Health Care Sharing Ministry Data Point to Problems for Consumers, Regulators

By Nadia Stovicek and JoAnn Volk

A recent study from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) sheds new light on health care sharing ministries (HCSMs). The GAO interviewed officials from five HCSMs on plan features, enrollment, and marketing. The report includes, for example, information about HCSM use of paid sales representatives, administrative costs (one HCSM directs up to 40 percent of members’ contributions to administrative costs) and membership (one HCSM said a survey of their members found 42 percent had income under 200 percent of the poverty level, which would make them eligible for substantial subsidies for a Marketplace plan). But the report offers only a snapshot of a handful of HCSMs.

Despite a history of fraud and unpaid bills, HCSMs are largely a black box for insurance regulators and the general public. Trinity, an HCSM administered by the company Aliera, recently went bankrupt; at least 14 states have taken action to shut down Aliera because of their malfeasance. Members suing Aliera are only expected to recoup one to five percent of the money they are owed, which can amount to hundreds of thousands of dollars. More recently, the North Dakota Attorney General settled a lawsuit with HCSM Jericho Share for creating “a false impression that its products are health insurance” and using that false impression to sell memberships. Beyond the data in the GAO report, little is known about the operations or finances of HCSMs. A consumer considering becoming a member of a health care sharing ministry—with an expectation that their health care bills will be paid—may want to know, for example, if the HCSM has a history of stable revenue or keeps in reserve enough funds to cover members’ health care bills. To better understand what information is available, we reviewed publicly available audits and revenue reports to the IRS to see what information an ambitious consumer could obtain about an HCSM before enrolling.

What are HCSMs?

HCSMs’ members agree to follow a common set of religious or ethical beliefs and contribute regular payments to help pay the qualifying medical expenses of other members. HCSMs have many features that are similar to those of insurance. For example, members’ payments are typically required on a monthly basis and may vary depending on age and level of coverage, much like a premium. Members must pay some costs out-of-pocket before they can submit bills to the HCSM for payment, akin to a deductible; member guidelines for coverage often require members to pay co-insurance and use a network provider when getting care. Even the marketing relies heavily on the similarity to insurance, which can mislead consumers into thinking they’re getting more from a membership than an HCSM provides.

Despite these similarities, most states do not consider HCSMs to be health insurance issuers, and do not subject them to the standards that insurance companies must meet. This can leave members financially vulnerable. HCSMs make no guarantee that they will cover any health care claim, even those that meet guidelines for sharing, and they don’t have to meet financial standards to ensure they have enough funds to pay claims. They also do not have to comply with the consumer protections of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). For example, HCSMs do not have to cover essential health benefits, which include hospitalization, maternity care, mental health and substance use disorder services, prescription drugs, and preventative services. In fact, HCSMs typically exclude coverage for preexisting conditions, behavioral health, and maternity care except in limited circumstances, and limit coverage for prescription drugs.

What data is publicly available?

State regulators need data to understand how HCSMs operate and market memberships to consumers, but most states don’t collect such information. Only Colorado requires data from all HCSMs selling memberships in-state; Massachusetts collects data from those HCSMs whose members can claim credit for coverage under the state’s individual coverage requirement. The federal government doesn’t collect or provide to the public actionable data about HCSMs either.

However, some states require HCSMs that seek an exemption from state insurance requirements to make available an annual audit upon request. The ACA definition of HCSMs whose members are exempt from the individual mandate also includes that requirement. Based on these annual audit reporting requirements, we contacted seven HCSMs, representing the largest HCSMs operating across states to request a copy of their annual audit: Altrua, Christian Healthcare Ministries (CHM), Medi-share, Samaritan, Sedera Health, Solidarity, and Liberty HealthShare.

These audits are typically performed by an accounting firm and provide an overview of the financial solvency of an organization, including statements of financial positions, activities, functional expenses, and cash flows. Of the 7 HCSMs we contacted, only 3 provided us with an audit when asked. (See Table 1.) One HCSM, Medi-Share, only provided a brief document with more limited data than would be required in an official audit.

Table 1.

HSCMAudit provided?AltruaNoChristian Healthcare MinistriesYesMedi-Share Christian Care MinistryNoSamaritan MinistriesYesSedera HealthNoSolidarity HealthShareNoLiberty HealthShareYes

Source: Authors’ communication with the listed ministries

Because we were unable to obtain an annual audit from all seven HCSMs, we also reviewed their publicly available 990 forms to analyze financial data. Non-profit organizations must annually file a Form 990 with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). With this form, non-profits report required data on the organization’s activities, finances, governance, and compensation paid to certain employees and individuals in leadership positions. We obtained multiple years of 990 forms through ProPublica, a news site, and the IRS website for all of the HCSMs we reviewed except Sedera. It’s unclear why Sedera, which claims to be a non-profit on its website, would not have submitted a 990. Because the IRS has not yet published 2021-2022 990s, we could not review the most recent data.

What the Data Reveal

Audits, where available, provide greater detail than a 990. For example, audits provide information on “functional expenses,” which include spending on public relations, employee benefits and taxes, among other expenses. Two audits also reported loans received under the Paycheck Protection Program: $3 million to Liberty HealthShare and $2.5 million to Christian Healthcare Ministries, both of which were forgiven.

