VW's Bus Kept On Trucking, from the Age of Aquarius to the '90s

From the March 1992 issue of Car and Driver.

A palpable buzz of electricity was in the air of the pretty clapboard towns surrounding Richfield Coliseum south of Cleveland, even though the excitement—a three-night stand by those cosmic old fogeys, the Grateful Dead—was still two days away.

The buzz began with the first wave of wiggy old Volkswagen Buses that began appearing on the suburban landscape. Soon the local folks could be seen leaning forward over the steering wheels of their cars, squinting out at all the strange messages decorating the Buses. Look at that bumper sticker, Glenda!

“WE ALL LIVE DOWNSTREAM.”

“I NEED A MIRACLE.”

“MEAT STINKS.”

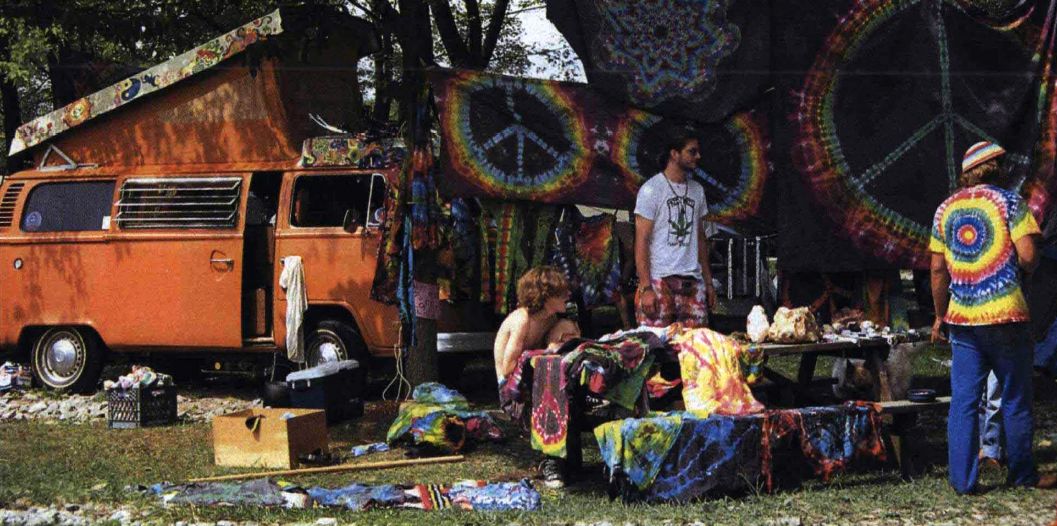

The “Deadheads” had arrived, the camp followers of the middle-aged rock group who will travel any distance to attend these mini-Woodstock gatherings of their musical tribe. They pulled their Buses and vans off road near busy intersections and set up shop, hanging up tie-dyes—sheets, shirts, hippie-style dresses, T-shirts, Grateful Dead posters and paraphernalia, rastafarian hair wraps—on clotheslines. Overnight, the landscape was transformed. It was as if a traveling Sixties roadshow of rootless hippies had come to town.

Brett UprichardCar and Driver

One supposes the locals appreciated the atmosphere of festival. There was a lot of grinning and shaking of their heads in local coffeeshops, but it was all good-natured. (In the Sixties, there would have been a local brick-throwing contingent, for those travelers brought with them strange ideas and mind-expanding chemicals.)

The night before the Cleveland concert, some Deadheads, suited up in their tie-dyed finery and sporting serious big hair and T-shirts with messages like “Eat, Drink and See Jerry,” appeared to drink beer and eat among the locals at the nearby Winking Lizard Tavern, one of those places that employ clean-cut college kids who have the exuberant look of having experienced farm work. You could feel the excitement; you could even smell the perfume of patchouli in the barroom.

The bartender, a strapping college-age youth, was asked if he was going to the concert. He grinned widely. “I was thinking of going,” he said, “but I’m kind of afraid it’d change my life.” A waitress his age heard that and laughed somewhat uneasily. She understood what he meant; strange ideas still have their allure, and there was always the possibility of moral defection, the temptation to dump tired old values. Who among these Nineties kids had not heard stories of the wicked Sixties, the sexual revolution, the Age of Aquarius?

