CHIR Expert Testifies About Facility Fees Before Texas House Insurance Committee

In early September, CHIR Assistant Research Professor Christine Monahan testified before the Texas House Insurance Committee on outpatient facility fee billing and potential reforms. The Texas legislature is currently preparing for its 89th legislative session next spring, and the recent hearing will play a critical role in shaping legislation to come.

Christine’s comments to the committee follow. A corresponding slide deck is available here.

At CHIR, we study private health insurance and health care markets, conduct legal and policy analysis, and provide technical assistance to federal and state policymakers, regulators and stakeholders on a range of topics. With the support of West Health, I and several members of the CHIR team have been studying outpatient facility fee billing for the past two years. We have conducted several dozen interviews with on the ground stakeholders, reviewed existing laws and pending legislation at both the state and federal levels, written multiple analyses, and, most recently, published a suite of maps reporting on our review of the laws in all 50 states and the District of Columbia related to outpatient facility fee billing.

The first step to understanding facility fee billing is to understand that there are two types of claims typically used to bill for medical services: a professional bill (the CMS-1500) and the facility bill (the UB-04). If you receive care at an independent provider practice, the provider who treated you will submit a professional bill to your insurer. This bill, in theory, covers their time and labor as well as any practice overhead costs, like nursing staff, rent, and equipment and supplies. On the other hand, if you receive care at a hospital outpatient department, generally speaking any professional who treated you, as well as the hospital, will each submit separate bills. Any professional bills should just cover the provider’s time and labor, while the hospital bill – or facility fee – ostensibly covers overhead costs.

What counts as hospital overhead and what else goes into a facility fee is complicated, however. As you would expect, a facility fee generally will cover the overhead costs related to the patient visit for which it is being billed, including the nurses or support staff involved and any equipment and supplies. Because hospital outpatient departments need to meet extra licensure and regulatory requirements, they likely also have some additional costs that do not apply to independent settings.

In addition, a facility fee is likely to cover other hospital overhead costs. Some of these are necessary and desirable services at the population level, but not related to the care delivered to the patient who is getting billed. For example, facility fees might help fund things like hospital emergency services, or 24/7 staffing and security at the hospital, even though the patient was at the facility during normal business hours and didn’t need any emergency care or they went to a totally separate, off-campus facility ten miles from the hospital campus and emergency room. Hospital overhead costs can also include things of more debatable value – from high CEO salaries, to expensive artwork or gourmet food services, to, I kid you not, movie production studios. All of these things may be considered hospital “costs” that patients can be asked to pay through a facility fee.

It is also important to know that other factors, unrelated to the cost of care or other expenses a hospital has, also play a big role in determining how much a hospital bills for and gets paid by insurers, including historical billing patterns and market power. Particularly as hospitals and health systems get bigger, and vertically integrate, they have much more power than your solo physician or independent group practice to demand higher reimbursement when negotiating with insurers.

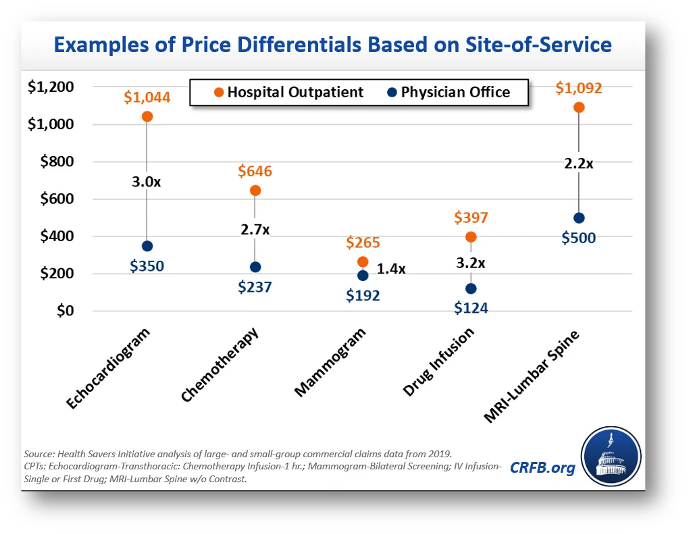

So, when economic experts compare the prices paid for the same services at hospital outpatient departments and independent physician offices, they find much higher prices in hospital settings. Chemotherapy is one example from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. A patient going for weekly chemotherapy visits would see, on average, a 2.7-fold difference in price if they switched from an independent practice to a hospital outpatient department. And, of course, they’re often not the ones making that choice to switch – rather, one day in the middle of treatment they may go into the same office building as always, for the same care as always, and come away with a bill that’s more than $400 higher than what they’re used to because a hospital acquired their practice and converted it to a hospital outpatient department.

