A Mental Health Specialist is Helping Underserved Moms Find Their Way – Penn Medicine

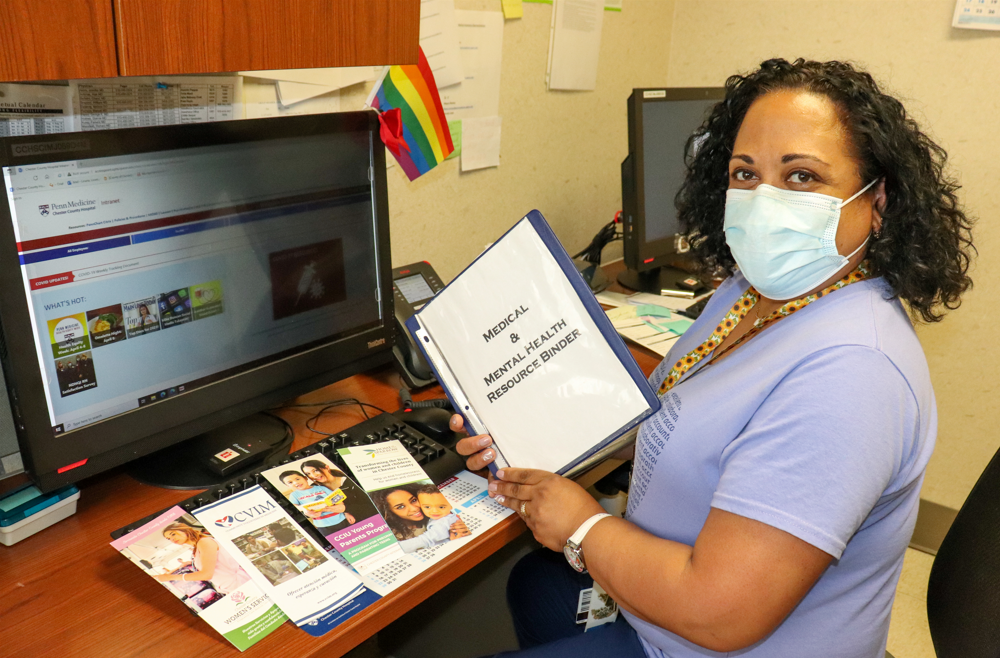

Lissette “Mitzy” Liriano, MS, BSN, RN, spends a lot of time holding hands, she says. As Chester County Hospital’s first, and only, maternal mental health specialist Liriano spends nearly all her time at the hospital working in its Ob/Gyn clinic, which offers reduced-rate gynecological and prenatal care and childbirth deliveries to ensure access to such services for patients without health insurance.

The pandemic brought a flood of new patients to the clinic, Liriano says. The recent closure of two other hospitals in Chester County has brought another wave, and many of these patients have mental health concerns, according to Liriano, who started working at the hospital in 2015 as a childbirth and breastfeeding educator. She began dividing her shifts among the hospital and clinic the next year and was appointed maternal mental health specialist in February 2018. Liriano says the position was established to help meet a growing need at the hospital, particularly in the clinic, where a majority of patients are Hispanic. She estimates at least three in five of these patients are struggling with their mental health.

“I’m seeing anxiety, depression, and perinatal and postpartum mood disorders. Many are victims of physical or sexual abuse, either currently or when they were children,” Liriano says.

Additionally, some patients who are immigrants also express feelings of guilt over children they left behind in their native countries and experience trauma related to their immigration experience, she says, as well as the ongoing stress that many people feel about making ends meet and feeding their families.

Liriano says the clinic is often their first exposure to medical care of any kind, let alone mental health therapy, which is stigmatized among many Hispanic cultures.

“Many of these patients aren’t able to, or won’t, get the help they need, so their suffering becomes this constant pain that follows them everywhere and gets bigger and bigger,” Liriano says. “Even if they do manage to bring it up to a provider or nurse, where do they begin? In the best-case scenario, they’re experiencing a situational depression that will hopefully improve. But many have been carrying this baggage for years and simply have no way to separate themselves from it.”

Liriano works closely with a number of local agencies, including, but not limited to, the Chester County Department of Health’s Nurse-Family Partnership, the Chester County Maternal and Child Health Consortium, and West Chester University Community Mental Health Services, to help her patients find long-term care and other valuable resources, like assistance with signing up for health insurance.

Reading faces and looking for clues

Liriano says she knew from the beginning of her nursing career that she wanted to help care for patients on an even deeper level. She earned a master’s in psychology with a focus on child and adolescent development and sought additional education as a mental health specialist through Postpartum Support International.

She sees Penn Medicine as the outlier because its leaders and providers appreciate the value of tending to their patients’ mental and emotional health. Maternal mental health isn’t a new specialty, she says, so much as it’s overlooked and underfunded. Across Penn Medicine, hospitals and care teams have been making concerted efforts to improve maternal health outcomes and reduce racial and ethnic disparities with a system-wide, multi-pronged approach that encompasses research, clinical care, and community engagement. Having experts to specialize in maternal mental health supports that larger goal.

As such a specialist, she might help expecting or new parents schedule appointments with a licensed professional counselor if they are intimidated by the prospect of doing it themselves because English isn’t their native language, or if they don’t have health insurance. She also calls all her patients to ask if they went to their first appointment and how it went.

Every patient of Liriano’s who is referred to a therapist is scheduled for a follow-up at the clinic a few weeks later so Liriano and the clinic’s certified registered nurse practitioner can reassess their mental health. If she finds signs of suicidal ideation, she refers the patient to the hospital’s emergency department.

“I am able to perform my duties as an RN and as a mental health specialist, only because of the help of my fellow coworkers and providers,” Liriano adds. “The whole team works together to listen, be our patients’ voice, and provide the best care and support available to them.”

Liriano says she “has a knack for reading faces.” But then COVID-19 hit, and masks made it difficult to read expressions. Ever since, she’s homed in on her patients’ eyes. “We’re very close with our patients. We get to know them well,” she says. “Subtle changes in their behavior can help us see if there’s more going on than they’re telling us.” Some are struggling in obvious ways or are unable to hide highly visible bruises and scars. For most, though, Liriano needs to listen and look carefully to identify who needs her help.

‘Each parent has their own story’

Since 2018, Liriano has led a support group at Chester County Hospital called Moms Supporting Moms, which meets on the second Thursday of each month. Attendance has grown a little with each new meeting as the group develops a following, and the regulars tell their friends to come. “Bring your baby if you have to,” they say. With the onset of the pandemic, Liriano moved the group’s meetings online.

She is armed with discussion topics — spotting the signs of anxiety and depression, how to ask for help — but she prefers to empower the parents in attendance to dictate the course of the sessions.

“I’ve been trying to tailor the meetings to the specific needs of those who attend,” she says. “Each participant has their own individual story. Some, for example, really struggle with the guilt of taking an hour for themselves when there are 110 other things they could be doing. Others are trying to figure out how to feel less inadequate and sad while being a parent to multiple children and working full time.”

Liriano has learned through her work at the clinic that finding a place to begin is often enough to help most patients regain their footing. The most natural place to start with the participants in the support group is by enabling them to give voice to everything that’s scaring them, stressing them, and frustrating them. No concern is too large or too small. By doing so, Liriano can hear them. And suddenly, they’re no longer alone.