Susana MillmanCar and Driver

So while the bartender laughed it off, maybe he considered the vague possibility of being overcome by a strange emotion to drop out, to buy a beat-up VW Bus for $500, to toss in a mattress, a hot plate, and a portable fridge, and to head off after the Grateful Dead. What a trip! Thousands of Deadheads do just that, and they manage to make a living in the process.

VW Buses and other provocative forms of weird transport were everywhere: lined up behind filling stations, parked in vacant lots and behind motels, and, most of all, jammed into a nearby state-park campground. Down in that park, the Age of Aquarius had returned.

The VW Bus has gone by many names—Microbus, Panel Van, Kombi, Crew Cab, Camper, Station Wagon, Vanagon—but it is the simplest van, the Bus, built between 1949 and ’79, that has been the vehicle of choice for those who have turned their backs on convention, or those who have wished to make personal statements about their values via their mode of transport.

Brett UprichardCar and Driver

The VW Bus, like the Beetle, has been “a negative status symbol” for most of its 42 years—plain as a brick, simple as a lawnmower, slow as glue, cheap to buy, cheap to run, and cheap to fix, it has hauled a lot of people (and surfboards) around in a style that disdains style. If you’re a Deadhead, it’s not just a vehicle—it’s home.

Something on the order of 6.7 million VW Buses have been built since 1949. Oddly enough, the idea for this simple “hauler” was not hatched in VW’s Wolfsburg plant in Germany, but in the head of an ambitious Dutchman named Ben Pon, who saw the potential of VW after the war and was to become an early exporter of its products (he personally brought the first Beetle to America).

Pon thought VW needed to offer more than just the Beetle, and with a simple sketch in a spiral notebook that is now a museum artifact at Wolfsburg, he drew a rendering of what he had in mind.

Conrad Neil of Manitoba sells posters out of his 1978 VW Bus.

Brett UprichardCar and Driver

Pon’s idea so captivated Heinz Nordhoff, the late head man at VW, that to launch the Bus in 1950 he had to cut back on production of the Beetle at a time when Volkswagen could not keep up with orders for its inexpensive car. It was called the “Type 2” (Type 1 being the Beetle). Nordhoff and Pon had guessed correctly—by the mid-fifties, VW had to build a plant in Hanover just to build the Type 2s. Eventually the homely hauler would be sold in 140 countries.

Imagine a 2300-pound van that promised to carry as many as nine people but was propelled—hardly the right word—by a 25-horsepower engine! By 1962, when the one-millionth “Bully” (named for its bulldog, workhorse stance) came off the line, its output had been increased to 34 hp and it finally got a synchronized transmission.

VW offered its Bus in countless configurations, with varying interior heights and bed plans and door arrangements. American buyers, who had to get up to speed on freeways, soon got a model with a 1.5-liter, 42-horsepower engine. (Still it was an adventure to be hit by a gust of wind in a VW Bus while crossing the Golden Gate Bridge.) The first major facelift came in 1967; the two-piece windshield was replaced by a single pane, its nose was flattened, and the doors, which had opened like those on a barn, were now sliding. The VW Bus craze in this country reached its peak in 1969, with a record 65,069 sold that year. More minor facelifts continued, and in 1972, a Bus arrived with a Porsche 914 engine. The following year, an automatic transmission was offered. In 1974, the Hanover plant was able to build an astounding 1200 Buses in a single day, and sales went over the four-million mark.

Emmet (I’m not a Deadhead”) Hollander.

Brett UprichardCar and Driver

The modern-day Bus, the Vanagon, appeared in 1979. It now had an all-wheel-drive model and a squared-off, all-business front. It was the best Bus ever made, but it had lost its goofy charm. Sales that had begun to slide in the seventies slipped even further in the eighties (5147 in 1989). The heyday of the VW Bus was over.

