Boeing Engineers Set a New Record for Paper Plane Flight Distance

Screenshot: Missouri S&T

Dillon Ruble and Garrett Jensen, both engineers at Boeing, broke a record in December that had only a little to do with their day jobs: They broke the record for farthest flight by a paper aircraft, sending a sheet of paper 88.318 meters, or almost 290 feet.

Ruble and Jensen accomplished the feat with the help of Nathaniel Erickson; all three are cited on the Guiness World Records page, though Ruble is the one doing the throwing.

From the Boeing release:

Ruble and Jensen studied origami and aerodynamics for months, putting in 400 to 500 hours of creating different prototypes to try to design a plane that could fly higher and longer.

“For the Guinness World Records, we ended up going with A4-sized paper (dimensions of 210 x 297 mm) and went up to the maximum for weight, 100 grams per square meter,” Jensen said. “The heavier the paper, the greater the momentum when you go to throw it.”

It takes over 20 minutes to accurately fold the record-breaking paper airplane design.

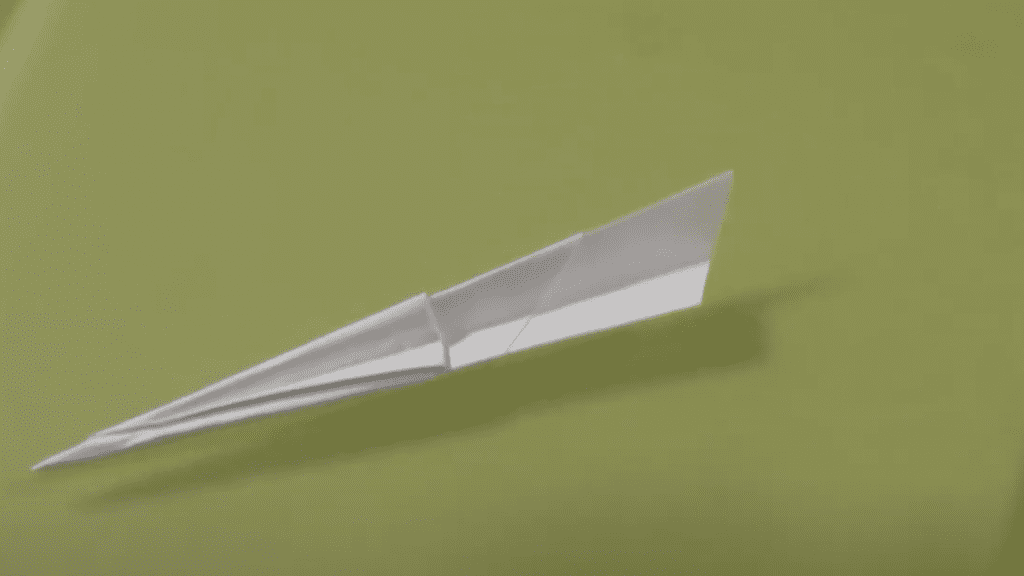

“Our design is a little different from your traditional fold in half, fold the two corners to the middle line down the middle. It’s pretty unique in that aspect. It’s definitely an unusual design,” Ruble said.

On the day of the attempt, they achieved the record on the third throw.

There is virtually no view of the plane that Ruble used in Boeing’s video, nor in their release, but below is a video from several months ago showing Ruble constructing a plane that looks to be similar to the one used in setting the world record.

How to fold a winning distance paper airplane: U.S. champion shares his secrets.

As you can see, the planes are meant to be more darts than traditional paper planes, and there is little, if any, gliding. Ruble’s tosses are all about brute strength and how far he can toss it, in addition to launch angle, which the team says optimally is around 40 degrees.

G/O Media may get a commission

“Once you’re aiming that high, you throw as hard as possible,” Jensen said. “It took simulations to figure that out. I didn’t think we could get useful data from a simulation on a paper airplane. Turns out, we could.”