. So I want to make sure his story gets out so that others can have that point of reference,” she said. “I can guarantee you there’s a lot of people who have been dismissed or misdiagnosed.”

By the time he was diagnosed, Micah was unable to speak, walk, or even sleep. He had no means of communicating, and he required a feeding tube for nutrition.