Cycling Infrastructure: will councils be bold and actually get the job done?

Back in July we looked at some of the active travel schemes the Government launched to encourage more people to get out of their car and use active forms of transport. Naturally, we hope most people will choose their bicycle. But, are councils really committed, and are they up to the job? With the surge in cycling interest during the pandemic, are the new lanes, quieter roads and fresh air here to stay? The Draft talks to sustainable travel researchers from the University of Salford and Glasgow Caledonian University.

Much has been made of temporary moves to encourage active travel and cycling, but has Covid-19 really changed the way councils approach transport?

Covid-19 has certainly meant that councils and transport providers have had to consider new challenges. They have had to think about the safety of transport staff, the need to enable and enforce social distancing on public transport and at interchanges, and keep vehicles clean, as well as how to cope with dwindling public transport revenues during lockdown.

That’s why proactive local authorities have responded to the popularity of walking and cycling during lockdown. We have seen people adopting active travel as a way of getting exercise outdoors and as a way of avoiding the risks associated with potentially overcrowded buses, trains and trams. Some councils have taken the opportunity to provide more space for walking and cycling, to make these options more attractive, and to enable people to travel actively while maintaining social distance from other road and pavement users.

There are other advantages too: cycling has long been recognised as a “climate friendly” way to travel, so the idea of “building back better” has given active travel policies new momentum [especially with Govenment plans to decarbonise transport by 2050].