It is this recent history of aggressive hospital acquisition of outpatient practices that is driving the issue today. Facility fee billing is not a novel practice, but it is more common than it used to be following years of vertical integration where hospitals are acquiring or building their own outpatient physician practices and clinics. Indeed, one of the reasons hospitals and health systems have significantly expanded their ownership and control over outpatient physician practices over the past decade or so, is so they could charge this second bill and increase their revenues.

Another likely reason we are hearing about facility fee billing more now are inadequacies in insurance coverage. As the hospital industry will emphasize, patients increasingly are coming in with high deductible health plans which leave them exposed to more charges, including facility fees. The hospitals are not wrong in pointing out this gap, but it is best understood as a symptom of the greater problem of rising prices.

Higher spending on outpatient care from facility fee charges is increasing the cost of health insurance for all of us: patients and consumers who enroll in health insurance, employers who are sponsoring insurance for their workers and paying more than 70-80% of their health plan premiums, and taxpayers who heavily subsidize the private health insurance market. Economist Stephen Parente, who served on the White House Council of Economic Advisers in the Trump Administration, recently released a study finding that employer plan premiums could go down more than 5% annually if insurers paid the same amount for care in a hospital outpatient department as they do an independent physician’s office. This in turn would result in $140 billion in savings to the federal government over ten years through reduced tax subsidies for employer plans. While not the only factor, outpatient facility fee billing is contributing to the growing unaffordability of health insurance today.

At the same time, insurers are responding to these price increases largely by increasing cost-sharing and otherwise limiting benefits. As the hospital industry points out, health insurance deductibles are increasing in size and prevalence. Many of those $200, $300, $400+ facility fees are going straight to the patient. Consumers also can face higher cost-sharing for care provided at a hospital outpatient department even when their deductible doesn’t apply. This can be because the facility fee is carrying its own distinct cost-sharing obligation from the professional bill or because insurers set higher cost-sharing rates for services provided at hospital outpatient departments to try to discourage patients from going to them. Additionally, some insurers may simply not cover a service when it is provided at a hospital outpatient department, in an effort to contain their own spending while potentially opening up patients to balance billing.

In sum, inadequacies in insurance coverage are playing a role in exposing consumers to high medical bills which is driving media attention. But if insurance covered these charges without any cost-sharing, consumers as well as employers and taxpayers would still be paying for it through their premium dollars – it just would be less visible.

What, then, can be done to address these concerns? One option is to continue to wait to see if the private market will fix it. But there are barriers to private reforms, including a lack of information, a lack of leverage, and a lack of motivation.

With respect to information, one of the refrains we consistently hear from stakeholders is that there are significant gaps in claims data that make it challenging for private payers and regulators alike to understand the full scope and impact of facility fee billing. Specifically, they reported that it can be very difficult if not impossible to identify the actual brick and mortar location where care was provided on a claims form or in a claims database. The address line may just refer to the main campus of a hospital that owns the practice, or even an out-of-state billing office for the health system.

In terms of leverage, dominant hospitals frequently have the upper-hand in negotiations with insurance companies as a key selling point for insurers is that they have the name brand hospital or physician group in their network. In Massachusetts, one of the major insurers proactively sought to eliminate outpatient facility fee billing by in-network providers, but could only do this in a budget neutral manner (agreeing to raise rates elsewhere to make up the difference) and still one major health system has refused to play ball and continues to bill facility fees today. Reforms like prohibiting anticompetitive contracting clauses, as Texas has enacted, may begin to chip away at factors contributing to hospitals’ dominance in negotiations however.

Regarding motivation, insurers generally don’t benefit from lowering health care costs as they take home a percentage of spending. But public scrutiny on egregious facility fees in Massachusetts motivated the insurer I previously mentioned to act, and could encourage other insurers elsewhere to follow suit. Additionally, large employers increasingly are engaging on this and other health care spending issues, and they may be able to pressure insurers to eliminate facility fee billing in their contracts with providers. Indeed, I know of at least two state employee health plans that have done so.

