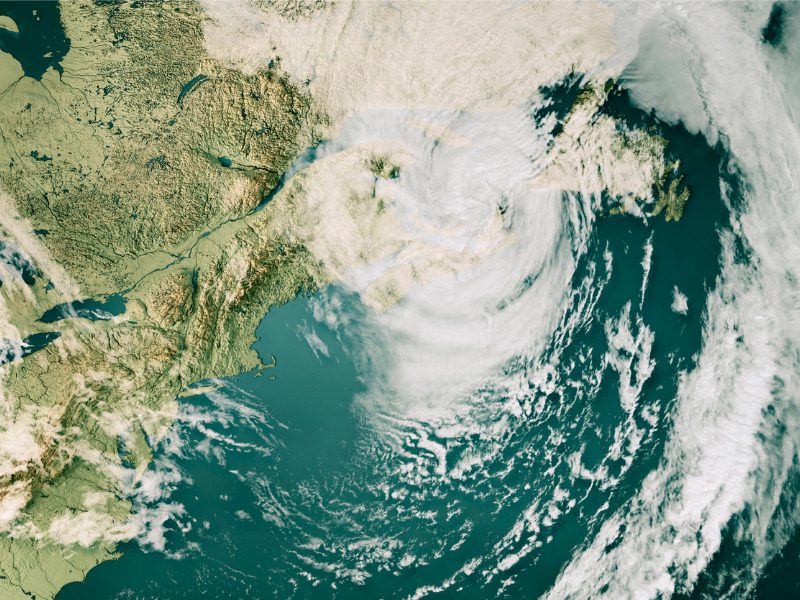

Do we need a Category 6 for hurricanes?

Two climate scientists are questioning whether the open-endedness of Category 5 hurricanes is sufficient to communicate the risk of hurricane property damage in a warming climate.

Michael Wehner of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and James Kossin of First Street Foundation and the University of Wisconsin-Madison co-authored a study suggesting the open-endedness of Category 5 of the Saffir-Sampson hurricane wind scale “becomes increasingly problematic for conveying wind risk in a warming world.”

According to the U.S. National Hurricane Center, Category 5 hurricanes have sustained winds of 252 km/h or higher, causing catastrophic damage. A high percentage of framed homes will be destroyed, with total roof failure and wall collapse. Fallen trees and power poles will isolate residential areas. Power outages will last for weeks to possibly months, and most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks or months.

In the study The growing inadequacy of an open-ended Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale in a warming world, Wehner and Kossin introduce a hypothetical Category 6, which would encompass storms with wind speeds greater than 309 km/h. They also propose a hypothetical modification of Category 5 for wind speeds of 252 km/h to 309 km/h in the study, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Our results are not meant to propose changes to this scale, but rather to raise awareness that the wind-hazard risk from storms presently designated as Category 5 has increased and will continue to increase under climate change,” Kossin wrote in a Berkeley Lab article.

The motivation was to reconsider how the open-endedness of the Saffir-Simpson Scale can “lead to underestimation of risk, and, in particular, how this underestimation becomes increasingly problematic in a warming world,” Wehner said.

According to Wehner, global warming has significantly increased surface ocean and air temperatures in regions where hurricanes, tropical cyclones and typhoons form and propagate, providing additional heat energy for storm intensification. When his team performed a historical data analysis of hurricanes from 1980 to 2021, they found five storms that would have been classified as Category 6, all of which occurred during the last nine years of record.

One was Typhoon Haiyan, one of the most powerful typhoons in history that devastated Southeast Asia (particularly the Philippines) with a maximum wind speed of 315 km/h in November 2013.

“But Haiyan does not appear to be an isolated case…” Wehner and Kossin wrote in the study. “A number of storms have already reached out hypothetical Category 6 wind speeds.”

Researchers also analyzed simulations to explore how warming climates would impact hurricane intensification. Models showed that with 2°C of global warming above pre-industrial levels, the risk of Category 6 storms increases by up to 50% near the Philippines and doubles in the Gulf of Mexico, the Berkeley Lab article said.

“Even under the relatively low global warming targets of the Paris Agreement, which seeks to limit global warming to just 1.5°C above preindustrial temperatures by the end of this century, the increased chances of Category 6 storms are substantial in these simulations,” said Wehner.

While hurricanes in Canada tend not to be as strong as in the U.S. and other parts of the world, there have been damaging ones. Hurricane Fiona cost the Canadian P&C industry more than $800 million in insured damage after making landfall in Atlantic Canada as a post-tropical storm on Sept. 24, 2022.

The storm brought torrential rainfall, large waves, storm surges, downed trees and widespread power outages. It remains the costliest extreme weather event in Atlantic Canada.

Feature image by iStock.com/FrankRamspott