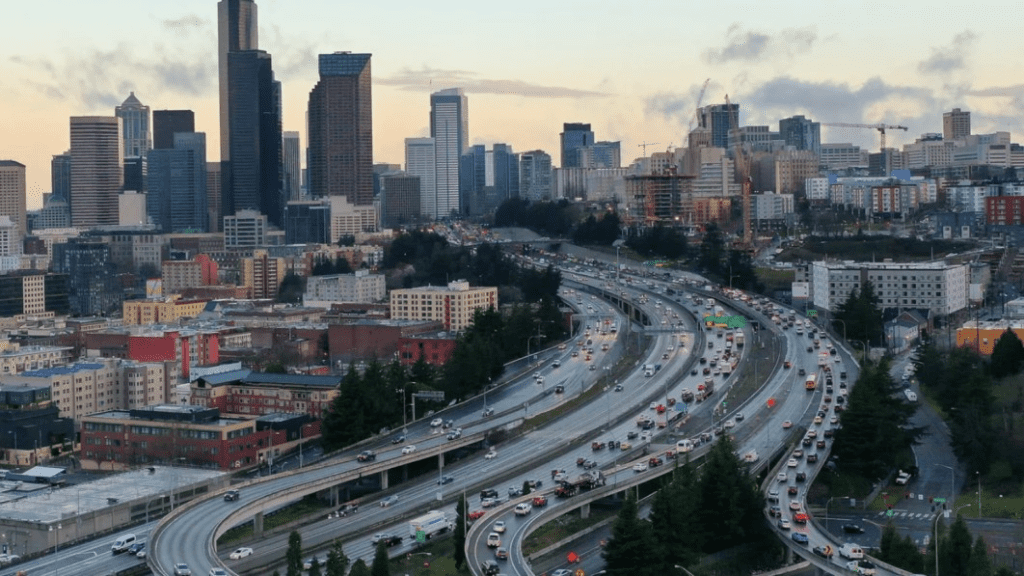

Exhaust pollution from highway traffic may affect blood pressure

It isn’t the sitting for hours in stopped highway traffic that’s most responsible for raising one’s blood pressure.

It’s the highway traffic’s fumes.

That’s among the findings of a new study from the University of Washington in Seattle. that exposure to roadway pollution — even brief exposure to the fumes and smoke; two hours in rush-hour traffic — can cause significant increases in blood pressure readings.

The measure of the BP rise is nearly 5 millimeters of mercury, according to the report. That’s a jump that would push someone with normal levels to elevated or from elevated levels to stage 1 hypertension.

“It’s a real, interesting, important number that if you think of millions of people having this exposure every day, that’s moving a lot of people from the normal to the high blood pressure range,” said Dr. Joel Kaufman. “That has a lot of impact on the risk of heart attacks and strokes.”

Dr. Kaufman, a university physician and professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at UW, led the team study, which was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

While the mental stresses of dealing with traffic may almost certainly exacerbate a person’s tension level, the study didn’t actively tackle that angle. Dr. Kaufman maintains that many people breathe in highway traffic fumes “while walking or biking or living, and historically these major roadways were cut right through low-income areas.”

The study doesn’t suggest solutions, except to say that improved filtration in vehicles, such as a HEPA filter, may help to catch harmful particles.

Initially in the process, researchers piped small amounts of diesel fumes into a closed room and found a bump in blood pressure among the roughly 40 participants.

Subsequently that took the experiment to the streets, using a Dodge Caravan equipped with filtration and monitors. They were driven through Seattle’s rush hour traffic for two hours on three different occasions. On two of the drives, the air was unfiltered; on one, it was filtered with HEPA devices. The participants did not know which was which.

Researchers found that, during the unfiltered drives, the blood pressure increases were similar to those seen in the lab, of just under 5 millimeters of mercury.

The study, funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and National Institutes of Health, was small, a limitation noted by the Annals of Internal Medicine. Just 13 participants returned usable data. However, Kaufman said he’s confident in the statistical significance of it.

Environmental inequities, often the result of highway placement, have received increased attention recently. As part of its massive infrastructure bill, the Biden administration set aside $1 billion for communities that were upended by highway construction and whose residents still breathe the toxic results.

Related video: