USSR Sprinkled More Than 2,500 Nuclear Generators Across The Countryside

Ah, the USSR. It was a strange place with strange ideas. Ideas such as planting unprotected mini nuclear power sources into inhospitable and hard-to-reach areas. I mean, nothing should go wrong as long as the government always exists to maintain them, right?

Stainless Steel Is Way Better for Appliances, Not Cars

Welcome to the world of Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators or RTGs. It’s a piece of nuclear history I only recently learned about and thought I should bring this whole new horror to your attention as well. These things are just kind of rolling around famously stable Russia, and it seems like it should be a cause for concern.

RTGs are not nuclear reactors, nor are they “nuclear batteries.” Rather they work by converting the heat caused by radioactive decay into electricity. Due to the dangerous nature of the materials used however, countries like America only use RTGs in applications such as space exploration. Voyager, Cassini and New Horizons uses RTGs for power, as do the Mars rovers Perseverance and Curiosity. These probes however, use expensive plutonium-238 as their power sources and we launch them far the hell away from us.

The USSR though? Nah. It’s going to use super cheap, super radioactive Strontium-90 instead, though later, smaller RTGs used equally cheap Caesium-137 or Cerium-144. These three isotopes all have one thing in common; they’re all the products of spent nuclear fission. In other words, waste. The terrestrial Beta-M RTG is about 1.5 meters wide and 1.5 meters tall and weight about one metric ton, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency. The entire unit put out about between 1 and 1000 watts (quite the spread) and had a working life of 10 to 20 years.

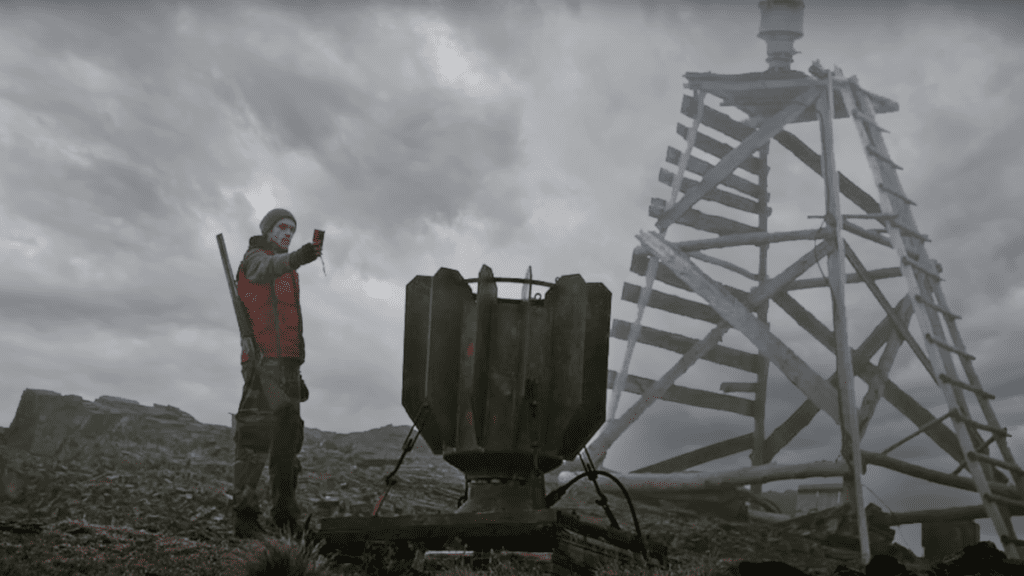

Originally built by the USSR’s Navy to power lighthouses and radio navigation beacons along Russia’s expansive arctic coastline, the RTGs provided power hundreds or even thousands of miles from civilization, occasionally completely unprotected and always unsupervised. They were occasionally secured by metal frames or sheds, but sometimes these lighthouses and radio beacons were set up on little more than rough structures hastily constructed out of nearby timber with the RTG stuck outside to face the harsh arctic elements. While the USSR provided regular rolling patrols to maintain the RTGs, that came to a screeching halt in 1991 when the Soviet Union fell. After that, there was no money to maintain the hard-to-reach RTGs, and they became victims of neglect and metal thieves.

After it proved useful for the Navy, the Soviets put the RTGs into service in other rough terrains. That’s how several ended up in the mountains of the former Soviet state of Georgia. Three residents from the village of Lia, Georgia, found a canister high up in the mountains. Since this strange material gave off heat, the three used it to stay warm overnight, but they woke up vomiting and dizzy. A week later, a military hospital diagnosed the three with radiation sickness. Two of the men would make it out with the help of dozens of skin grafts and months in the hospital. But the man who slept closest to the radioisotope source and handled it the most could not be saved.

Their arrival at the hospital launched a mad scramble from the international atomic community to find the orphan source of radiation. Footage of the clean-up crew both training for retrieval and actually snaring the Strontium-90 core shows just how dangerous RTGs are:

GEORGI~1 , Recovery of Orphan sources In Georgia,

That wasn’t the only incident involving RTGs however. In 2001, scrappers broke into a lighthouse on Kandalashka Bay and stole three radioisotope sources (all three were recovered and sent to Moscow). Three men in the mountains of Georgia were also exposed in 2002 after stumbling upon cores left out in the woods. In 2003, scrappers hurled a core into the Baltic Sea, where a team of experts retrieved it.

Today there are still hundreds of RTGs deployed along the Arctic shore of Russia, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency. The U.S. and EU partnered with Russia to clean up these orphan nuclear sources, and over 1,000 were reclaimed by officials for processing at the largest nuclear processing plant in the Russian federation “FSUE PA “Mayak.” However the program fell apart in 2014 following Russia’s invasion of Crimea and explosion from the G8. Russia then denied international help in cleaning up the RTGs. Though other countries do attempt to work with Russia to clean up the RTGs (Norway in particular is interested in clearing northeastern Russia) and some progress was made in 2019 towards allowing international help.