How migrants who move between Zimbabwe and South Africa access healthcare in border towns

Zimbabwe and South Africa share a 225 km common border. There is only one official border crossing, at Beitbridge. An estimated 15,000 migrants and refugees from Zimbabwe and other countries cross daily either through the official border post or at illegal crossing points. Migrants’ access to healthcare, particularly in the two towns along this border – Beitbridge and Musina – has come into sharp focus after the health minister of Limpopo province made disparaging remarks to a Zimbabwean woman seeking help at a South African hospital. Doctors Without Borders has been providing healthcare to displaced populations at Beitbridge for 22 years. The Conversation Africa spoke to Doctors Without Borders’ regional migration advisor Vinayak Bhardwaj about their research into migrants’ healthcare needs in the area.

What’s known about people crossing into South Africa?

In 2019 we did a survey to produce reliable evidence on the way migrants move and what the links are to their health outcomes.

In the survey we interviewed just over 1,600 migrants in the border towns of Beitbridge in Zimbabwe and Musina in South Africa.

For most migrants, Beitbridge was a transit site en route to South Africa. The main reasons they gave for leaving their countries of origin were to search for jobs and for better living conditions.

These economic motivations were coherent with the main difficulties many respondents faced in Zimbabwe as their last place of residence. Many respondents had travelled from countries further north and had spent some time in Zimbabwe en route to South Africa.

These difficulties were mainly unemployment, financial challenges and food insecurity. Although they were aware of the alarming levels of political persecution and civil unrest in Zimbabwe, none of the participants cited political-related factors as the main reasons for leaving Zimbabwe.

Men and women said they came searching for jobs. But the search for better living conditions was a more predominant reason to leave the country for men than for women. Motivations involving family, such as a family gathering or starting a new family, were more common among female respondents.

The number of migrants at the Beitbridge border post and their reasons for leaving their countries of origin.

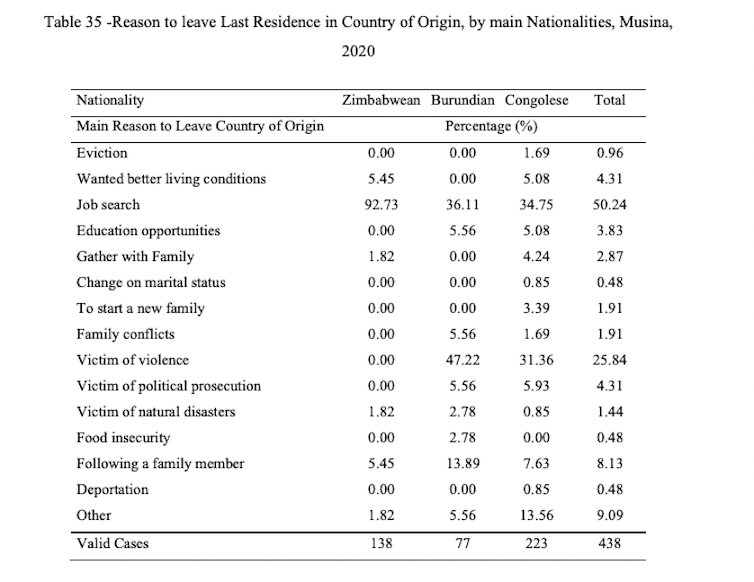

The number of migrants in Musina and the reasons for leaving their countries of origin.

Our survey was initiated before the COVID pandemic and the data collection was concluded and published just as the pandemic began. Some of these findings may therefore be different now.

What are the biggest insights about their health needs?

For a long time there has been insufficient information about migrants’ medical needs in this area.

In Beitbridge, the health needs often related to chronic or infectious diseases such as hypertension and malaria. There was also high HIV prevalence among women. And there was a significant need for mental health services.

Our results showed that Central Africans coming from countries such as Burundi and Democratic Republic of Congo were particularly hampered from accessing medical care, primarily due to language barriers. Because their primary language was French, accessing care in English was difficult.

The survey also showed that sexual violence was a reality for migrants. An estimated 36% of single female Malawian migrants residing at a safe house in Beitbridge said they had experienced sexual violence.

In Musina, there was evidence of high levels of sexual violence and abuse among male migrants. There was also a significant need for mental health services. Burundian migrants and asylum seekers in particular reported poor mental health indicators.

What facilities are available?

On the Zimbabwean side, there is one hospital and four government clinics: Beitbridge Hospital, and Dulivadzimu, Nottingham, Shashe and Tshikwarakwara council clinics, which offer primary health services.

These facilities are all in the town of Beitbridge. The clinics are strategically located in the Beitbridge urban district. The Beitbridge district hospital caters for both local and mobile populations.

These facilities are geared towards providing services around chronic conditions. Their capabilities to provide mental health and sexual and reproductive health services are more limited. At the Dulivadzimu council clinic, Doctors Without Borders supports the facility with human resources, filling in gaps for the pharmacy, and providing laboratory support.

In addition to these facilities, Doctors Without Borders has set up a small mobile clinic at the Beitbridge Reception Centre, which provides primary healthcare to Zimbabweans who are deported and to people moving through to South Africa.

In the town of Musina, there are three state-run facilties: Musina Hospital, and Nancefield and Musina clinics.

Recently a quick needs assessment by Doctors Without Borders in the area showed inappropriate water and sanitation facilities at the site, as well as difficulties in accessing healthcare in the public clinics and hospitals.

On the back of these insights Doctors Without Borders established an emergency project in the so-called men’s shelter in Musina town.

The organisation also established the “Musina model of care” – a strategy which targets agricultural workers based at distant farms. The idea was to create a mobile approach with core minimum services, including antiretroviral treatment and tuberculosis treatment for those who could not access clinics.

Having achieved successful rates of treatment continuation, the activities have been handed over to the South African authorities.

What did you learn about the scale of migration in the area?

Historically, the flow of migration in southern Africa is towards South Africa, as shown by the International Office for Migration’s flow trends data.

But consolidated data has not been consistently collected for the last two years, due to the COVID pandemic. The International Office for Migration, which tracks this information closely, reported that during the pandemic (2020-2021), over 200,000 Zimbabwean migrants returned to Zimbabwe mostly because of the lack of economic opportunities in South Africa during the pandemic.

The closure of the Beitbridge border for several months (on the Zimbabwe side) during the pandemic, as well as the further restrictions on legal movement, such as the requirement to provide a negative PCR test, further reduced legal migration. This affected irregular migration in ways that haven’t been tracked yet.

More recent data is available on a month-to-month basis, documenting the flow across the Beitbridge border. But this has not yet been analysed to assess whether the scale of migration has returned to pre-pandemic levels.