But audit data aren’t reported in a consistent way. For example, Samaritan Ministries and Christian Healthcare Ministries list members’ gifts and dues as revenue; Liberty HealthShare does not count member contributions as revenue because they are held in members’ sharing accounts, which are not reflected in the audit. In another example, Samaritan Ministries reports spending on advertising, Christian Healthcare Ministries reports spending on “member development fees,” which is said to reflect spending on advertising, and Liberty HealthShare reports “member development fees” and “advertising” costs separately, which suggests member development fees may include commissions to brokers. HCSMs that pay broker commissions often pay substantially higher commissions than those paid to brokers who enroll people in ACA coverage, which can drive greater enrollment.

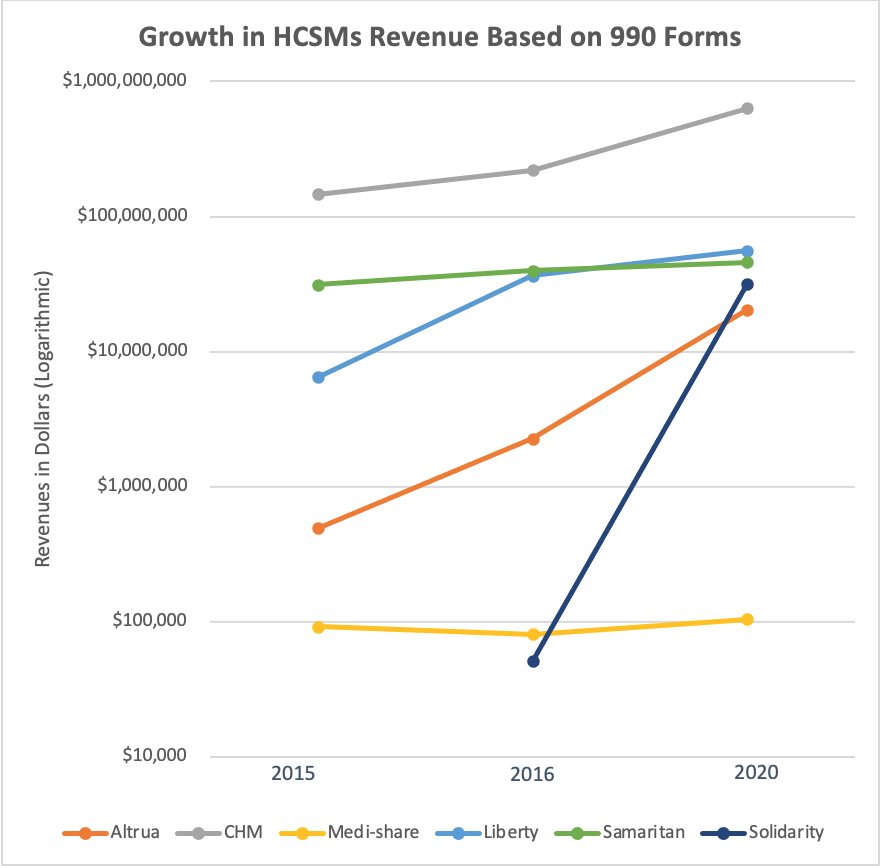

Because we were able to obtain multiple years of 990s, we were able to compare revenue changes over time. HCSMs report total revenue on 990s based on contributions, program services, or both. The 990s lack detail but it’s likely the revenue at least roughly reflects growing membership. Most HCSMs’ 990s that we reviewed saw huge revenue growth between the years we could review. (See Graph 1). For example, Solidarity HealthShare’s reported revenue grew a whopping 62,143% in four years, and Altrua grew about 4,010% in five years. Medi-Share was a notable exception to this trend; it reported very little revenue and growth between 2011 and 2020. It’s not clear why, as Medi-Share is one of the oldest and largest HCSMs in the country.

Graph 1.

Source: authors’ analysis of 990 filings

A majority of the HCSM 990 forms we reviewed (Solidarity, Samaritan, Christian Healthcare Ministries, Medi-share, and Altrua) indicated spending in excess of revenues in some years and substantial revenue fluctuations year-to-year. This raises questions about the adequacy and stability of funding available to cover members’ health care costs. One HCSM, Liberty HealthShare, has come under recent scrutiny for their history of not paying their members’ claims.

One challenge with the data available on the 990s is that each HCSM reports its data differently, making it difficult to make comparisons between them. In contrast, health insurers must use a standardized template to report financial data to state regulators, making it possible to understand and compare insurers based on premium revenue, available reserves, and expenses paid for administrative costs and members’ health care claims.

Conclusion

The dramatic growth in revenue for the majority of HCSMs we looked at suggests substantial growth in enrollment. However, the significant revenue fluctuations from year-to-year, coupled with some HCSMs showing expenses that exceed revenues, raise questions about whether consumers who choose an HCSM as an alternative to comprehensive coverage can count on their health care bills getting paid. Regulators seeking to understand the growing role of HCSMs in their markets—and the risks to consumers who are persuaded, often by misleading marketing, to buy memberships—need more complete data reported on a regular basis. Ensuring HCSMs comply with the requirement to make available an annual audit is a place to start in states where that applies, but even that data is limited and all states should have an interest in obtaining more complete data to better understand this growing segment of coverage.