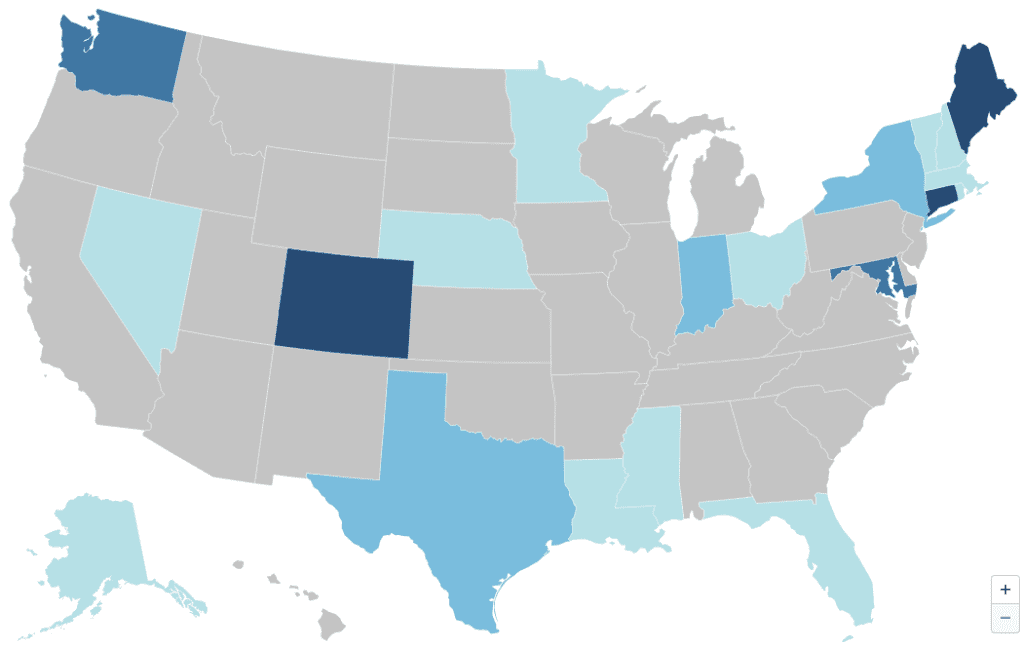

Ultimately, though, facility fee billing and other aggressive hospital pricing and billing practices are an uphill battle for the private market to tackle alone. Accordingly, we are seeing states across the country, reflecting broad geographic and political diversity, begin to pursue legislative reforms. By our count, twenty states nationwide have enacted one or more of the six potential solutions our team has identified: site neutral payment reforms, facility fee billing bans, billing transparency requirements, public reporting requirements, cost-sharing protections, and consumer notification requirements. I’m going to focus on just the first three I mentioned right now, but we have additional information on others and I’m happy to discuss any of them. Importantly, none of these reforms are mutually exclusive. They simply tackle the issues from different, but complementary angles.

First, states are beginning to tackle the transparency issues I just raised. Notably Colorado, Nebraska, and Nevada now require off-campus hospital outpatient departments to acquire a unique, location-specific provider identifier number – known as an NPI – and include it on claims forms. This is a simple and minimally burdensome reform that would greatly enhance claims data. As Colorado has learned, pairing this data with a system for tracking which NPI belongs to which health system can make it even more useful, as it would give visibility into both the location of care and who owns that setting. This information could help private payers or regulators and policymakers rein in outpatient facility fee billing. It also could be valuable in helping payers adopt tiered provider networks or otherwise steer patients towards or away from different provider locations based on the quality or cost of care they provide.

A state seeking to go further than that could prohibit hospital outpatient departments from charging facility fees for specified services. Texas, of course, has already done this very narrowly for services like Covid-19 tests and vaccinations when performed at drive-through clinics at free-standing emergency departments. States like Connecticut, Maine, and Indiana, however, have more broadly prohibited hospitals and health systems from charging facility fees for outpatient evaluation and management services or other office-based care in certain settings.

By prohibiting facility fees for specified services, policymakers protect patients from potentially bearing the cost-sharing brunt of two bills. For example, rather than owing a $30 copay on the physician’s bill and a 40% coinsurance charge on the facility fee, the patient will go back to owing just a $30 copay, as if they had received care in an independent setting. For the large percentage of the population who do not have enough cash to pay typical private plan cost-sharing amounts, this is a really big deal. At the same time, the system-wide savings from such a reform likely will be relatively muted in the longer term, as market powerful hospitals renegotiate their contracts and increase other prices to make up for the loss of revenue from facility fees, as we saw happen in Massachusetts.

Finally, policymakers who are feeling particularly ambitious may want to consider site-neutral payment reforms, which is what Stephen Parente was studying. These reforms call for insurers to pay the same amount for the same service, regardless of whether the service was provided at a hospital outpatient department or an independent practice.

How this works, and how big of an effect it would have, depend on a number of design decisions. As with facility fee bans, one of the critical choices will be what services are covered and this could be broad or narrow. Just as important is who determines how much insurers pay for a service and how this payment level compares to existing prices. Under the most hands-off version of a site-neutral policy, lawmakers could simply require that insurers adopt site-neutral payments without specifying a payment level and leaving that to private market negotiations. Alternatively, lawmakers could identify, or task regulators with identifying, a benchmark level be it tied to existing commercial rates or a public fee schedule, such as a percentage of Medicare. The more services covered and the lower the payment level, the greater the savings.

No state at this point has enacted a site-neutral policy in the commercial sector to date, but there is growing interest and I anticipate that we will see some site-neutral bills introduced in the coming year.

Thank you for having me.