How to hold unvaccinated Americans accountable | TheHill – The Hill

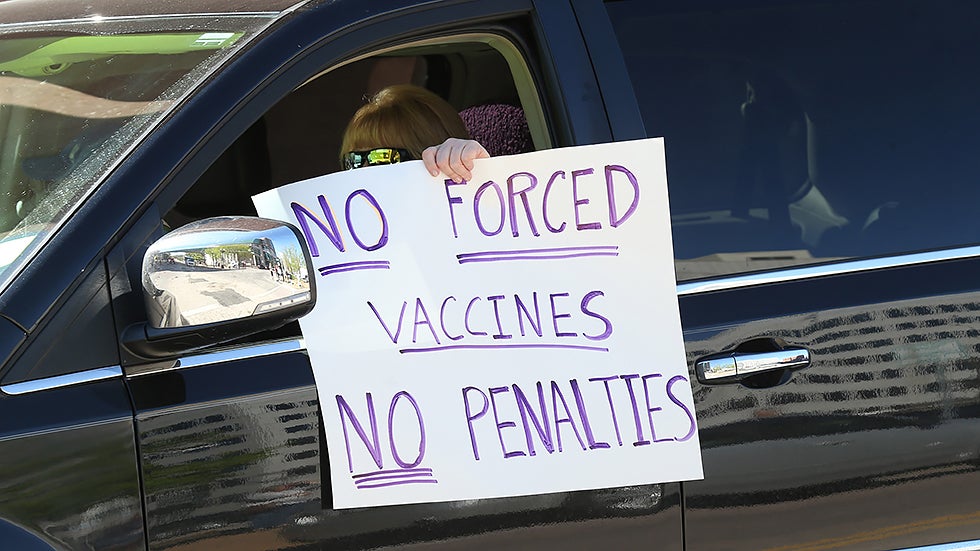

As the Omicron variant of the novel coronavirus spreads across the United States, roughly 15 percent of adults remain unvaccinated. At the greatest risk for severe illness and death, they have already overwhelmed hospitals and intensive care units in many areas of the country, reducing services available to people who have non-COVID related medical issues. Nearly 90 percent of these unvaccinated people indicate they will not change their minds. And a number of governors, most notably Ron DeSantisRon DeSantisEx-Trump official: Former president ‘failed to meet the moment’ on Jan. 6 DeSantis: Jan. 6 is ‘Christmas’ for mainstream media Florida sending 1 million free COVID-19 tests to elderly communities MORE (R-Fla.) and Greg Abbott Greg AbbottThe Hill’s Morning Report – Presented by Altria – Democrats eye same plays hoping for better results Overnight Defense & National Security — Sailors prevail in vaccine mandate challenge Abbott to sue Biden administration over vaccine mandate for National Guard MORE (R-Texas), are fighting the Biden administration vaccine mandates and thwarting vaccination requirements by schools and private employers in their states.

Greg AbbottThe Hill’s Morning Report – Presented by Altria – Democrats eye same plays hoping for better results Overnight Defense & National Security — Sailors prevail in vaccine mandate challenge Abbott to sue Biden administration over vaccine mandate for National Guard MORE (R-Texas), are fighting the Biden administration vaccine mandates and thwarting vaccination requirements by schools and private employers in their states.

“I think we’ve sort of run out of options,” Dr. Anthony Fauci Anthony FauciUK officials decide against fourth COVID-19 vaccine dose Overnight Health Care — Presented by AstraZeneca and Friends of Cancer Research — Former advisers urge Biden to revise strategy US sees record COVID-19 pediatric hospital admissions on Wednesday MORE recently declared.

Anthony FauciUK officials decide against fourth COVID-19 vaccine dose Overnight Health Care — Presented by AstraZeneca and Friends of Cancer Research — Former advisers urge Biden to revise strategy US sees record COVID-19 pediatric hospital admissions on Wednesday MORE recently declared.