John Hollander, who goes by the name Emmett and is just 23, had parked his ’77 VW Bus behind a truck stop among a crazy quilt of Deadhead vehicles, including a couple of converted yellow school buses reminiscent of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters’ bus of Sixties psychedelic fame (“Positive Vibrations,” it announced). Kids roamed through the area, girls in muslin tie-dyes, and Jerry Garcia’s voice boomed forth from the open doors of cars. Hollander had driven all the way from Seattle, and he was digging around inside looking for something; the inside of his Bus looked like a twister had visited it recently. His hair was wild in rastafarian fashion, and he was slight of build, looking as if he hadn’t spent much time eating.

The Bus was painted a flat white, as if he’d done it with a paintbrush. The entire Bus was covered with hand prints in various bright colors.

Emmett is a budding entrepreneur learning the tie-dye ropes. It has not been all gravy. At a Denver concert of the Dead, ”the cops busted me for vending without a license. They took twenty shirts off me. I went home with $4.” It’s not easy being a Deadhead, although Emmett did not want to be described as one.

Brett UprichardCar and Driver

“What’s the deal with the hand prints?” he was asked.

”Well, I had a stencil of a hand, so… ” He thinks for a moment. What was his purpose? ” …so, I figured I’d put a black hand on one side, and, well, it just went from there.”

Like a lot of the independent thinking Deadheads, he gave me an answer that had the ring of Zen when I ask what it is he likes about his Bus, which has a rebuilt engine and cost him $2000.

“Uh, I kind of liked the idea of an air-cooled engine, you know?”

We wished him luck, and headed off for the park campground. A long gravel road led finally to a gated checkpoint, where we paid a $10 fee to get in. “Are there any Deadheads down there?” we asked a young woman wearing a khaki uniform and a Smokey the Bear hat. She rolled her eyes around in her head, like it was a question not worth answering.

Coming down the hill’s incline to a meadow where the tribe of Deadheads suddenly came into view, where Grateful Dead music filled the air, I was somehow reminded of Custer, and how he must have felt so momentarily strange coming upon the sight of an entire nation of Sioux camped at the Little Big Horn. It is reflexive upon seeing a sight like this to utter Christ’s first name, though not in vain. “Jesus.”

Brett UprichardCar and Driver

The first VW Bus that caught my eye belonged to Anthony Vanderford of Casper, Wyoming. Vanderford, who was 20, had been following the Dead since high-school graduation two and a half years ago. He had set up a table with all sorts of things for sale, and tie-dyed sheets were pinned to trees forming a canopy above his Bus.

The cheerful Vanderford invited me to look inside the Bus. Poking out from under a pile of bedding and clothing was a sleeping woman’s head. There was a sink and a stove and a refrigerator and running water, and a series of bunk beds.

“It’s a little home. It’s got everything you need,” he said proudly. Meanwhile, some potential customers poked over his goods. But these were Deadhead camp followers like himself, and I wondered out loud if it was possible to sell stuff to other Deadheads, who were in the same business.

He gave me a cosmic grin, like the whole thing was a mystery to him, too. “I know what you’re saying, but I’ve only been here a couple of hours and I’ve already made two hundred dollars!”

Brett UprichardCar and Driver

I came upon Conrad and Dan Neil, brothers from Manitoba, Canada. Conrad was selling exotic posters for $10 each. This was Dan’s third concert, but his brother has traveled to 30 of them.

Asked what it is about the Dead’s music that he found so alluring, Conrad had to think a moment. Finally he said, “The feel, man. It talks to you. It’s a natural high, and everybody’s calm. I like the calmness of it.”

An upholsterer by trade, Conrad had a fine ’78 Bus loaded with amenities. He summed up his affection for it: “It can sleep six and it’s great on gas. What else can I say? The guy I bought it from wanted $5000, but I got it for $3600. You can’t beat that.”