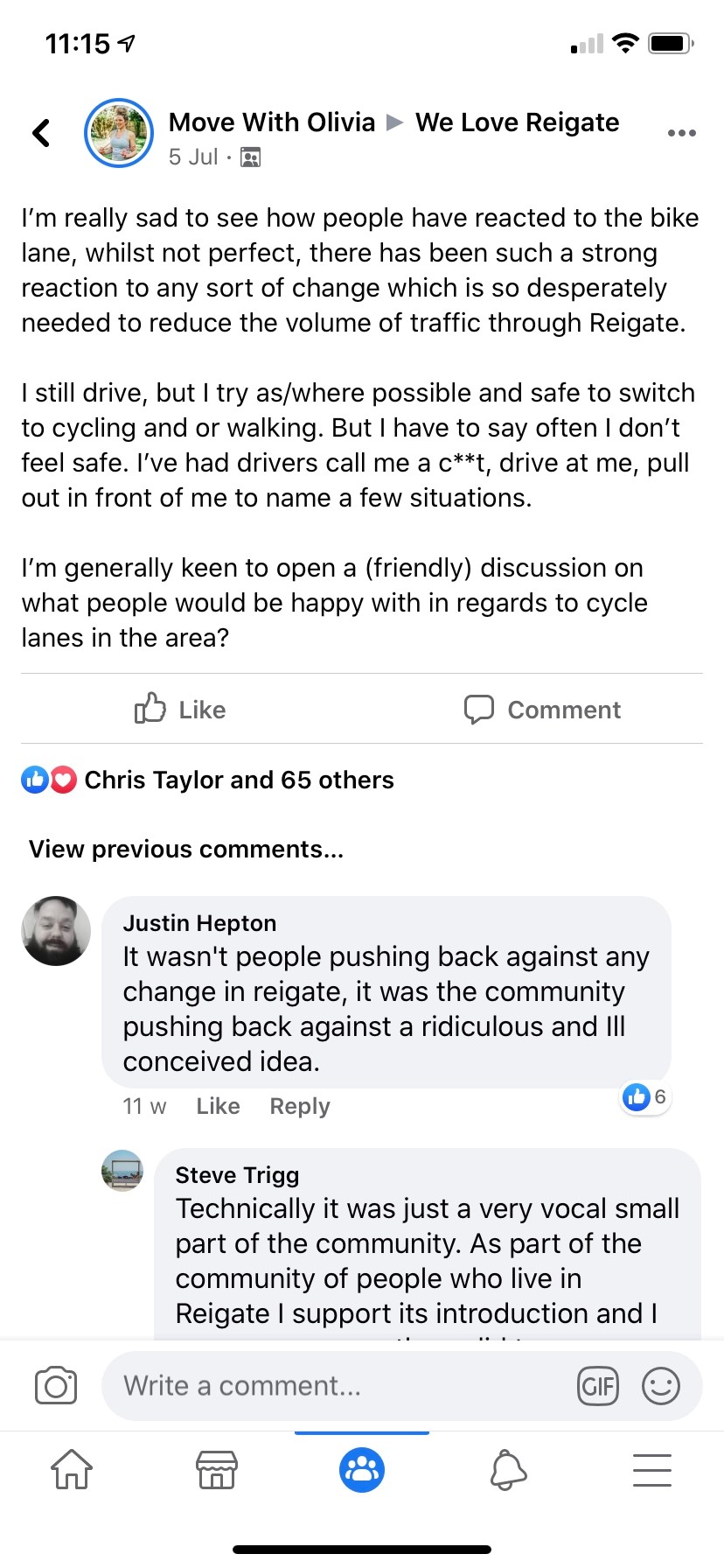

This has not come without its’ challenges though and a drive towards encouraging active transport, for example segregating traffic, has not been that well received in many areas.

What are some of the most innovative examples of pro-cycling planning you’ve seen during the pandemic so far?

In Greater Manchester we’ve seen some dedicated routes, including closure of part of one of Manchester’s busiest road, Deansgate, to general traffic, and lanes being coned off on some major arterial routes. These have been well received by those interested and involved in active travel but there are thousands of new cycling enthusiasts too.

As The Draft noted in May: Never has it felt safer to give cycling a go. “Traffic is light to non-existent and we’ve jumped towards the government’s vision of decarbonised transport.” There have been bike repair voucher schemes, proposals for GPs to prescribe cycling to help with people’s health and of course residential road changes.

Still, there have been criticisms about the ways they have been implemented in some cases. The segment of Deansgate, for example, has numerous planters and other obstacles designed to restrict traffic access but that also make access difficult for disabled people and people using non-standard cycles. Signage on other routes has been criticised – sometimes using ‘road closed’ signs that imply that it is closed to cycles too. One of us has had a near miss with a car driving left across the temporary lane not realising that it was a cycle route.

[In Reigate, Surrey, temporary cycling infrastructure (see image above) came upon against significant local pressure that led to it being removed. It’s a challenging time for local councils as they strive to keep everyone within their Borough happy. As always, however, there is a compromise and it’s finding that sweet point that will prove challenging for many councils.]

So, while these initiatives are definitely to be welcomed for their potential to boost active travel at a time when it’s greatly needed, there are clearly lessons to learn around design and implementation.

There are lots of polls showing more people want to leave their cars at home and cycle more, but is there really a big shift in behaviour going on?

We’ve known for a long time that promoting cycling is challenging. Although we can convince people of the benefits for journey time, health, personal finances and, of course, climate change and air quality, there are still barriers that make cycling appear difficult and potentially dangerous.

“The challenge will be keeping people cycling after traffic levels start growing again”

The biggest one remains the perception of risk in traffic and, related to that, confidence of cycling on busy roads. It’s easy to put off trying something new if it seems complicated and difficult. These new temporary elements of infrastructure are great and give people an opportunity to try out cycling. The challenge will be keeping people cycling after traffic levels start growing again and there is pressure on councils to remove the temporary infrastructure.

But research has consistently shown that what we really need to do is make that cycling infrastructure permanent and make it high quality, clearly separated from traffic, and well signposted. And we also need to enforce good driving standards, including speeding.

How can the temporary active travel changes become permanent ones?

There are regulatory challenges that can add delays and complications to making these active transport developments permanent, but the real challenge is political will.

We are already seeing pressure in Greater Manchester for the temporary infrastructure to be removed over concerns it is slowing down general traffic. The dilemma is that deterring people from cycling will add to that general traffic and the best solution is to find a way to encourage more people to be using that cycling infrastructure.

Councils now have the option to be bold, develop more infrastructure and promote it to make sure people know why it’s there and that it’s not just a temporary fix during the pandemic but a core part of creating a healthier society.

Dr Graeme Sherriff is coordinator at the Sustainable Housing and Urban Studies Unit (SHUSU), University of Salford.

Dr Nick Davies is lecturer in events and tourism at the Glasgow School for Business and Society, Glasgow Caledonian University.

Clare Cornes is innovation development manager at Greater Manchester Business Growth Hub/University of Salford.