Fauci’s frustration is understandable. But there is one way to hold unvaccinated Americans accountable for putting themselves and others at risk: make them pay more for health insurance through surcharges and eliminating paid time off when they are sick, while offering financial incentives (including lower deductibles) for fully-vaccinated Americans who enroll in wellness programs.

There is ample precedent for doing so. Smoking is exempted from federal laws restricting discrimination in premiums based on health status. Insurance companies can place a surcharge up to 50 percent (subject to limitations imposed by states) for anyone who uses a tobacco product four or more times per week. Carriers rely on the honor system, but misrepresentation constitutes fraud, and in some states is a felony. Employers providing health insurance often require routine medical examinations, in which nicotine can be detected through samples of blood and urine.

And many driving infractions result in substantial increases in automobile insurance rates: driving under the influence (DUI) can raise rate 65.5 percent; refusal to submit to a chemical test, 63.5 percent; reckless driving, 61.1 percent; at-fault accidents resulting in more than $2,000 in damages, 45.2 percent; passing a school bus, 28.4 percent; speeding, 23.8 percent; failure to stop at a red light, 22.6 percent; texting while driving, 21.6 percent; failure to use a seat belt, 5.6 percent.

This fall some employers began requiring unvaccinated workers to pay more for their health insurance. Delta Airlines (which, on average, has been paying $50,000 for each COVID-related hospital stay) imposes a surcharge of $200 per month for its unvaccinated staff. Delta also limits salary protection for those who miss work to workers who have been vaccinated and have had “breakthrough” infections. Since these policies took effect on Nov. 1, 2021, it’s worth noting, the vaccination rate among Delta employees has risen to 94 percent.

Mercy Health, whose 7,000 employees work in hospitals and clinics in Wisconsin and Illinois, has introduced a “risk pool fee,” in which $60 per week is deducted from the wages of workers who have not been vaccinated. After the policy was announced in September, vaccination rates rose from 70 percent to 91 percent.

As Omicron rages, health care workers are exhausted, frustrated, and disheartened. In a sentiment shared by many of her colleagues, Sarah Rauner, a chief nurse practitioner in Troy, Mich., declared, “So much of what we see on a daily basis is preventable.” A few days before Christmas, Sue Wolfe, a nurse in Madison, Wis., wondered why unvaccinated people “did this, why are they doing this to me … This is my second 16-hour shift this week. Came in at 2 o’clock in the morning and it’s now 7 at night. I got my 20-minute break. It gets hard. I am 61 years old and I am doing this.” Wolfe pleads with the unvaccinated to get vaccinated: “Do it for the people that you care about, that perhaps are susceptible to getting really sick because of the virus that you’re carrying.”

Last summer, an exasperated Gov. Kay Ivey Kay IveyAlabama to invest M to train students for tourism workforce Governors grapple with vaccine mandates ahead of midterms On The Trail: Trump-inspired challengers target GOP governors MORE (R-Ala.) told reporters, “Folks are supposed to have common sense. But it’s time to start blaming the unvaccinated folks, the regular folks. It’s the unvaccinated folks that are letting us down.”

Kay IveyAlabama to invest M to train students for tourism workforce Governors grapple with vaccine mandates ahead of midterms On The Trail: Trump-inspired challengers target GOP governors MORE (R-Ala.) told reporters, “Folks are supposed to have common sense. But it’s time to start blaming the unvaccinated folks, the regular folks. It’s the unvaccinated folks that are letting us down.”

Two-thirds of Americans now say they are angry at the unvaccinated.

Two years into a pandemic that has claimed over 800,000 lives, blaming and shaming are unlikely to persuade the vast majority of those remaining to take a safe and effective vaccine, for themselves, people they care about, or strangers they encounter in grocery stores or restaurants.

But if the unvaccinated can’t be reached through their hearts or minds, we can — and should — require them to pay at least some of the financial costs they are forcing the rest of us to bear.

Glenn C. Altschuler is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Professor of American Studies at Cornell University. He is the co-author (with Stuart Blumin) of “Rude Republic: Americans and Their Politics in the Nineteenth Century.”