But in fact Jeff Johns of Pottstown, Pennsylvania, who was parked fifty feet away, beat that. His ’73 Bus cost him $475 just five months earlier. Okay, it wasn’t as nice as Conrad’s. Johns, 20, a cycle mechanic “on and off,” said be bought the Bus from a Czech who “buys them, fixes them up and sells them.” The Czech, it turned out, wasn’t setting any entrepreneurial records. “He bought this van for $400, and he was asking $550 for it. We told him our situation, which basically was we don’t have any money. So he sold it to us for $475.”

Angie Padgett, owner of the world’s prettiest freckles shows off the tie-dye work of boyfriend Steve Yatson.

Brett UprichardCar and Driver

Intrigued by an old ’72 Bus with a humorous protective vinyl bra strapped over its nose, I came around the back and ran into Angie Padgett, who would be, hands down, The Prettiest Freckled Girl in the World were there such a contest. She was posing for a picture when her boyfriend, Steve Yatson, showed up. They are both in their early twenties, and he’d given up the yuppie lifestyle to follow the Dead for awhile, learning tie-dying.

“I went from a Porsche 944 to this,” he said laughing, amused by his own change of lifestyle. “I paid $400 for this Bus, but I did tons of work on it.”

Angie said, “At some places, if you’ve got problems with your Bus, there are mechanics around who will work for beer.”

Yatson said, “l used to sell construction materials, and did very well. But you can make money here, too.” Pointing to a tiedyed sheet he’d made that was draped over his van, he said, “That sheet cost about $2 to make, and we sell it for $35.” It was clear that for Angie and Steve, this was a temporary lark. “I’m going to have to do the real-life thing again pretty soon.” Sometime soon he will be headed for college in San Jose, California.

Brett UprichardCar and Driver

We wandered around, and I was reminded of a conversation I had with Blair Jackson, a Dead historian from Berkeley, California, who puts out a periodical of Grateful Dead lore called The Golden Road. “The Volkswagen Bus is the cheap warhorse vehicle of the Seventies.

“There’s a whole iconography of the Dead and the VW.” I had to look that up. It means the images and pictures that become the symbols that describe a culture.

“The Dead has a tradition of taking traditional items from the culture and then twisting them—in a friendly way. Like [a depiction of] Calvin and Hobbes, only they’re smoking a bong or doing nitrous oxide. ” Just then I saw a Charlie Brown T-shirt, with Charlie’s head ballooned to watermelon size, making him “Cosmic Charlie.” Another shirt declared, “Bo Knows Jerry.” A Disney-like theme park reads, “Deadheadland.”

No one, including the Grateful Dead, now in their 26th year, can quite explain their popularity. Says leader Jerry Garcia: “Here we are, we’re getting into our fifties, and where are these people who keep coming to our shows coming from? What do they find fascinating about these middle-aged bastards playing basically the same thing we’ve always played? I mean, what do 17-year-olds find fascinating about this? …So what is it about the 1990s in America? There must be a dearth of fun out there in America. Or adventure. Maybe that’s it: maybe we’re just one of the last adventures in America. I don’t know.”

John Steinbach, Deadhead fashion king.

Brett UprichardCar and Driver

Blair Jackson says there’s a “sense of adventure” to it. “It’s rock ‘n’ roll with a bit of country-western. And blues. Actually, it’s like a jazz band—they never play the same set twice. They have such a large body of music—probably 110 to 120 songs at any given time. They played six shows in the Bay Area, and during all that, they repeated just one song—’Promised Land.'”

Whatever the case, in the first half of 1991, Dead concerts grossed $20 million. Their average take per show, according to Pollstar, a firm that reports on the music industry, was more than $1.1 million, or nearly twice that of the summer’s second biggest touring act, Guns n’ Roses. The Dead played nine nights in New York’s Madison Square Garden, three in Cleveland, and six at Boston Garden—and all of them were sold-out performances.

“We didn’t invent the Grateful Dead,” says Garcia. “The crowd invented the Grateful Dead. We were just in line to see what was going to happen.”

Like the popularity of the VW Bus, it defies explanation.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io