How much did vehicles improve in the front NHTSA crash test when a passenger airbag was added?

Recently, I analyzed crash test results for 44 vehicles tested by NHTSA and came to the conclusion that a driver airbag, even a first-generation one, was a substantial safety benefit. But what about the then-more controversial passenger airbag? How much did these first-generation passenger airbags help?

This analysis included 34 vehicle models tested by NHTSA both with and without passenger airbags. Just like the driver airbag analysis, only models that were not redesigned were included; in other words, they had to be structurally identical.

As it turns out, early passenger airbags proved to be far less effective than their driver-side counterparts at reducing injury risk, offering only a modest safety advantage in this type of crash. Average passenger severe injury risks dropped only from 22% to 19%. In absolute terms, this 3% drop pales in comparison to the 12% for the driver airbag – and in relative terms, it does little better with a 14% drop, compared to 40% for the driver airbag.

Severe injury risks dropped in 20 of the vehicles tested, but rose in the 14 remaining vehicles. Just one vehicle saw an improvement of at least 20%, but improvements of 10-19% were seen in 9 vehicles. On the flip side of the equation, 5 vehicles saw their performance worsen by at least 10%, though in no cases did this reach a 20% worsening.

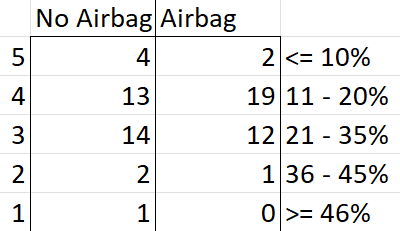

Without a passenger airbag, 31 out of 34 vehicles “passed” the test, as defined by earning at least 3 stars out of 5 for the passenger. With the bag, 33 out of 34 vehicles “passed”. Even if you look at vehicles that did well (4 or 5 stars), 17 met this criteria without the bag, 21 with it. And, while the numbers were small in both groups, fewer vehicles earned a top 5-star rating with a passenger airbag than without.

Star ratings confirm only modest improvement with early passenger airbags versus without them.

Just like with driver airbags, passenger airbags showed more of a benefit with trucks, vans, and SUVs than with passenger cars. Average severe injury risks technically rose for passenger cars, from 17% to 19%. However, due to the small sample size (16 models), this result is not statistically significant and it would be more accurate to say that average risks stagnated. 7 of the passenger cars saw improvement, while 9 saw worsening.

Trucks, vans, and SUVs saw some improvement, with average severe injury risk dropping from 26% to 18%. 13 of them improved, while 5 worsened.

Just like with driver airbags, the improvements were exclusively to head injury risk. On average, the HICs dropped from 808 to 603, a 25% drop. Chest G’s, however, worsened from 48.1 to 52.0, an 8% rise. This suggests a somewhat significant drop in head injury risk in exchange for a slight rise in chest injury risk, or, overall, a modest drop in overall injury risk.

For passenger cars, average HICs dropped from 741 to 637 (14%), while chest G’s rose from 44.9 to 51.1 (also 14%), in effect trading a slightly reduced risk of head injury for a slightly increased risk of chest injury instead. In trucks, vans, and SUVs, average HICs dropped from 868 to 572 (34%), while chest G’s rose slightly from 51.0 to 52.8 (4%), a negligible increase.

Simple physics helps explain the limited effectiveness of these early passenger airbags. The passenger is typically about twice as far from the dashboard (20-24 inches) as the driver is from the steering wheel (11-13 inches) in this test, since both seats are in their mid-track position. This means that, as long as the vehicle structure holds up, it’s possible to design a seat belt system that can prevent hard head contact by itself. Many early passenger airbags were so aggressive and/or firmly inflated that in a crash of this severity, they were no better than not having one. The trucks, vans, and SUVs tested were on average 2 years newer than the passenger cars due to these types of vehicles typically receiving airbags later; as airbag aggressivity dropped with later designs, this may be one of the reasons for these vehicles’ more favorable performance.

For equal measured injury risks, you’re typically better off with a driver airbag than without. This holds true for passenger airbags as well, albeit to a lesser extent, as a seat belt alone can prevent hard contact in this type of crash for a passenger, whereas a driver’s head will nearly always contact something hard, typically the steering wheel, without an airbag.

And, of course, this post is not meant to state that passenger airbags are almost useless. Depowered passenger airbags, which came out starting in 1998, were more effective while being far less dangerous to vulnerable occupants. Carmakers learned to optimize their seat belt and passenger airbag designs to reach levels of protection that would have never been possible without the bags, both in the NHTSA test and in a wide range of other types of crashes. Despite their rocky start, passenger airbags have come a long way in about 30 years.